National Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research Obstructed

Ruling Halts Federal Funding of Embryonic Stem Cell Research

Last week, a ruling by federal Judge Royce C. Lamberth left many human embryonic stem cell (hESC) researchers not only scrambling for funding and concerned about the future of their own research, but also concerned for the future of the whole field in this country. Lamberth, chief judge of the Federal District Court for the District of Columbia, ruled that federal money cannot be used to fund hESC research.

Although earlier this week the Justice Department moved to appeal Lamberth’s ruling, it may be some time before the situation is sorted out, during which valuable, life-saving research will be delayed. To understand this controversial ruling, both how it came about and its implications moving forward, it’s important to take a look at the history, biologically and politically, of hESCs in the U.S.

How Are hESCs Generated? In 1998, a group led by Dr. James Thomson, who holds faculty appointments at the University of Wisconsin and the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), isolated embryonic stem cell from humans for the first time. Specifically, these cells are isolated from four- or five-day-old embryos called “blastocysts.”

These blastocysts are not yet implanted into a uterus, and contain approximately 150 cells.

Where did these blastocysts come from? Thomson’s group used blastocysts from in vitro fertilization (IVF) clinics with full donor consent. Since then, additional hESC lines have been created (a “line” consists of all the cells grown from one given blastocyst). This was often done using blastocysts from IVF clinics that would otherwise be discarded (often because the blastocysts were damaged and would not properly develop into a human, although IVF generates a large number of excess healthy blastocysts that go unused as well). Since IVF has become such a popular practice (now responsible for 1 in 100 births in the U.S.), there are now more than half a million frozen blastocysts in the U.S. alone; there does not appear to be a shortage.

Policies Under Bush: In 2001, President George W. Bush adopted restrictive human embryonic stem cell polices. Under these policies, research done with only 21 of the original hESC lines would be eligible for federal funding, while work done with other, newly generated hESC lines would receive no federal funding (although that research could still receive private funding).

Changes Brought by Obama: President Barack Obama’s administration changed Bush’s human embryonic stem cell policies. In March 2009, Obama made it possible for researchers to receive federal funding for research on more than 75 different hESC lines. In essence, the new rules stated that a hESC line could be federally funded as long as the blastocyst used was obtained with full consent of the donors and the blastocyst would have otherwise been discarded (after being harvested for use in an IVF clinic). However, federal funding could still not be used to generate new hESC lines.

The Lawsuit Obama’s new policy quickly provoked a lawsuit, led by Nightlight Christian Adoptions and two adult-stem-cell researchers, Dr. James L. Sherley (a former MIT researcher who notoriously went on a hunger strike after being denied tenure) and Dr. Theresa Deisher (president and founder of Sound Choice Pharmaceutical Institute). The plaintiffs claimed that the new policy violated the Dickey-Wicker Amendment, established in 1996, which states that federal money cannot be used for “research in which a human embryo or embryos are destroyed, discarded or knowingly subjected to risk of injury or death.” The Obama administration policy was intended to obey this amendment, as it did not allow for federal funding in the generation of hESCs, but only for their downstream use.

How Valid Is the Lawsuit? To determine how valid the objection against funding of human embryonic stem cell research is because of its use of human embryos, it’s important to understand two key aspects of hESCs’ unique biology and derivation.

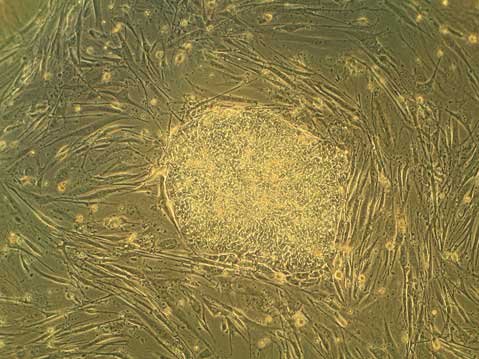

First, while adult stem cells (stem cells isolated from a variety of adult tissues) are limited in their lifespan, hESCs can be grown and expanded indefinitely, potentially creating an infinite number of hESCs from a single human embryo. Consequently, most research facilities that use hESCs do not isolate blastocysts and create hESC lines themselves, but purchase the cell lines from a large cell-banking facility or a collaborator.

Second, researchers have shown that it is possible to generate hESC lines without damaging the embryo.

Not only is it possible to create hESC lines without destroying a human embryo, and not only does each blastocyst provides a potentially infinite number of cells for research, but most researchers who work with these human embryonic stem cell lines never encounter donated human embryos, just the lines generated from them. However, this has not stopped Drs. Sherley and Deisher from pursuing their suit.

If at First You Don’t Succeed, Appeal, Appeal Again: Last year, the suit was dismissed by a ruling that the plaintiffs would not be materially affected by a change in the policy. However, the suit went to the Court of Appeals, which reversed the dismissal when it ruled that Sherley and Deisher were harmed by Obama’s policy; as they only worked with adult stem cells, theoretically they would have to deal with increased federal funding competition (due to an increase in hESC research). In these economically tight times, one wonders how many other researchers might resort to prosecuting away their competition for funding sources. In any case, Sherley and Deisher became the only plaintiffs remaining on the lawsuit.

Chief Judge Lamberth (who was appointed in 1987 by President Ronald Reagan) ruled to block Obama’s hESC policy on August 23, 2010, asserting that federal funding could not be used in hESC research because the research “necessarily depends upon the destruction of a human embryo.” Lamberth stated, “If one step or ‘piece of research’ of an E.S.C. research project results in the destruction of an embryo, the entire project is precluded from receiving federal funding.”

Lamberth claimed that his ruling was simply a return to the “status quo,” but many feel that the judgment is unclear, and are understandably quite concerned about the implications of the ruling; it now appears that no hESC research can be federally funded at all, creating a policy even more restrictive than that established by the Bush administration in 2001.

The ruling has shocked the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and researchers alike, disrupting research in hESC laboratories across the country. The NIH quickly declared that the ruling would not affect grants that have already been paid this year, but renewals and grants currently being reviewed will be postponed. This includes $54 million that the NIH was to award to several hESC projects across the country during the month of September; the ruling prevents these projects from receiving this essential funding for medical research.

On Tuesday, August 31, the Obama administration moved to block Lamberth’s ruling, but it will take time before the judicial process comes to a resolution. Unfortunately, it is not easy or efficient to simply put hESC research on hold; these cells are delicate, and require time to reinitiate growth once they have been stopped.

Why Are hESCs So Promising? One of the amazing, and quite useful, attributes of human embryonic stem cells is that they are pluripotent, meaning they have the potential to become virtually any cell in the adult human body. Consequently, they hold great potential in the medical field for treating a wide variety of diseases; researchers can make the hESCs become a desired cell type and use these in transplants or other cellular therapies. (Adult stem cells, on the other hand, are much more limited in their potential; they can usually only become a few different cell types, and consequently are not applicable for treating as wide a variety of diseases as hESCs are.)

Researchers have shown promising results on the ability of human embryonic stem cells to aid in treatment of spinal cord injuries, blindness, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, muscular dystrophy, heart disease, and more. Research in some of these areas is being done within just a few hours’ drive of Santa Barbara.

Dr. Hans Keirstead, associate professor of anatomy and neurobiology and codirector of the Sue and Bill Gross Stem Cell Center at the University of California, Irvine, spoke in Santa Barbara last June about a treatment he developed that became the first-ever FDA-approved clinical trial using human embryonic stem cells. Dr. Keristead created oligodendrocytes from hESCs, and showed that an injection of these cells into rats with spinal cord injuries could significantly improve their motor functions. (Oligodendrocytes protect the neurons that are injured during spinal cord injuries.) Dr. Keirstead and collaborators at the biopharmaceutical company Geron will be proceeding with clinical trials of patients with acute spinal cord injury using these hESC-derived cells.

Several groups have used retinal cells derived from human embryonic stem cells to treat different forms of blindness. Advanced Cell Technology, a Santa Monica-based biotechnology company, is seeking FDA approval to use such derived cells to treat Stargardt’s macular dystrophy, after studies in rats showed that the cells could restore vision. Similarly, researchers at UCSB, led by Dr. Dennis Clegg, are studying how hESC-derived retinal cells can be used to treat age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Alternative Funding: Luckily, many hESC laboratories have alternative, private funding that is not affected by Lamberth’s ruling. The most significant untouched funder of hESC research is likely the Califorrnia Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM), which in 2004 was given $3 billion (through California’s voter-approved Proposition 71) to spend on stem cell work. In October 2009, researchers at UCSB received $2.5 million of this funding for use with hESCs in treating AMD—which is just one of many potential applications of hESCs.

For more on Judge Lamberth’s ruling against Obama’s hESC policies and hESCs in general, see the New York Times article “U.S. Judge Rules Against Obama’s Stem Cell Policy,” the Los Angeles Times article “Ruling a blow to stem cell research,” National Public Radio’s article “Obama Appeals Stem Cell Ruling; Some Work to Stop,” The Forum on Science, Ethics, and Policy’s article “Court Ruling Prevents Funding of Embryonic Stem Cell Research,” and previous “Biology Bytes” articles including “Showtime for Stem Cells”.

Biology Bytes author Teisha Rowland is a science writer, blogger at All Things Stem Cell, and graduate student in molecular, cellular, and developmental biology at UCSB, where she studies stem cells. Send any ideas for future columns to her at science@independent.com.