Christ the Activist

New Book Traces Jesus of Nazareth’s Life, from Possible Slave to Social-Justice Militant

Like anyone raised Catholic, Jesus became a force in my life before I was old enough to invite him in, the cool waters of baptism washing over my infant head just a few months after birth. Then came my first communion in 2nd grade (dressed up, walked straight, didn’t drop candle), my first confession in 4th (stressful queue, minor sins, prayers to say), and a dizzying array of school lessons (God’s always watching!) and forced church services until I was nearly 17 years old.

Though predominantly Irish-Catholic on both sides as far back as anyone could tell, my family wasn’t particularly devout — in retrospect, my immediate clan’s parish involvement looks like required means to the ends of a good education — so there wasn’t really much hell to pay when I decided against confirmation. My teenage mind was processing so much science and history and verifiable facts that the whole Jesus story seemed pretty outrageous to me. The central message of being a kind person resonated — and still does — but to tell a congregation that I actually believed in so much hard-to-fathom dogma struck me as hypocritical. And in that boat I remain, believing that Jesus’s message of indiscriminate compassion must be repeated often to a recurrently ruthless society but wondering what all the ritual fuss is about. And as far as “God” goes, the serendipitous marvels and unexplained mysteries of life satisfy my spiritual needs just fine.

But my inquisitive mind has never strayed far from wondering about the circumstances surrounding Jesus the man, from his everyday life to how he sparked a belief system that shaped the world as we know it to shattering suggestions that he never existed at all. Lucky for me, such ponderings have also lured more prepared scholars into answering those questions, including Jean-Pierre Isbouts, a professor at Santa Barbara’s Fielding Graduate University whose new tome, In the Footsteps of Jesus: A Chronicle of His Life and the Origins of Christianity, was released last month by National Geographic Books.

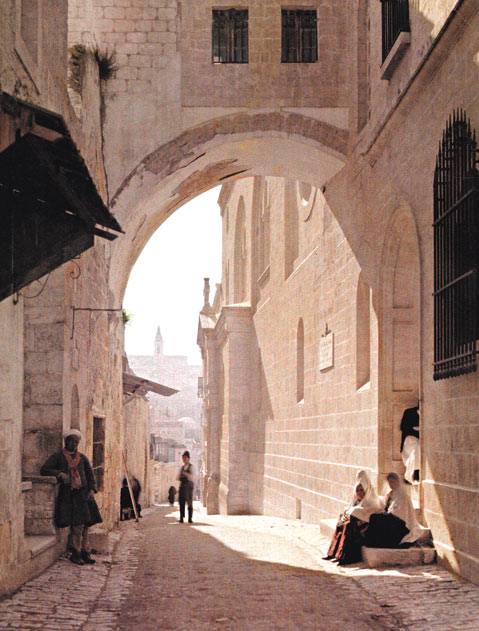

Drawing on an extensive collection of multidisciplinary research, from ancient histories to biblical archeology to Greco-Roman economics, Isbouts paints a vivid portrait of the world as Jesus knew it, so scene-setting that Jesus doesn’t even appear as a topic until more than 100 pages into the 300-page book. Among other theories, Isbouts posits that Jesus was born near Nazareth, not Bethlehem; that he was a construction worker who toiled on new Roman cities rather than a carpenter; that he valued women as equal to men; and, perhaps most critically, that his ministry was as much about political and social activism as it was about religious belief. And in that latter discovery, that Jesus’s role was about bringing economic freedom and everyday justice to a land deeply divided between the rich and the poor, there’s much for our contemporary world to learn in this Christmas season, even lapsed Catholics like me.

To get a better sense of Isbouts’s ideas, we spoke for about an hour over the phone earlier this month. What follows is a condensed and streamlined version of our wide-ranging conversation.

As a scholar, do you believe that the Gospels can be treated as trustworthy historic documents? Some claim Jesus was entirely fabricated. If I had a dime every time I hear that! What do you expect? A Facebook page perhaps? A group photo with Jesus and the Apostles? It’s absurd. You might as well say, “Did Plato exist? Did Socrates exist?” These are ancient times. What evidence would there be of an ancient figure other than literary references that emerged after his death?

We know that Jesus was the son of a family of Galilean farmers. They were peasants; they were illiterate. We know that Jesus could read, but nowhere do we see evidence that he could also write. Those are two different skills in antiquity. It is perhaps the great tragedy of Jesus that his ministry was so unbelievably short. My personal estimation is about 18 months. The man has barely enough time to write down his vision of the new kingdom even if he wanted to.

What do you think it was about Jesus’s message that resonated so much with the people then? The official religion of the Mediterranean basin was being eviscerated by the imperial approach. Smart people like Cicero didn’t really believe that there was a god for this and a god for that and that, if you wanted a baby, you were supposed to pray here, and if you wanted a good harvest, you’d go pray there. They realized it was something not all that credible.

But the Roman-Greco religion that was imposed on all these territories had become a ludicrous farce because it made any emperor that died into a god. Many of the people under the Roman occupation began seeing this. The second reason is that you cannot look at Jesus without looking at the widening gap between rich and poor.

Now comes Paul. Without Paul, there wouldn’t be any Christianity. There’s no question about it. Here comes Paul into the European continent talking about this Asian person named Jesus who says that God isn’t going to be upset if you don’t sacrifice, but that God is a passionate father who cares about you whether you are a slave, a free man, an aristocrat, or a constable, and, more important, a man or a woman.

The kicker of that message is that if you lived a moral life and you believed in Jesus and through him this incredible benevolence, you would find a reward in heaven. That package was unprecedented.

There were other religious products for sale, but none of them matched the idea of a monotheistic god who was passionately involved with you. Even though you suffered today, your reward would be great in heaven, provided you lived a moral life. That went around the Roman Empire like wildfire.

What do you think Jesus intended his impact to be? From his words, it’s clear that Jesus was inspired to his ministry because of the great socioeconomic injustices going on around him, and the solution for him was to create a new paradigm of a compassionate society.

In the 1970s, when we were protesting the Vietnam War, we didn’t jump on barricades and say, “In Samuel 2 …” Political activism and religious activism were completely separate. But that was not the case in ancient times, and you see that throughout the history of the prophets. They articulate their activism in the vocabulary of the Torah because that’s the only vocabulary they know. Their religious and political activism were fused.

I think Jesus’s ministry was initially absolutely focused on the Jewish population. He does not go to any cities in the Decapolis, which is the region’s biggest urban center — they were non-Jewish. He doesn’t go to Tiberius, which is non-Jewish. He never goes to Sepphoris, which was by and large a Greco-Roman city. He keeps his message to small townships and villages, which were predominantly observant Jewish. So initially, his message was only for the lost sheep of Israel. That was a really big task, tremendous task.

Had a message of compassion never come out before? Religions had always been very much aligned with the power structure. The principal deities, even going back to Amon-Ra in Egypt, were co-opted by the ruling elite and were really an extension of their political aspirations. In Mesopotamia, there is a symbiosis between the gods and the needs of the everyday farmer, but the relationship is contrarian — those deities were very fickle, and they may just throw you a famine because they feel like it. You were constantly stressed out.

The idea that there could be a single god, that itself isn’t unique. But that God is a benign force with whom you can communicate as a child to a father? The Torah refers to Israel as God’s children, but Jesus translated the concept into intimate terms of Abba, something like Daddy or Poppy. The Jewish God is such a remote figure that you can’t refer to his name directly. But Jesus said, “No, call him Daddy.”

Do you think that Jesus himself wanted to be deified? There is no question that when Paul brought Jesus’s message beyond Asia Minor, it would have been very difficult for the audience to consider him the prophet, the communicator of God, if he did not have divine properties himself. This was Europe, not Asia. The message has to be Europeanized to make it plausible for someone in Athens or Rome.

But Jesus himself, being of the Jewish religion, wouldn’t necessarily disagree. King David was called the son of God, too. And even being very close to God in the Jewish sense could imply a very close relationship as if between a father and son.

The Christology that has evolved since crucifixion has translated that into biological terms. There we must all reach into our hearts as Christians to determine how important that is to us. To me, Jesus is my personal savior, and I consider him to be the metaphorical son of God. That’s me talking as a believer, not a historian. Do I need biological evidence to make that tangible? Personally, I do not.

As a historian, Jesus talked very much about our relationship to God not as an exclusive proposition. We are all children of God, he said. If I am a child of God, so are you. The prayer we all say every Sunday, it starts with “Our Father,” and that’s how I would like to answer that question. The greatest accomplishment of Jesus is that he showed a way for a very intimate communication with God.

Do you hope that this book has any on-the-ground effects? With Footsteps, I really aimed for my children, who are in their early to late twenties. The whole Christology that has been built around Jesus is not very appealing to many young people today, which is why most people are very secular and consider going to church a drag.

What I tried to do in this book is strip away this patina, these Christological layers, and probe for the real and living human being underneath. I think if young people really knew Jesus as I know him, as a social and political activist, they would find him a lot more cool than they do right now.

Short of such big questions, the book would work well as a travel guide to the region. Are there any plans for a pocket-sized travel edition? I’ve been approached by a tour operator, and I am going to be leading several tours next year using the book as guide. So I look forward to taking people to show them not just the sites but the meaning of the sites. It gives me a thrill.

In addition to writing, you have one of the more expansive résumés I’ve ever read. You’ve directed Charlton Heston, fostered the multimedia revolution, become an expert on fine art, developed encyclopedias, written novels, taught PhD students, and so on. Where do you find the time? Very careful time management. Every day, I wake up, decide what the schedule is going to be, and I try to stick to it like glue. Calls to my students I do in the morning, and then I write in the very late afternoon. And working at Fielding in Santa Barbara is really great. Since we’re a doctoral program, I can spend a lot of time with my students and guide them on their dissertations, but it still leaves me time to do my own research. That’s a great blessing.

With your résumé, it seems that you could teach anywhere. Why Fielding? What attracts me to Fielding is the idea of graduate education. I don’t have the time to be standing in front of the classroom every day like you would in undergraduate education. Instead, you have time to focus on a small group of students that you are mentoring, that you really try to help achieve their goals. And at the same time, you can do your own research. The wonderful thing about Fielding is that we try to actively involve our students in our research.

4•1•1

Jean-Pierre Isbouts will lecture about In the Footsteps of Jesus on January 18, 2013, at 7 p.m. at Fess Parker’s DoubleTree Resort in an event hosted by Fielding Graduate University. See jpisbouts.org.