Sisquoc River Scramble

A Gnarly Father-Son Bildung-Backpack

Name of hike: Sisquoc River father-son shuttle backpack

Mileage: 34-mile backpack down the Sisquoc and up Manzana Creek from Manzana Schoolhouse Camp

Suggested time: 6 days/5 nights strenuous backpacking, no layover days, river-walking the Sisquoc amid riparian splendor. (The 120-mile trip on Hwy. 101 North to Hwy. 166, and across to Rock Front Ranch, includes 33 rough miles on Sierra Madre Ridge Rd. to McPherson Camp. It’s about a three-hour drive from Santa Barbara’s Westside.)

There is a weird pleasure that comes when you manage to invent a unique backpacking trip into Santa Barbara’s gorgeous backcountry. East of Santa Barbara town, north of Los Angeles, and far from any urban centers.

The Sisquoc River shuttle backpack I managed to pull off a few years ago with my son (“the McCaslin Boy” or “the Boy” for the purposes of this column) qualifies as a much different route than the usual, and it created a peak moment between son and father in the wild. Our 34 backpacking miles along two local rivers in the San Rafael Wilderness indelibly marks the Boy’s deepening education (Bildung) in natural history and in life.

The sheer magnitude of our dazzling local backcountry bewitches the imagination and calls for us to march out there and enjoy this great American wilderness. The San Rafael Wilderness’s 240,000 acres adjoin part of the 60,000-acre Dick Smith Wilderness, which abuts in some places the smaller paradise of the Matilija Wilderness. These and two other federal wilderness areas are further encompassed by the 2,000,000 acres of the fabulous Los Padres National Forest.

It’s almost 71 miles as the crow flies from Santa Barbara to Bakersfield, and most of that area is federally owned and surrounded by the Los Padres. About 15,000 acres of the Los Padres have oil leases or mineral production, but most of this ginormous territory is “virgin land.” The five federal wildernesses near us in Santa Barbara are especially well-protected: According to the historic 1964 Wilderness Act, nothing motorized is allowed in these wild regions: no chain saws, no motorcycles or bikes, no ATVs. There are, in fact, no roads at all. The worthy goal of this important legislation is to protect forever areas “where the earth and community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

Happily for Santa Barbarans, the spectacular San Rafael Wilderness is near the heart of the Los Padres, and the wild and scenic Sisquoc River forms the gushing core of the glorious “San Raf.”

Few humans backpack into the Sisquoc Canyon. Craig Carey’s Santa Barbara and Ventura hiking guide (reviewed in my last column) wisely omits my novel route, and he never recommends the wicked Jackson Trail.

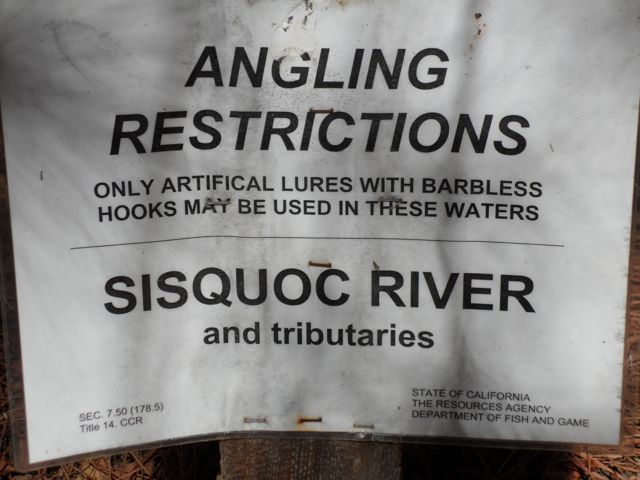

Dennis Gagnon describes his aptly-named Great Circle Wilderness Loop as hardy backpacking in “an area especially alive with color and movement in March and April. You will experience the deep and remote Sisquoc Canyon, the unspoiled heart of the wilderness area.” The magnificent Sisquoc River is the last truly “wild” stream in southern California, and boasts its own native trout population (no fishing allowed). I’d accomplished and enjoyed this 49-mile loop backpack five times, so I believed the navigation part of this backcountry adventure with my son would be easy. We wouldn’t do the full loop, but would cover about 34 miles of it. I knew we’d also drink the pure water straight out of the sacred source, Mother Momoy’s sacred Sisquoc watercourse, both unfiltered and unparalleled. (Always use your water filter.)

This sort of shuttle backpack requires two vehicles, of course. Conning someone into driving their car over 120 miles out into the godforsaken barrens of the Cuyama Valley to drop us would be nearly impossible. However, my teaching colleague Chris Caretto, “Mr. C” as students call him, and his spouse wanted an easy backpack to introduce their infant son to wilder parts of the earth. Two-year old Cyrus would feel his Bildung expand, too. We concocted a fairly complex driving plan, with Mr. C and family riding with the Boy and me out to the Cuyama in our F150 truck, and then along the dreaded and bumpy 33-mile Sierra Madre Ridge fire road to McPherson Camp. There is a barred gate, and a corral, and this is the end of the public access road. We backpacked together as a group of five along the easy six miles of the closed fire road continuation, down to Painted Rock Camp on the Montgomery Potrero, where we had a very pleasant overnight and a bit of a celebration.

The more strenuous backpacking began the next day for the Boy and me. The Carettos would enjoy another day at Painted Rock, then hike back along the fire road to the truck and drive back around to Nira Camp, to camp there and meet us five days hence.

The Boy and I set off in high spirits from Painted Rock Camp at 4,600 feet, to some of the rolling and beautiful grassy meadow (you officially enter the San Raf here), and then begin heading down the notoriously poor Jackson Trail. Several guides mentioned how sketchy and treacherous this steep 5-mile descent to Sycamore Camp (elevation 2,000 ft.) is, and it did not disappoint.

As the 12-year-old McCaslin Boy trudged along the top of the Jackson Trail, he could see straight down the 2,600 feet into the deep V of the Sisquoc Canyon. The 26 pounds of gear he toted in his backpack, equaling about a quarter of his own 104-pound weight, felt pretty heavy. He and his father had done other long backpacks, but as part of his backcountry Bildung, his father promised this one would be even more beautiful and intense.

Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor writes eloquently about the losses suffered by our modern, “buffered” selves. Among them are a loss awareness of one’s natural surroundings. In A Secular Age (2007), Taylor writes, “We need to have our petty circle of life broken open. The membrane of self-absorption…” needs to be ruptured. Along with great art, the experience of true wilderness can achieve this beneficial breakthrough.

Taylor contends that “the importance of the wilderness in the period after 1700 [and today] is not that it offers us an alternative way of life…Rather, it communicates or imparts something to us which awakens a power in us of living better where we are.” Nature and the wilderness then aren’t simply places of refuge, they are higher zones where we can encounter “vagueness, terror, sublimity, strength, and beauty” as 19th Century editor and politician Joel Tyler Headley wrote, in the The Adirondack, or Life in the Woods.

During several decades as a middle school teacher, I have observed many wonderful children, but some of them have been so sequestered from nature and natural experiences, it’s possible they have lost something. As face-to-screen communication and the idolatry of connectivity dominate the land, I fear for kids who seldom experience nature in the raw. They miss how intense and challenging Gaia is, dark and scary Shiva, how beautiful, uplifting, and, above all, unpredictable.

Taylor writes movingly of the “sublimity and the moral meaning of wilderness [and] the felt inadequacies of modern anthropocentrism, and the need to recover contact with a greater force.” In the 21st Century, that force does not have to be “god,” but it could be the overwhelming power and force of the Sisquoc River in full spring spate after a particularly heavy series of winter rains.

The Boy and I were often silent, each conversing with an inner spirit. The German Bildungsroman (growing-up novel) like Hesse’s Demianor, or The Man Without Qualities by Robert Musil, did not feature challenges greater than those my 12-year-old weathered on this grueling backpack in white water season. We did not exactly go “off trail” as we struggled to descend the 2,500 steep feet down to Sycamore Camp: The extremely steep path simply disappeared and we were on our own. The Jackson Trail was gone. Nor were we technically “lost,” since far below we could see the bend in the gushing river where the bench for lovely Sycamore Camp stood. We went down one dizzying descent only for this animal trail to stop at a small but impassible cliff. The Boy was crying, and I was clambering mightily on all fours, barely managing to get back up to a higher spot so we could assay another attempt.

After a horrible day, hours of discouragement, we finally flopped into enchanting Sycamore Camp, bedecked with the eponymous sycamores and three separate fire rings. Ominously, the roar of the Sisquoc River’s white water had reached us high up on the supposed Jackson Trail, and once in camp, as we gratefully fell into our tent, I could hear the rumble of large boulders actually moving below the river’s churning surface. Too tired to worry about it, we were ecstatic to rest, cook a pleasant supper, and fall asleep after humming a few songs.

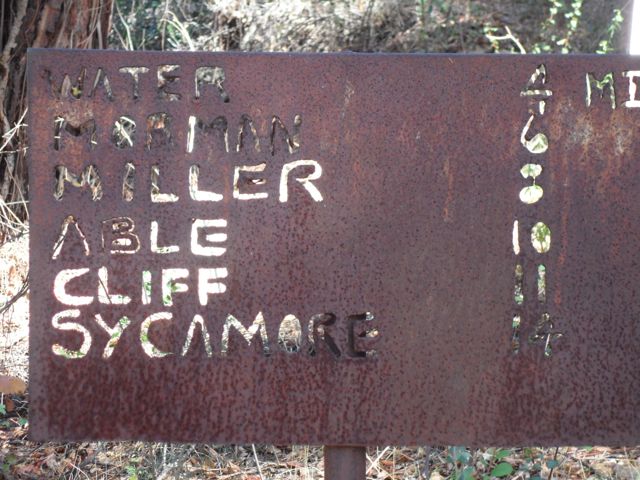

The next day, Day Three, witnessed the commencement of several days of tedious yet exhilarating river-walking in breathtaking Sisquoc Canyon. We would pass through and overnight at these U.S. Forest Service camps: 3.3 miles to Abel Camp with its plethora of gnarly ticks; then 4.6 miles the next day to our beloved Mormon Camp; another 6.1 miles through Water Canyon to the confluence of the Sisquoc River and Manzana Creek, at Manzana Schoolhouse Camp; and then on the final, sixth, day, about 9 miles up the verdant Manzana to our friends with the truck at Nira Camp.

The three-day descent from Sycamore to Manzana Schoolhouse featured scores and scores of river crossings, and in the area between Sycamore and Abel it was not only quite deep, but the water was very cold, and the skies were gray, with a savage early spring wind cutting through our wet clothing. At 175 lbs. plus over-heavy backpack, I could bull my way through these crossings using my special bamboo pole, but even so I fell over a couple of times – but without damage except for a fright and a dunking. The Boy was so light that I had a concern about him floating downstream (!) with his pack on, so for the first two river days I would most laboriously follow this procedure at every deep crossing: I go over, drop pack, cross back, and then cross with my Boy, me wearing his pack on one arm and holding him up with the other. It became terribly exhausting and both of us were quite cold and wet for hours until we got to the next camp.

Abel is a barren camp and showed no signs of recent use. We were overjoyed to think no one had been there since the previous fall. Some people call Abel a horse camp, but horses wouldn’t have been able to get down the Jackson or down from South Fork. A trail horse would have refused the many deep crossings we endured. Some of them were above my mid-chest, but the pace of the flow was nothing like I’ve witnessed in the eastern Sierra.

Mormon Camp is a terrific site which we enjoyed greatly, and by this point, 8 miles down from Sycamore, the river flow had diminished significantly so the crossings were fairly easy although we would have wet boots all day. During the night at Mormon, a pack of coyotes came right near our camp and began howling just outside the thin fabric of our tiny tent. After telling the Boy not to leave the tent without me, I just rolled over and went back to sleep with their ululating howls filling my ears.

Our fifth day was again replete with many Sisquoc River crossings as we trudged to well-known Manzana Schoolhouse with its many tables, and where we switched over to water-crossing beautiful Manzana Creek. I have described the 9-mile final day back up to Nira Camp in a previous column, as the return from the Hurricane Deck West backpack.

Father and son achieved solitude together in rough nature (we never saw another hiker!), our shared time broadened the relationship, and we laughed often over the evening campfire. We recognized the incisive Taoist insight from the Tao Te Ching that things started out well when humans were merged with nature, but then dropped into an abyss when “culture” was invented. We endured the exciting Sisquoc whitewater adventure together, and deepened our love.