The Electric Coral Acid Test

Scientists Study Deep-Sea 'Poster Child'

Last Wednesday afternoon, a group of scientists and a handful of lucky onlookers crowded around a heap of computer monitors onboard a NOAA research vessel in between Santa Cruz and Anacapa islands. In the middle of this scrum were two men controlling a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) 500 feet beneath the boat’s hull.

Later in the day, an oceanographer named Peter Etnoyer would ruminate on the fact that when he was in college, researchers still believed that the deep sea consisted of dead zones devoid of life; however, the ROV’s electrical eyes revealed an ecosystem teeming with fish, crustaceans, and the organism that nobody knew actually existed in the Santa Barbara Channel until recently: coral.

Everyone held their breath as they watched the ROV clamp onto a pink gorgonian coral bush, more commonly known as a sea fan, and deposit it onto the submersible’s “front porch.” Exhales. Applause. Soon after, scientists and their assistants were slicing and dicing the specimen so it could be preserved for examination. The abiding question is how deep-sea corals are impacted by ocean acidification.

Corals, the second-most simple animals (the first being sponges), form hard exoskeletons from calcium carbonate, and they tend to thrive in conditions where the water is saturated with such minerals. However, when oceans absorb carbon dioxide — which they have been doing increasingly since the Industrial Revolution, becoming on average 30 percent more acidic — the change in chemistry reduces the number of carbonate ions.

Marine scientists use the saturation of one particular calcium carbonate called aragonite to discuss acidification. The “aragonite saturation horizon” marks the depth below which corals cannot form their exoskeletons. As acidification increases, the depth of the horizon becomes shallower. In the California Current system, it was between 300 and 350 meters in the pre-industrial era, before 1750. It is roughly now 150 meters, and by some predictions, it will be 50 meters by 2050.

Aside from their beauty, corals provide habitat for both invertebrates and fish. “Corals are to fishes as trees are to birds,” said Etnoyer. They support entire ecosystems. They also hold pharmaceutical potential, Etnoyer explained, are crucial to biodiversity, and are an “indicator species,” manifesting earlier than other species’ impacts to the ocean environment.

The scientists were particularly interested in Lophelia pertusa, a white-colored stony coral species. Lophelia, said Etnoyer, is a “poster child” because it exists all over the world. The Lophelia in the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary seem to be healthier than the scientists predicted. They guess this might have to do with the richness of food sources in the area, or it may be due to the fact that this portion of the Pacific is naturally highly acidic due to upwelling, so perhaps the corals had already become inured to such conditions.

Because of their inaccessibility, deep-sea corals are still quite mysterious creatures. “Eighty percent of the data we collect is imagery,” said Etnoyer. He surmises that he was drawn to studying deep-sea corals because of his first career working on Hollywood movie sets. “It’s all cameras, it’s all light,” he said of the submersible vehicles that marine scientists depend on.

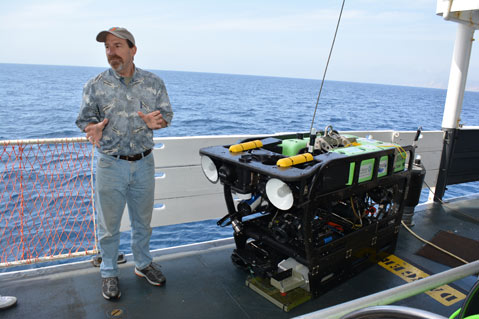

The ROV on the Bell M. Shimada was designed by a nongovernmental organization called Marine Applied Research and Exploration (MARE). Executive Director Dirk Rosen, one of the ROV operators on the ship, is based in San Francisco, but his motivation for founding the nonprofit is a Santa Barbara story.

A graduate of UCSB’s engineering program, Rosen had been diving in the channel since 1976 when he attended early meetings on the formation of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) within the Channel Islands sanctuary. Distressed at the “demise” of sea life in the area, he asked scientists what they most needed, and their response was “deepwater data.” He launched MARE in 2003, the same year the MPA regulations went into effect, and his machines have been gathering data up and down the West Coast ever since.

At the end of the day, everybody was pleased. The mission was a success. They’d collected all the coral samples they could hope for, and after 30-knot winds the night before, the waters were calm.