Botanic Garden Turns 90

An Evolving Horticultural Legacy Since 1926

It’s May 1 at Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, and more than 500 people are on hand to celebrate the Mission Canyon property’s 90th anniversary (which technically was March 16). Among leafy species labeled Leymus condensatus (canyon prince giant wild rye), Rhus integrifolia (lemonade berry), and various strains of drought-tolerant manzanita, guests stroll through the “water-wise” garden while others inhale the calming notes Bob Sedivy blows from his shakuhachi inside the Japanese tea house. Near the Campbell Bridge, gigantic boulders loom in a veritable jungle of lush greens as lovers gaze at tranquil scenes from benches punctuating the trails. The landscape magically blends scientific research with public visitation, says the garden’s development director Nina Dunbar, who explains, “These gardens are kind of like zoos.”

Only seven years after the Jesusita Fire, it’s hard to believe much of this had been scorched. Aside from an old wood bridge that’s been replaced by another wooden bridge, there’s no evidence of any change or scarring from that notorious blaze. The redwoods survived; the surrounding foliage regenerated and thrived.

For many dyed-in-the-wool Santa Barbarans, these hallowed horticultural grounds may be as easy to take for granted as the nearby Mission or Stearns Wharf. Yet when the forward-thinking, pioneering property opened in 1926 as a research park, it became the first botanical garden in the country devoted to native plants (arranged in ecologic communities rather than individual specimens), which also made it ground zero for early studies of sustainability, including water conservation.

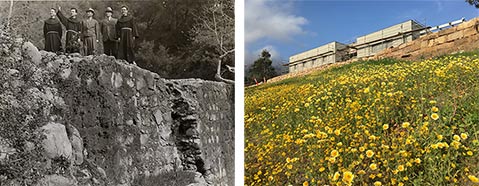

back to when dams — visited here by unnamed padres, Maunsell Van Rensselaer, and General William Lassiter — were built by the Chumash across

Mission Creek. Progress continues in the form of the John C. Pritzlaff Conservation Center (above right), opening in July.

The brainchild of inaugural director and plant ecologist Frederic E. Clements of the Carnegie Institution for Science, botanist Ervanna Bowen Bissell, and her husband, Elmer J. Bissell (who succeeded Clements), the institution began as a 13-acre parcel called Blaksley Botanic Garden, gifted by philanthropist Anna Dorinda Blaksley Bliss. By the 1950s, it had expanded to 78 acres, including five miles of trails along both sides of Mission Canyon Road. The garden’s founding fathers and mothers were wisely focused on ecological issues and a shifting environment, but those concerns are even more pressing today. “It is a critical time for conservation of native plants,” said the garden’s communications director Rebecca Mordini. “The garden’s role is more important than ever with climate change.”

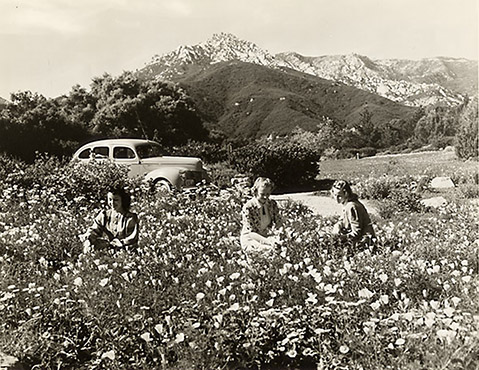

Enmeshed in all of that history is famed landscape artist Lockwood de Forest III, who worked on the garden from 1926-1949, save for two years during World War II — but even while enlisted, de Forest advised Bissell by correspondence. “It was really Lockwood de Forest who liked the naturalistic versus the linear landscaping,” said Dunbar.

A man ahead of his time, de Forrest was focused on California’s endemic treasures rather than exotic species. “That’s what the garden was: to exhibit and foster native plants,” said Kellam de Forest, Lockwood’s eldest son. “That was part of the rationale. It was not designed as a conventional botanic garden.” He also wasn’t afraid to point out what doesn’t work in this region. “In the 1920s, he wrote about lawns and how they didn’t belong in Southern California,” said Kellam de Forest, who is 89 years old.

In 1938, when landscape architect Beatrix Farrand joined the garden’s advisory committee, tensions arose, so Kellam de Forest calls the Meadow entrance “a compromise” for his father, explaining, “It was a little more formal than he would’ve liked, but the naturalistic meadow remains, as does the view.” That said, Lockwood de Forest was proud of his achievements, even though he never lived to see them to completion — he died from pneumonia in 1949.

and the Blaksley Library (below, built in 1942) survived multiple conflagrations in recent

years, including the Jesusita Fire and a political mess over the Vital Mission Plan.

But the work went on. Lutah Maria Riggs designed the offices adjoined to each side of the garden’s library by 1961 and also conceived a research wing built in 1964. An enlarged unit for horticultural research and propagation was established in 1973 and, a year later, the John Pitman–designed herbarium opened — and is today the region’s largest scientific collection of preserved Central Coast plant specimens (about 140,000).

Not every moment of the Botanic Garden’s history has been a bed of roses. In 2009, there was the Jesusita Fire, financial woes from the recession, massive layoffs, a volunteer strike, and a large public uproar over changes proposed in a “Vital Mission Plan.” But the plan was retooled, perceived bad guys moved on, and the new director, Steve Windhager, came on to usher in a new era.

Today, Windhager is managing a $14 million “Seed the Future” campaign, which is already benefiting the original Meadow, the Wooded Dell around the historic Campbell Bench, an Island Section featuring deciduous plants, and the Centennial Maze, commemorating the Garden Club of Santa Barbara’s 100th anniversary. The new children’s maze offers a labyrinth of coyote brush occasionally dead-ending into “Gnome Homes,” miniature houses inside which small, handwritten “Be Back Later!” notes from absent little residents await kids opening its tiny doors.

Opening in July is Seed the Future’s cornerstone: the John C. Pritzlaff Conservation Center, an 11,500-square-foot facility with an herbarium housing more than 150,000 plant specimens. “Think of it as a library with a live catalogue of genetic material,” said Dunbar. Staffers seem excited about the new building, which will be fire-safe, include wet and dry labs for molecular research, and, according to Mordini, feature “a big open display where tourists can observe the scientists at work.”

That’s just one more reason for the garden’s 55,000 annual visitors to keep coming back.

See sbbg.org

Editor’s Note: This story has been corrected to reflect that the Pritzlaff center holds an herbarium, not an arboretum.