The Thomas Fire Strikes Back

Beast Still Breathes Despite Saturday’s Epic Firefight in the Montecito Foothills

It was a day few in Santa Barbara will ever forget. Early in the morning on Saturday, December 16, as howling winds developed overnight, the Thomas Fire roared through the canyons above Summerland and Montecito, cresting ridges toward Westmont College, Parma Park, and dozens of small neighborhoods tucked away along narrow mountain roads.

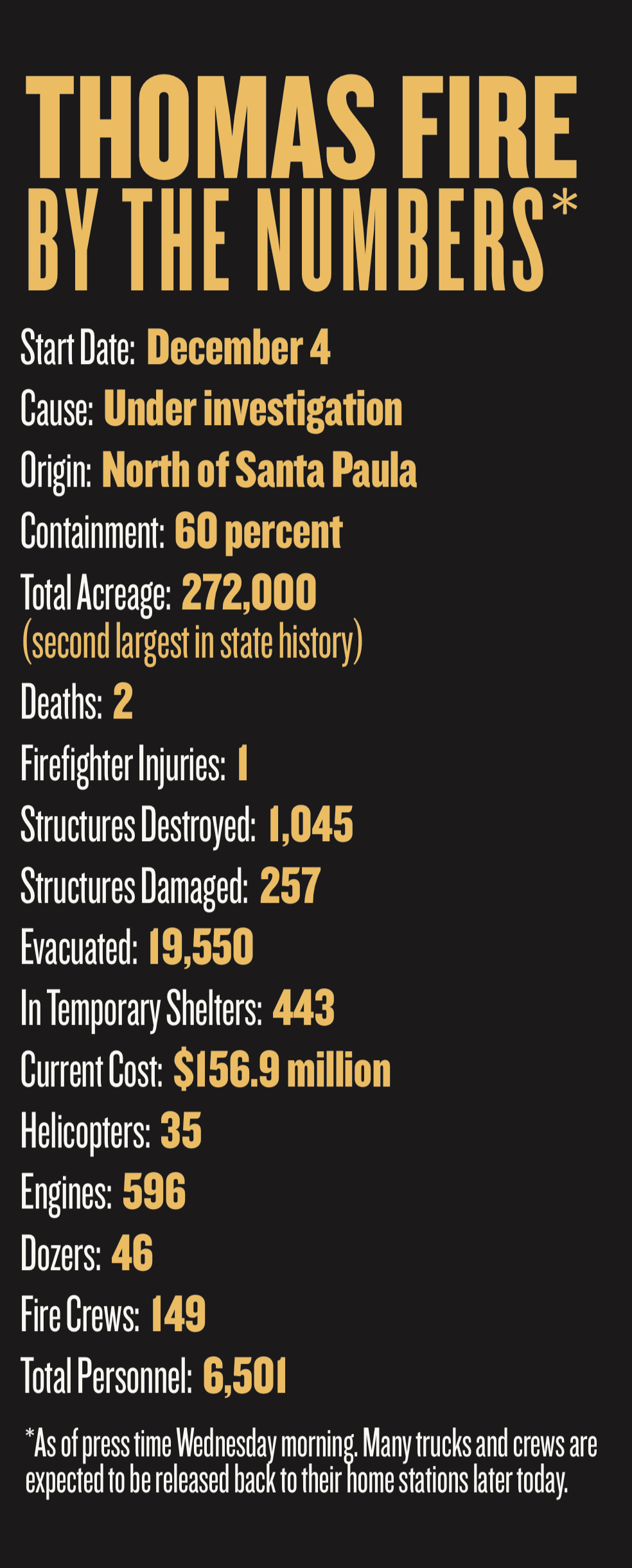

By then, the Thomas Fire was already 12 days old, sparking to life around 6:20 p.m. on Monday, December 4, in Ventura County, near Thomas Aquinas College. By then, the out-of-control wildfire had already destroyed hundreds of Ventura homes and forced thousands to evacuate. By then, a class-action lawsuit had already been filed, alleging its cause was connected to a Southern California Edison project. By then, it had already jumped Highway 33 and the Ventura River and burned right down to Highway 101 at Faria Beach Park. By then, the Thomas Fire had already killed two: 70-year-old Virginia Pesola, who died in a car crash while evacuating near Santa Paula; and 32-year-old firefighter Cory Iverson, who died working the inferno’s southeastern edge, outside Fillmore.

Needless to say, Santa Barbara firefighters saw this thing coming. As the fire jumped Highway 150 and landed in the backcountry north of Carpinteria, hand crews and dozers were opening up long-established fuel breaks from the county line westward. Then they got a big break. While relative humidity remained at dangerously low, single-digit levels, weather forecasters predicted four days of calm wind, a welcome reprieve after more than a week straight of unseasonal Santa Anas.

At that point, according to Santa Barbara County Fire Battalion Chief Chris Childers, the plan was to funnel the western edge of the fire toward the area burned by the Tea Fire, in 2008, and the nearby Jesusita Fire, a year later, as the northwest edge burned toward the 10-year-old scar left by the Zaca Fire, deep in the backcountry. Based on decades of fire-behavior analysis, incident commanders knew that the relatively young chaparral in those regions — despite seven years of historic drought — would serve to slow the fire.

They got to work, and after four days of cutting firebreaks, laying hose, dropping retardant, and generally taking over entire neighborhoods north of Highway 192 throughout the 93108 area code, thousands of firefighting personnel braced against the coming windstorm of December 16. They were as ready as they could possibly be.

Even so, reflected Santa Barbara County Fire Department Captain Dave Zaniboni, when the winds arrived, “conditions were as bad as it gets.” The wind blew stronger than predicted, running steady in the 30-40 mph range, with gusts surpassing 60. “Honestly, I thought it was going to burn to the beach,” Zaniboni said Tuesday. “I was absolutely shocked when I didn’t see any fire below [Highway] 192, and a lot of the really seasoned guys were saying the same thing.” Of the estimated 1,300 structures immediately threatened by the fire that day, 10 homes were destroyed and 10 damaged.

In terms of technique, Childers said, “We didn’t want [our teams] sitting next to a potentially dangerous structure, waiting for the fire to show up.” When an approaching fire is too big and hot to handle, that approach can result in melted fire trucks and worse — loss of life. “We wanted them ‘fire-following,’” Childers explained. “We wanted them to go to a place that was relatively safe — a temporary refuge that’s not beneath any heavy fuels — and once the fire hits the area, to drive back in there, to follow it in, and — if it’s safe — to try to save the homes by putting out fires on both sides of the driveway and around the property.

“That’s what we did,” he added. “It was a true firestorm up there that day, and we had no reportable injuries.”

The next day, Sunday, December 17, marked collective but cautious relief among the greater firefighting force. The fierce winds had vanished. The smoky skies had cleared. People outside removed their face masks for the first time in days and attempted to return to some semblance of normal life. Things were looking up as teams assumed an offensive approach, tracking down and extinguishing hotspots and reinforcing defense lines in anticipation of another blow of northerly winds predicted for December 20. (Visit independent.com for an update on that).

Late Sunday afternoon, the Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office started opening up evacuated neighborhoods in Carpinteria. Summerland, and Montecito, and parts of Santa Barbara soon followed. Monday and Tuesday arrived with more favorable weather as the unfortunate homeowners returned to survey their ravaged properties, personally escorted by Montecito Fire Protection District Chief Chip Hickman.

Officials now estimate the Thomas Fire will be totally contained by January 7, 2018. In the meantime, the fire’s capacity to drain a bank account couldn’t have come at a worse time, exacerbating the holiday cash crunch as businesses struggle to offload inventories stocked up in anticipation of robust Christmas sales and families struggling with unanticipated escapes from smoke and flame, kids at home instead of at school, and workplace shutdowns.

Economic hits combined with evacuation scrambles left thousands without basic shelter and food, according to Judith Smith-Meyer, a communications manager with the Foodbank of Santa Barbara County. Last week alone, the nonprofit handed out shelf-stable grains and legumes, fresh fruit, bread, and milk to about 1,000 people per day. Recipients represented a range of Santa Barbara citizenry, from evacuated families with no time to clear out the cupboards to entire workforces in limbo — landscapers, construction workers, retail salespeople, and others living paycheck to paycheck in a halting economy right before Christmas. Explained Smith-Meyer, “The fear of that loss of income is going to go on for quite some time.”