‘BlacKkKlansman’ Touches Raw Nerves of Race Politics

Spike Lee’s Film Shows How Threat of Violence as Traumatic as Violence Itself

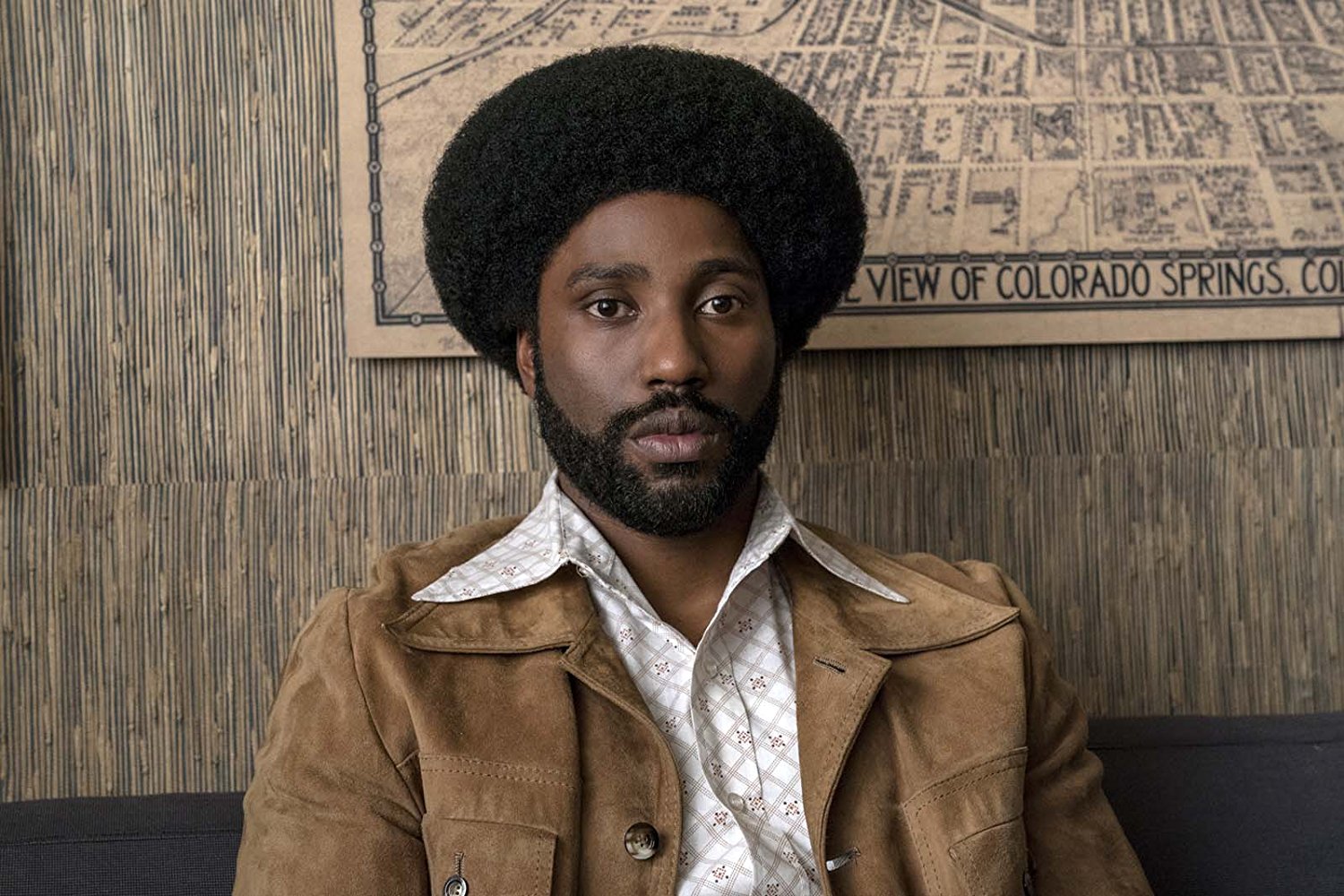

Take a moment to observe moviegoers trying to order their tickets for BlacKkKlansman (“Um, two for the Lee movie”), and you’ll get a sense of how well Spike Lee’s new film touches the raw nerves of current American race politics. A collaboration with Jordan Peele, director of Get Out (2017), and starring John David Washington, BlacKkKlansman is based on the true story of the first African American police officer in the Colorado Springs Police Department, who manages to infiltrate the Ku Klux Klan and stop a terror campaign. Coordinated for release on the anniversary weekend of the notorious Unite the Right riots in Charlottesville, it’s hard to imagine a more timely film than this one. Or, for that matter, a more disquieting depiction of the violence of racist language and images, and how the threat of violence can be as traumatic as violence itself.

Set in 1972, BlacKkKlansman’s plot follows rookie detective Ron Stallworth (Washington), who, trying to prove his chops as the only black cop on the force in Colorado Springs, demonstrates his self-proclaimed ability to code-switch between “white” and “jive” to dial up the “Organization” — that is, the KKK. To everyone’s surprise, including his own, Ron manages not just to pass but to impress the local Klan leader as a sufficiently bigoted potential member. When the Klansmen want to meet in person, however, the operation requires a white undercover avatar. Ron remains the telephone voice, but his white partner Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver) steps in as the physical Ron, although the difference in their voices and his concealed Jewish background attracts the skepticism of the Klansmen (Ryan Eggold and Jasper Pääkkönen). Considerable hazing and peril ensue.

Flip is a fictional addition to the film, but his presence illustrates a sometimes overlooked development in the history of the U.S. Civil Rights movement: the breakdown in what had been a perceived shared struggle between American blacks and Jews, as Jewish people became accepted increasingly as white. Although Flip is not a practicing Jew, a key plot thread involves him realizing that he has spent his life passing amid white supremacy. It is amid this crisis of identity that Zimmerman-Stallworth’s double cover within the KKK begins to collapse. This escalates when the Jewish-Klansman and the Black-Klansman must be present simultaneously at a banquet attended by none-other than David Duke (Topher Grace), where the Klansmen toast to — what else? — “America First,” one of this film’s many historically accurate jabs at the origins of the Trump administration’s rhetoric.

The film’s intellectual core lies in the character Patrice (Laura Harrier), president of Colorado College’s Black Student Union and Ron’s love interest. Fashioned as a dead-ringer for activist Angela Davis — Ron even calls her Angela Davis in one scene — her many conversations with Ron, whose undercover status she only learns on a delay, offer a crash course in American race relations. These conversations are occasionally didactic, and that is the point: Patrice’s power as a character is that she never, ever lets the logic of injustice off the hook. Patrice also catalyzes what may be the film’s most moving sequence, aside from the ending. When Ron begins his undercover work, he originally is sent to monitor potential unrest in the black community. He attends a speech by Black Panther Kwame Ture (Corey Hawkins), whom Patrice has invited to speak at the college. As Ture gives an inspired speech about black power and the coming revolution, the camera focuses on the faces of the audience members, whose galvanized expressions, floating in the darkness, speak volumes.

The casting choice of Washington as Ron is a brilliant one, and not only for Washington’s deadpan-until-explosive performance. Washington’s presence directly ties BlacKkKlansman to Lee’s earlier historical biopic Malcolm X (1992), which starred the actor’s A-list father Denzel. Topher Grace captures the disturbing boyishness of David Duke as naturally as if he were reviving Eric from That ’70s Show rather than portraying the KKK’s Grand Wizard. Cameos and supporting roles by Alec Baldwin, Michael Buscemi, and a riveting monologue by Harry Belafonte as a fictional civil rights leader help to cement the stellar cast.

BlacKkKlansman offers a welcome reboot of Lee’s aesthetic, which, according to Alyssa Rosenberg, verged on the “patently bonkers” in Chi-raq (2015). It taps into a range of genres and storytelling modes, suggesting the influence of Peele, including moments that channel Ava DuVernay’s historical voice from the Selma and the Netflix documentary 13th. This film, too, makes a deliberate point to tell the urgent history of the criminalization of black men during and after Reconstruction, as well as cinema’s role in the process via a chilling scene where we actually get to watch the Klan watch Birth of a Nation. The “bonkers” is certainly present here but tempered by gravitas as it was in Do the Right Thing, Lee’s most acclaimed film about a race riot in Brooklyn. Both DTRT and BlacKkKlansman offer powerful calls to reflect and take action, through pivotal, inevitable, irrevocable scenes of hate and injustice.

Lee has long expressed consternation at the criticism that DTRT was a potentially dangerous film, that its portrayal of racial violence would incite racial violence. It’s a great historical irony, then, as well as a vindication for Lee that BlacKkKlansman — a film where some violence to the black body is present, but where no black character or ally actually dies — ends with real footage of the Charlottesville white supremacist violence, where an anti-racist protester was killed and many more were injured.

In the film’s coda, the KKK attempts a final symbolic revenge. Patrice and Ron — both triumphant, powerful characters in Lee’s cinematic world — are rendered one last time as two fearful, vulnerable people, who defensively cling to handguns as Lee floats them down a hallway using his signature double-dolly shot. An open window reveals why: The Colorado night has been disfigured by a burning cross, and hooded men carrying torches. Then, there is an abrupt cut to 2017, and footage from the real Charlottesville rally, including a glimpse of Trump’s shameful equivocations, as well as harrowing scenes of panic surrounding the infamous car attack that left Heather Heyer dead. This is the most graphically violent footage in the entire film. Whether or not it’s a legitimate question to ask if DTRT was ever responsible for inciting violence, it’s abundantly clear that the black people holding guns, in 1972, at the end of BlacKkKlansman do so entirely in self-defense against a real and apparently rising threat to those who would challenge white supremacy. Surely Lee means to evoke the epigraph with which he ended DTRT, from Malcolm X: “I don’t even call it violence when it’s self-defense; I call it intelligence.”