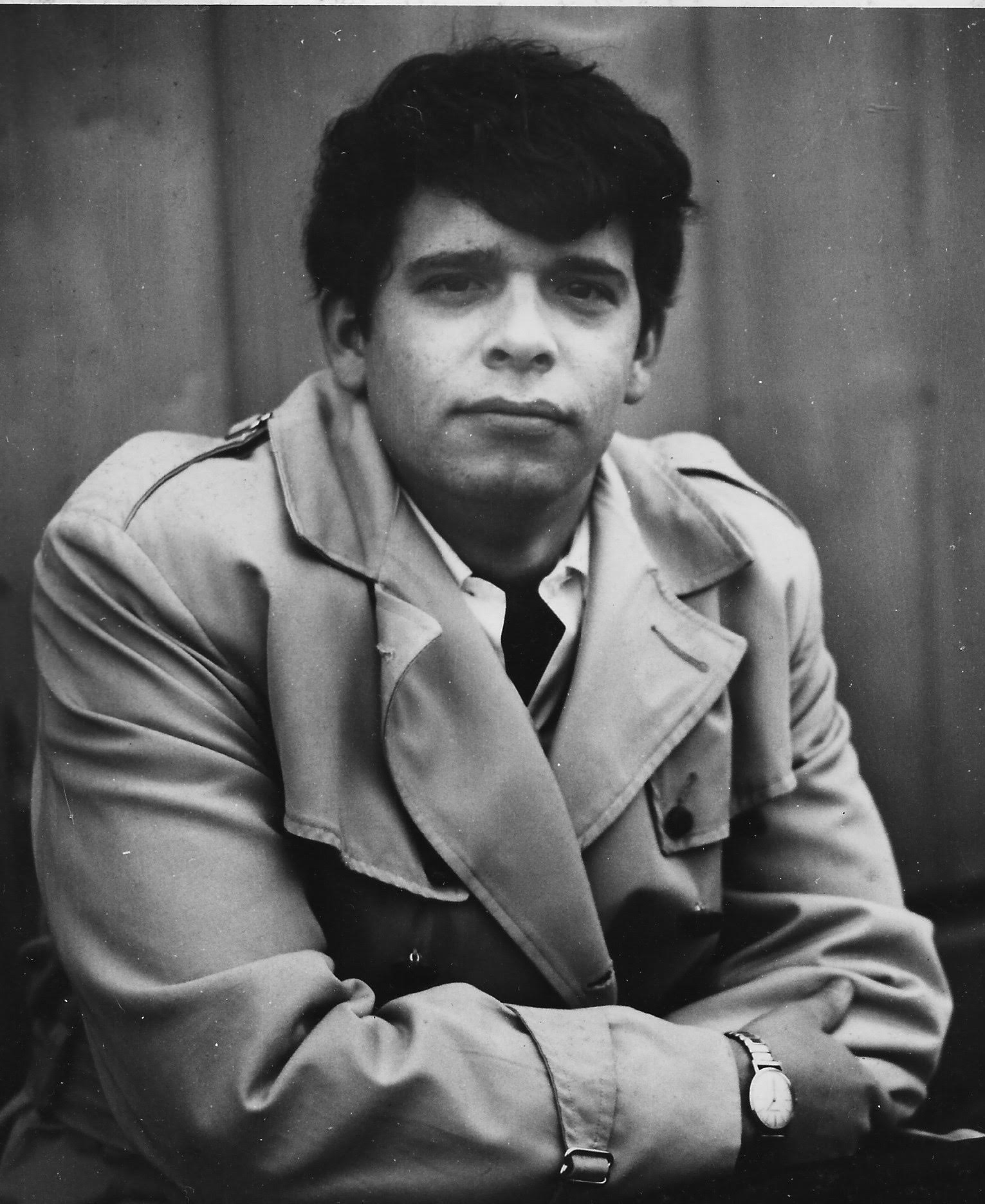

Daniel Lentz, a noted composer with a global audience and reputation, died in Santa Barbara on July 25 of heart failure.

Daniel was labeled a minimalist (or post-minimalist) composer, but — as the Independent’s Joe Woodard has noted — he rejected comparisons and defied categorization. He was known for his innovations in electronic music, but he also wrote pieces for wine glasses (with performers drinking wine to vary the pitch). His pieces incorporated Catholic liturgy, such as his several masses; Seneca ritual dances; modern physics, in works that evoked the Big Bang and string theory; and food, in pieces inspired by French meals.

He kept listeners off-balance; the Los Angeles Reader described his style as “tossing knuckleballs into extant musical traditions, but doing so with disarming grace.” Paul McCartney said that On the Leopard Altar was “a crazy record … should’ve been a hit.”

Above all, Daniel was a romantic, always in pursuit of beauty. The Village Voice in 2001 declared, “Lentz writes pretty, pretty music, but of so many kinds that you find you never realize how many shades of pretty there are.”

Daniel was born and raised near Latrobe, Pennsylvania, and developed an early love of music, playing trumpet in a jazz band in high school. He attended St. Vincent College in Latrobe, majoring in music, and discovered the music of Stockhausen, Cage, Boulez, and other modern composers. He obtained an MFA in music theory/composition at Ohio University in 1965 and pursued further graduate study at Brandeis, where he began working in electronic music.

In 1963, he married his high school sweetheart, Marlene Wasco, and two years later, they had a daughter, Medeighnia. After a fellowship at Tanglewood and a Fulbright fellowship in Sweden, in 1968, he moved with his family to Santa Barbara for a faculty position in UCSB’s College of Creative Studies, where his courses included a hugely popular history of jazz and where he tested the tolerance of university administrators for avant-garde art. In 1972, he was the first American to be awarded first prize in the Stichting Gaudeamus, an international composer’s competition.

He then left UCSB to pursue an independent life of composition. He founded a series of ensembles — the California Time Machine, San Andreas Fault, and Daniel Lentz Group — that toured the U.S., Canada, and Europe. The Daniel Lentz Group, formed after he moved to Los Angeles in 1982, pioneered the real-time use of multi-track recording in live performances and performed with the L.A. Philharmonic, the Philip Glass Ensemble, and other symphonies. In 1991, he accepted a position at Arizona State University, where he taught for 10 years.

Daniel gathered no moss, at various times living in L.A., West Berlin, Paris, San Francisco, and Albuquerque. But he lived for the longest in Santa Barbara, more than a third of his life, and he considered it home. He returned here for good in 2007 and continued to compose and record new music. He also began combining music with visual art in his Illuminated Manuscripts, three-dimensional acrylic renderings of the score of a recorded musical piece that accompanied the artwork. He had recently started work, at age 84, on a new piece for a concert in Japan.

He recognized, after the fact, that where he lived had influenced his music, starting with bluegrass and polka in the hill country of western Pennsylvania and Gregorian chant from the monks at his college. Santa Barbara’s well-lit days and slowish pace resulted in music reflecting an environment of sunshine and ease. In L.A., his music became more energetic, dissonant, and international, reflected in his piece An American in L.A. for the L.A. Philharmonic. He was both criticized and praised for his California sound by the music media, from L.A. and New York to Europe and Asia. In 1987, the Los Angeles Reader declared, “Which composer best represents Los Angeles? Could it be, oh, I don’t know … Daniel Lentz?” When he moved to the Arizona desert his music grew darker, evident in his Apologetica to indigenous peoples.

His extensive discography included “Missa Umbrarum,” a marriage of contemporary and gothic; “Point Conception,” in which nine overdubbed pianos (recorded by area pianist Arlene Dunlap) go in and out of synch; “wolfMASS,” a liturgical mass that intertwined 14th-century music by Guillaume de Machaut with “Yankee Doodle” and “When Johnny Comes Marching Home”; and “crack in the bell,” a musing on a poem by e.e. cummings.

Daniel loved good food and wine, cigars, dogs, wordplay, and interesting, smart, creative people. His sense of humor was so subtle that you sometimes didn’t know if he was joking. He was competitive, whether at arm wrestling or Ping-Pong. He was an outstanding cook, and in Santa Barbara, he lived European-style, walking to the market each day for provisions, even if the market was Trader Joe’s, a mile away. Daniel was endlessly creative and he refused to compromise his artistic vision for commercial success.

He is survived by his daughter, Medeighnia (Peter) Westwick; grandsons Dane and Caden Westwick; brother George (Barbara) Lentz of Ligonier, PA; and sister Julie (Bob) Filippone of Pittsburgh, PA.