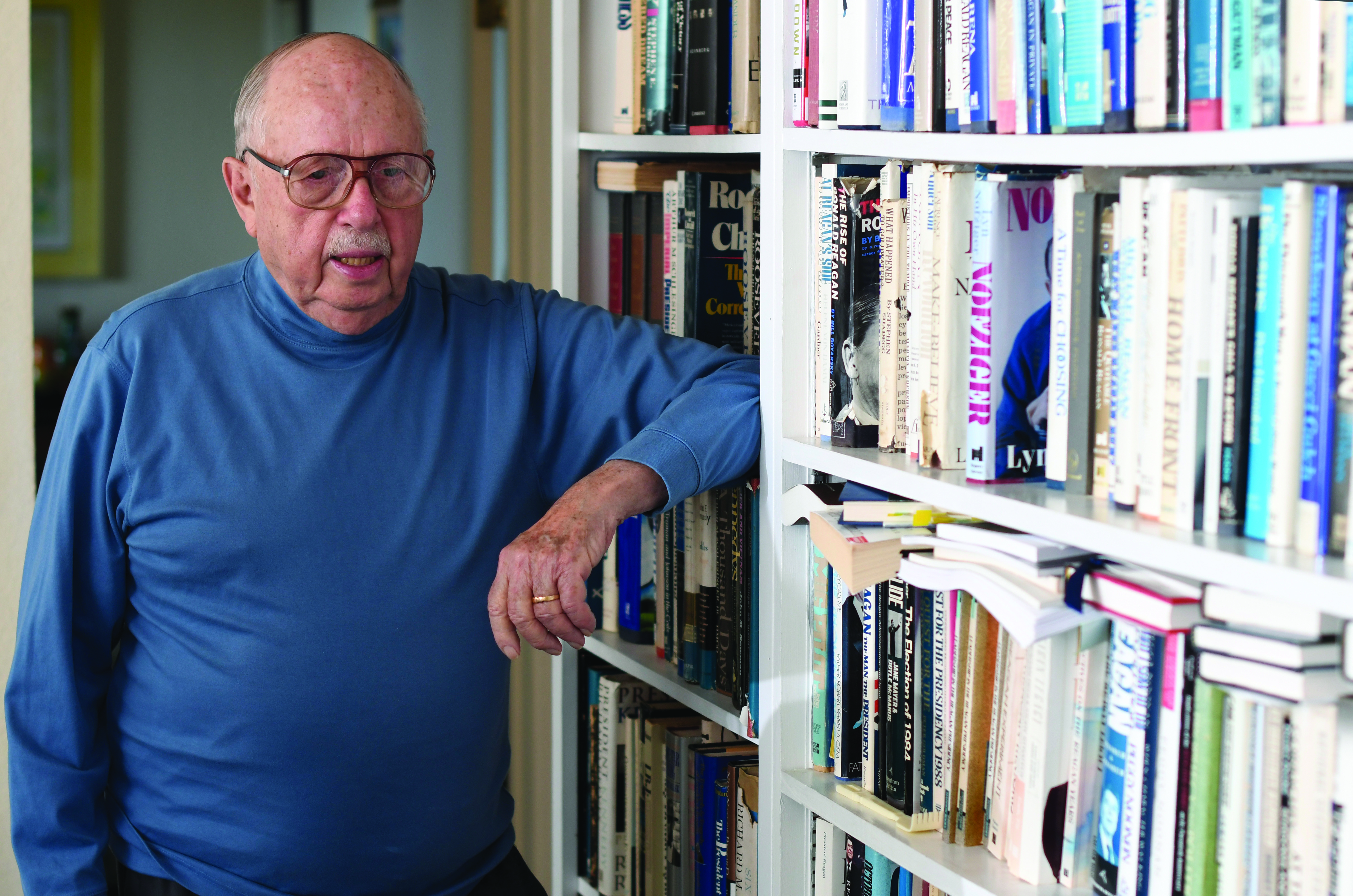

Lou Cannon, the eminent biographer of Ronald Reagan, and a caring, civic-minded, and consequential citizen of Santa Barbara, died on December 19 at Serenity House.

He was 92.

A legendary journalist, Cannon earned a national reputation for uncommonly rigorous, thoughtful, and fair-minded reporting. In addition to his eight books, including five on Reagan, he was a prolific daily newspaperman and wrote the first draft of history in countless articles about politics and public policy.

In Santa Barbara, where he lived for more than a quarter-century after retiring from the daily news grind, he was a colleague, confidant, and mentor to many working in local media and politics. He also was a kind and generous friend to those he came to know as he relished the delights of his adopted hometown, from the Music Academy to the Harbor Fish Market and tai chi classes in the Alice Keck Park Memorial Garden.

“He was just ‘Lou,’” recalled retired tech executive Gordon Morrell, who met him in a group that assembles weekly at the garden to practice the 108 choreographed moves of tai chi. “A few of us would gather around him after class to discuss politics, but most people didn’t know this was a man of some import.”

Said Carl Cannon, Lou’s oldest son, a prominent Washington journalist: “When he settled in Santa Barbara, that was his home. He loved Summerland — that was his town.”

Authoritative Biographer

Lou Cannon grew up in Nevada and began working low-wage jobs at small newspapers, after service in the U.S. Army, in the 1950s.

He landed on the copy desk at the San Jose Mercury News, then worked his way up at the paper to become Sacramento bureau chief in 1965, just in time to cover the unlikely rise of Ronald Reagan. Chronicling Reagan’s first term as California’s governor, Cannon began to master the complexities of government while cultivating deep news sources he mined for decades.

Hired by The Washington Post in 1972, Cannon served as chief White House correspondent during the two terms when President Reagan became the nation’s most transformational leader since FDR.

“His greatest service,” Cannon wrote later, “was in restoring the respect of Americans for themselves and their own government after the traumas of Vietnam and Watergate, the frustration of the Iran hostage crisis and a succession of seemingly failed presidencies.”

His five books about Reagan include the best-selling President Reagan: The Role of a Lifetime in 1991, and Governor Reagan: His Rise to Power in 2003.

Since Cannon’s death, major news organizations have praised his huge talents for biography, history, and political reporting.

“In a crowded publishing niche,” said The New York Times, “Mr. Cannon was widely regarded as a foremost authority on the president. He had extraordinary access, traveled with Reagan, interviewed him some 100 times and admired and respected him.

“Yet his … books on the president were never adoring. Indeed, reviewers generally found them to be models of objective reporting whose assessments of Reagan tended toward the negative,” the Times obituary said.

Ken Khachigian, a veteran California and Reagan strategist — whose political career began in the 1960s as UCSB’s Associated Students president — recalled, “If I had something to say, I put it out there and knew that Lou would tell it straight without putting a twist on it, or shading it with his own point of view.

“It was clearly the same when it came to his books on Reagan,” Khachigian said in an interview. “He belonged to an era of [reporters] who didn’t … tilt the notebook going in, but just wanted to tell a story, find a great lede, and bust the balls of the competition.”

Cannon penned perhaps the drollest line ever written about Reagan, who took great pleasure in vacations and naps: “He may have been the one president in the history of the republic who saw his election as a chance to get some rest.”

Carl Cannon said that his father, who left the Post in 1998, chose to retire here after savoring Santa Barbara while covering Reagan’s trips to his Rancho del Cielo.

“He was with Reagan a lot at the ranch,” Carl said. “After Reagan’s presidency, he came back to California, and so did my dad.”

Mr. Santa Barbara

Lou is survived by his wife, Mary; by three children from a previous marriage: Carl, Judy, and Jack; seven grandchildren; and seven great-grandchildren. Another son, David, preceded him in death.

In Santa Barbara, the Cannons had a wide circle of friends, many of whom rallied as the couple faced health challenges in recent years.

In interviews, they offered personal glimpses of a friendly, engaging, and civic-minded man, genuinely interested in other people, who enjoyed good conversation and a good meal, favoring plain and filling fare at local establishments such as Clementine’s Steak House, the Nugget Bar and Grill, and the Summerland Beach Café.

“As legendary as Lou Cannon was, what stands out most to me was how consistently kind and gracious he was,” Supervisor Laura Capps told Josh Molina for a News-Press.com obit. “He always asked about others. He paid attention.”

Ann Louise Bardach, author of multiple books about Fidel Castro, bonded with Lou over the travails of biography and welcomed him as a congenial dinner party guest. She laughed at the memory of Lou hustling over whenever her plum tree bore fruit.

“He came to every party,” she said. “And he’d come over every year and pick several hundred plums. We made plum jam — Lou loved jams and marmalade, but he’d say, ‘They’re not sweet enough.’”

Her husband, the actor Robert Lesser, connected with Lou over classical music.

“Lou loved the Music Academy — especially the master classes and teaching seminars,” Lesser remembered.

Realtor Marco Farrell met Lou through his father, who sold the Cannons their house. The families became close, and Marco became a reliable Mr. Fix-It. Among other informal duties, he would drop off shepherd’s pie or another homemade dinner from his mother. Last month, before learning that Lou had suffered a stroke, his third, she worried because he hadn’t called the day after delivery of her latest pea soup.

“He always called to say ‘thanks,’ and she became concerned when he didn’t,” Farrell remembered. “Lou was humble, soft-spoken, and always thinking of others.”

UCSB professor Laurie Harris recalled Lou, in trademark tattered ball cap or blue beret, stopping with her at Albertson’s, for his standing order of rye bread, or at the fish market, for Hope Ranch mussels, Scottish salmon, and tartar sauce, to cook at home.

“Lou went out of his way to get to know the people around him,” she said. “He engaged with people who worked at the bakery or the market, noticed them, knew their names.

“He thought of himself as a local,” Harris added, “and Summerland as his hometown.”

A Man Who Mattered

Lou followed local politics closely. Irate about the closed-door machinations behind the controversial county cannabis law, he reached out to Laura Capps in 2020, when she challenged the incumbent supervisor who pushed it through.

“He was horrified at how that ordinance got rammed through,” Bardach recalled. “He thought long and hard about it, and then said, ‘I am leaving political neutrality behind on this one.’”

Capps recalled first meeting Cannon in 1994, when he interviewed her father, the late Walter Capps, who was running for Congress for the first time — “My dad was a little starstruck” — and later knew him slightly through her mother, Lois, who succeeded her husband in the House of Representatives.

But she was amazed when he offered to help her campaign for supervisor.

“I was incredibly flattered that my little race would rise to the importance of someone who had covered the White House,” Capps said. “He was such a great figure — ethical, sage, soft-spoken — but never offered advice without being asked. Lou didn’t need to cram his expertise down your throat.”

Lou entered another local fray: the 2006 struggle at the old Santa Barbara News-Press newspaper, where billionaire owner Wendy McCaw waged journalistic, economic, and legal warfare against her own staff (me included) and those who supported them.

“Lou had the courage to stand up to a billionaire bully when other members of the Santa Barbara establishment were running for cover,” recalled Melinda Burns, who led the staff union effort. “It was an unforgettable declaration of solidarity.”

In his send-off for Lou, Independent columnist Nick Welsh recounted Cannon’s pugnacious written exchanges with McCaw.

McCaw set things off with an ad hominem attack in her paper after he expressed strong public support for the workers — “Mr. Cannon exemplifies what is wrong with today’s journalistic elite,” she wrote.

When her paper wouldn’t print his response, he turned to the Independent and the Los Angeles Times, which published his commentary on the matter: “I am not beholden to any party, government, sect, faction, corporation, union,” he wrote in part, “nor to anyone, like yourself, who believes that your wealth entitles you to harass, smear, and intimidate honest people.”

Lou’s actions in that painful chapter of local history drew national media attention, elevating a small-town business tussle into a high-stakes industry showdown. With great moral clarity, he used his personal stature to explain the heart of the matter: the importance of ethical journalism produced in the public interest, not squandered on special interest agendas.

No one knew it at the time, but it would prove a prescient struggle — one that, sadly, metastasized nationally in decades since.

Lou Cannon didn’t have to put himself on the line in that long-ago fight — he had a nice, quiet life writing books in Summerland.

He lent his reputation, his integrity and his moral authority to it, however, because he knew it was the right thing to do — for journalism, for justice, and for Santa Barbara.

RIP, old friend.

Correction: The date of death has been corrected to December 19, 2025.

You must be logged in to post a comment.