In the closing days of World War II, as the world struggled to comprehend the magnitude of Nazi atrocities, a young American psychiatrist named Douglas Kelly was given an extraordinary assignment: to study the minds of the men who had orchestrated the Holocaust. Among his subjects was Hermann Göring, Hitler’s designated successor, the architect of the Luftwaffe, and one of the principal engineers of genocide.

The 2025 film Nuremberg brings this forgotten chapter of history back into focus, and with it, a question that resonates uncomfortably today: How do we understand monstrous acts committed by people who seem so utterly convinced of their own righteousness?

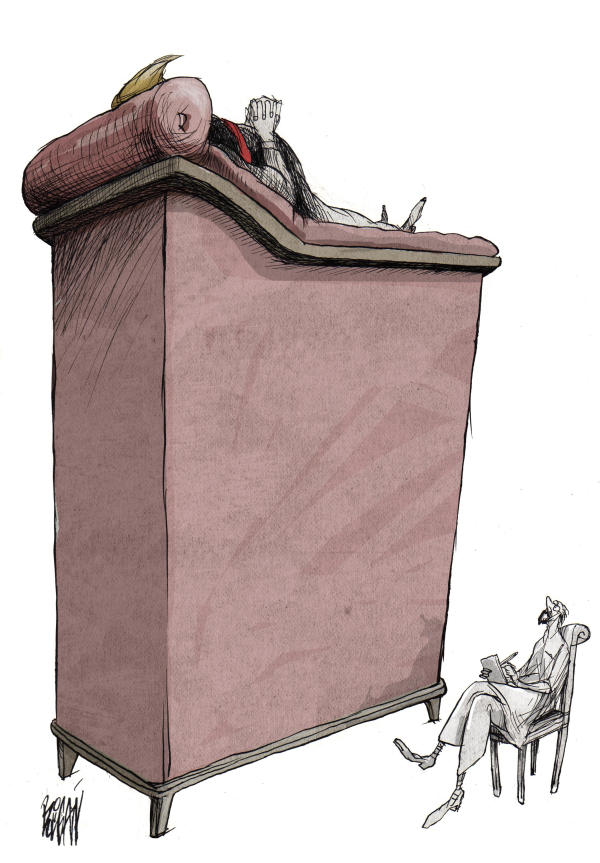

Kelly spent months with Göring in his cell, conducting psychiatric evaluations, administering Rorschach tests, and engaging in lengthy conversations. What he discovered challenged the prevailing narrative that the Nazis were somehow fundamentally different from other human beings — a special breed of German cruelty. Instead, Kelly identified something clinically recognizable: Göring exhibited classic symptoms of severe narcissistic personality disorder.

The diagnosis was revelatory. Göring’s grandiosity, his pathological lack of empathy, his charm deployed as manipulation, his inability to accept responsibility — these weren’t the marks of a uniquely German evil. They were symptoms of a personality disorder that transcends nationality and era. In contemporary diagnostic terms, Göring would likely have met criteria for multiple Cluster B personality disorders: primarily Narcissistic Personality Disorder and Antisocial Personality Disorder, with elements of Histrionic and Borderline features.

The Dangerous Logic of Ego-Syntonic Disorders

What makes these personality patterns particularly dangerous in positions of power is a quality clinicians call “ego-syntonic.” Unlike depression or anxiety, guilt or shame, which feel distressing to the person experiencing them, personality disorders feel normal — even superior — to those who have them. The narcissist doesn’t wake up thinking, “I have a problem.” They wake up thinking, “Everyone else has a problem.”

Göring never wavered in his self-justification. Even facing execution, he remained grandiose, unrepentant, convinced of his own brilliance. He blamed others — the Allies, circumstances, subordinates — but never himself. This is the hallmark of ego-syntonic pathology: an impermeable sense of rightness that no amount of evidence or suffering can penetrate.

When Kelly tried to confront Göring with the reality of the concentration camps, Göring deflected, minimized, rationalized. The Jews were a threat. Orders were orders. He was simply doing what was necessary. The absence of internal conflict — of conscience — was complete.

This absence is what allows narcissistic and antisocial personality patterns to cause such catastrophic harm. A person plagued by doubt, empathy, or moral ambivalence has internal brakes. But when personality pathology reaches the levers of power, those brakes don’t exist.

A Pattern That Never Ends

Today we see Stephen Miller ordering ICE agents to deport more than 3,000 immigrants daily, with no trace of self-doubt or empathy. We see President Trump calling Somali refugees “garbage.” Trump’s scapegoating and warmongering (e.g., Venezuela, Greenland) could be seen as a heartless manipulation to distract the public from the deep economic challenges that they are facing. Trump’s lies mimic Hitler’s infamous aphorism, “the bigger the lie, the more likely it will be believed,” which in both cases points to the antisocial and arrogant nature of their inner workings. The narcissistic leader thinks that people can be manipulated seemingly forever, but people know that a lie is a lie.

Why This Matters Now

The lesson of Kelly and Göring isn’t that every narcissist becomes a war criminal. Most people with personality disorders never harm anyone but themselves and those closest to them. The lesson is about what happens when these patterns go unchecked at the highest levels of power.

Democracies were designed on the assumption that leaders would have at least minimal internal constraints — some capacity for shame, some recognition of fallibility, some responsiveness to moral reasoning. But personality disorders create individuals for whom these constraints don’t exist. They experience their own grandiosity as simple truth. They experience their lack of empathy not as a deficit but as a strength. They experience moral criticism not as information to consider but as an attack to be crushed.

This is why such individuals can order family separations, spread conspiracy theories that lead to violence, undermine democratic institutions, or engage in corruption — all while sleeping soundly at night. The ego-syntonic quality of their pathology means they feel entirely justified.

Kelly believed that understanding the psychology of men like Göring could help prevent future atrocities. He thought that if we could recognize these patterns early, we might prevent them from causing catastrophic harm. Tragically, Kelly himself later died by suicide, perhaps overwhelmed by what he had learned about human nature.

Kelly’s insight remains essential: Evil doesn’t require monsters. It only requires personality pathology in positions of unchecked power.

As we watch Nuremberg and witness Kelly’s careful documentation of Göring’s psychology, we might ask ourselves: Are we watching history, or are we watching a warning? Will we recognize these patterns when they appear in our own time, in our own politics?