I’m tempted to think of Barry Spacks as the elephant in the Santa Barbara poetry room. As Chryss Yost has said, he was a creative force we couldn’t just talk around but had to acknowledge as central, not only to poetry but with excursions to the other arts. In doing so, we were like the blind men describing that other elephant in the old fable. One of us — it could be myself — touches and hears the trunk and exclaims: “A Poet!” Correct! This revelation has come to every Santa Barbaran who cares about poetry, even before Barry became our first poet laureate.

Slogging through the May 1966 issue of Poetry magazine, my spirits were suddenly lifted by two bright and sparkling pieces by someone at MIT, whose name I had just read on a letter of recommendation to UCSB: Barry Spacks. One of those spirited poems parodied what he had written seriously, and it was mischievous (this MIT Spacks was the Poet), being titled “Recommendations”:

This is a good fellow

who knows what he may do?

He is most excited, he is walking

the walls of himself

on tiptoe. Give him

a prize.

And this one is steady:

it is clear that he is breathing;

he will never kill any number

of old ladies, nor harrow

hell. Give him

a prize.

(William Faulkner in an interview had said, “Keats’s ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ is worth any number of little old ladies.”)

I wrote Barry an AUTHENTIC UNSOLICITED FAN LETTER, and after a great deal of correspondence, I booked him for the fourth issue of my magazine, The Little Square Review. In my “note” there, I wrote:

The poems are imbued with the freshness that comes only to a man who remembers his body, but they could be written only by one who takes an equal care of his mind.

Barry had replied to my fan letter: “Since poetry has so adjusted to a medium of solitude, it comes as an energizing shock to discover someone attending.” Also he lamented: “The great danger for all of us nowadays, don’t you think, is to yield to a sense of personal irrelevance?” Yes, that was so, back then, and if it now seems that art has grown big enough to supply an elephant in our Santa Barbara, Barry’s presence and example have made an enormous difference, which his diffidence in 1966 would not have foreseen.

The blind person at the hind end of the elephant feels the tail: something like a paintbrush? “An Artist!” Yes. In recent years Barry showed his paintings, distinctively sketchy and often literary. (A poster he made as Poet Laureate for a city tree-planting occasion was a Concrete poem: “St. = Street without tree.”) As an artist he admitted two things: One, he had been painting for 20 years before he showed any work, and two, he was color-blind. To counter that handicap, he shared a studio with Neal Crosbie, whom he would consult as to whether a green, which looked gray to him, would go well with this section of chartreuse, which also looked gray.

An elephant has four legs like tree trunks. One, a blind person might think, would stand for his grounding in childhood, the son of a grocer who went to the Produce Market in Philadelphia at 4 a.m. every day. One of Barry’s boyhood chores was to stack the fruits and vegetables in bins, which may have led to not only a will for discipline but a love of food, expressed in such poems as “The Artichoke” or “The Onion,” and in allying himself with Kimberley Snow, the chef with a PhD in English in Lexington, Kentucky, and author of In Buddha’s Kitchen. The point about this “leg,” though, was his growing up in a Jewish district of Philadelphia and his anxiety for the “Assimilation” of Jews into American society, about which he published a poem under that title in the August 1979 Poetry, regretting its slow pace:

So maybe, say in ten thousand years,

Even the grim ones will start to join us?

(We who take jokes as a serious business) —

A second leg would be Barry’s fiction, best represented by two exemplary novels, The Sophomore and Orphans. The Sophomore, published in 1968, was unfortunately eclipsed by a similar but inferior coming-of-age novel, The Graduate, and though Barry was paid for writing a screenplay of his, the movie of the more famous one pushed it aside, like bad money driving out good, and it was never filmed. It was, however, reissued last year by Faber and Faber in London.

The second novel, Orphans (1972), is a very fine and moving story from Barry’s experience in the Korean War, a conflict about which very little fiction has been written. TV gave us M*A*S*H, of course, but only its famously stunning final episode (no laugh track) can be compared to the powerful plot and the poignant ending of Orphans. (Faber and Faber or the New York Review of Books Press: Reissue it!)

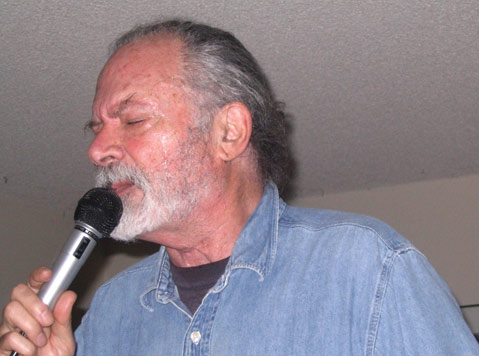

For a third leg, another blind man could propose Barry’s activities in other arts in Santa Barbara: “An Actor!” Yes, in at least four plays, including a musical by Victoria White where he played Gertrude Stein’s brother, Leon (Kimberley’s novel It Changes called him “Leo Stein”), and at UCSB in Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. And why not credit here his teaching, both in and out of school? His professional career divides in two, after undergraduate work at the University of Pennsylvania and a Fulbright year at Cambridge University. He spent 20 years in the hotbed of writers and academics in colleges and universities around Boston, teaching poetry and literature at MIT while his first wife, Patricia Meyer Spacks, taught literature at Wellesley. The second half was measured out in the cooler ambiance of Santa Barbara, first in the English Department at UCSB, and later in the College of Creative Studies, until December 2013, when he began to feel exhausted by his final illness. In 1989, he won a UCSB Distinguished Teaching Award and was always very highly rated in student evaluations for his enthusiasm and knowledge, as Teddy Macker’s online Independent article attests.

The elephant’s fourth leg is Tibetan Buddhism, which I believe Kimberley Snow had been practicing for some time before Barry. For six years, they were based in a Tibetan Buddhist community in Northern California. In what may be his most widely known poem of recent years, “Within Another Life,” he speculates on several transmigrations a soul might make after death — becoming a boulder, a pane of glass, a door — and expresses a final hope for his own:

And if a knotted, twisted rope

from long self-clenching and complexity,

oh love, unbind, unbraid me then,

until I flow again like windswept hair.

The elephant’s tusks are for fighting, seemingly essential for professors of literary criticism. But although well aware of the civil and uncivil wars in English departments, Barry did not take up the style of confrontation but its opposite: conciliation. In essence, his was a creative, not a destructive, talent, whether in his own work or helping others with theirs. To attest to his editorial skills, I cite my personal experience. As reader for the MIT Press, Barry had first turned down, as needing editing, the original manuscript of a book my wife and I had written about our deceased “special child.” Then, unpaid, and communicating cross-country by letter, he generously and cheerfully worked together with us, painstakingly helping us cut and reword, making possible its eventual acceptance. These critical skills were always available to anyone whose poems he was asked to assess, in numberless formal and informal poetry workshops and private sessions in person or online. Barry must rank as one of the most collaborative of modern American writers, which requires a diminishing of the ego in all parties concerned.

One more facet of elephant and human life might be alluded to in light of Barry’s continued emphasis on its enjoyments, in his poems as well as the novels. It’s succinctly stated in his posthumously published blurb to Diana Raab’s current book, Lust, which, he says, “celebrates the sacred everlasting Eros.”

Others will have more to say about Barry’s years in Santa Barbara. While he merged with the local arts community, I was engulfed by duties at the university. After retiring, I was more in touch, joining the monthly poetry workshop (now a hotbed of Santa Barbara poet laureates), which he had started. His devastating last group email came on January 6: “I have rather bad news from my doctors looking into my present state of exhaustion and won’t be able to be with you on the 19th. I’m afraid my strength doesn’t allow for visits, but I know you’ll all be thinking of me.” In other words, “over and out,” as radio operators said in World War II. Or, better, the valediction with which Barry closed his emails in recent years:

“On! On!”