When Joseph Charles Nuñez was born, his sister Lori tried to say “Joseph Baby,” and it came out “Joby.” He’s been Joby ever since. It is appropriate that his name resulted from a bridging of words because he will always be known for building bridges, in the form of human relationships.

In a region where there are spirited athletic rivalries among three high schools — Santa Barbara, San Marcos, and Dos Pueblos — Joby was a coach at all three. When his funeral mass and celebration of life were held on February 9, hundreds of friends from Goleta to Carpinteria — and former UCSB football teammates from afar — spilled out the doors of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel Church and filled the grounds of the Carriage Museum.

“He’s one of a kind,” said Mel Carrozza, who came out from New York. “I’ve never seen so many people. Everybody has a conduit to Joby.”

As an athlete, Joby was a three-sport (football, basketball, baseball) standout at Santa Barbara High. “He’s probably the most underrated all-around athlete we’ve had,” said Mike Moropoulos, a longtime Dons football coach. “He was the epitome of a single-wing tailback. He could run, throw, and lead. What stands out most is his positive attitude. You never had to say, ‘Hustle!’ or ‘Come on!’ There was something right in his upbringing.”

Joby’s parents were both teachers at Santa Barbara Junior High. His father died when he was 5. Moropoulos remembers Joby’s mother, Beatrice, as somebody you did not mess with. “She was tough on him,” he said. “Joby was in love with her.”

Nuñez got a taste of big-time football at Oregon State and was on the roster of the famed “Giant Killer” Beavers who upset No. 1–ranked USC, 3-0, in 1967. But his heart was in Santa Barbara, and he finished out his career in 1969-71 at UCSB.

Carrozza and Brock Arner were Gaucho linemen who became lifelong friends. “Joby was about 59, 180 pounds, and could bench press 280-290,” Arner said. “He was an astonishing blocker as a wide receiver. He showed no fear. I would stand up a 280-pound defensive tackle, and Joby would take him out, just crush him.”

Jimmy Curtice, who had been a San Marcos High quarterback, was at the helm of the Gaucho offense. He recalled a 1969 game at Cal Poly: “We’re ahead 9-7 with two and a half minutes left in the game. It’s third and two on our own 28. They’d been beating us up. We had to get a first down or they’re going to come back and kick a field goal. We gave it to the only guy who they couldn’t touch: Joby Nuñez on a reverse. He went for nine yards, first down. We milked the clock and won the game.”

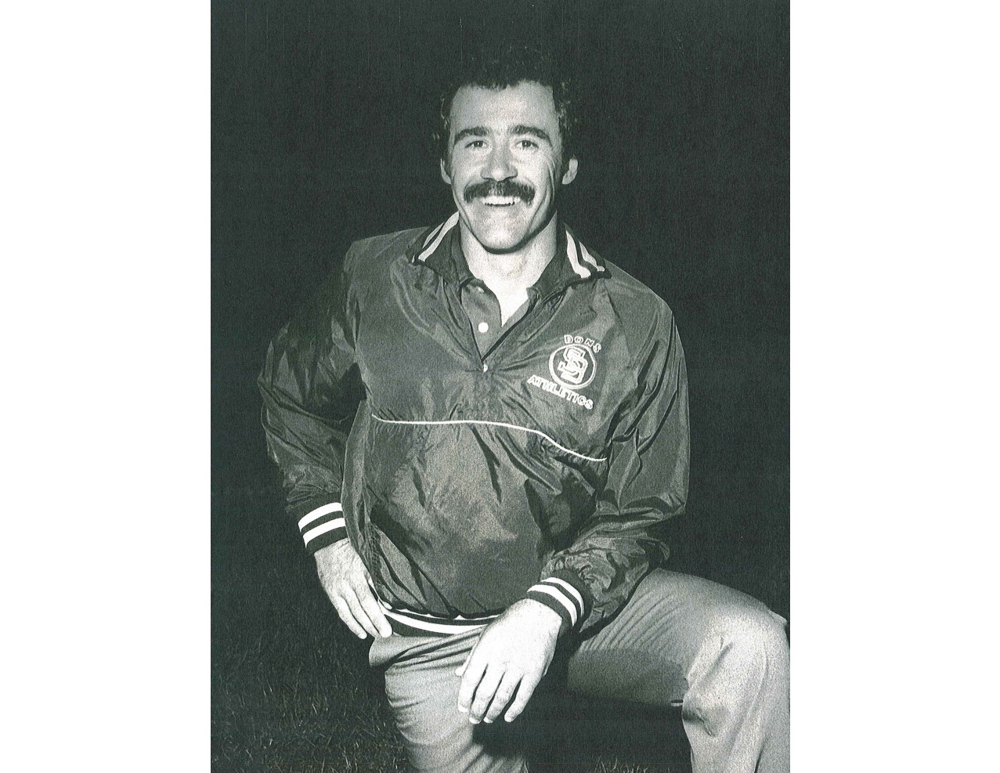

Teaching credential in hand, Nuñez got his first job at Dos Pueblos. “One of the reasons we hired him was that we knew he was a very coachable as an athlete,” said Dick Mires, the Chargers football coach. “He understood the kids.” That didn’t mean they always understood him. “He was a taskmaster, hard-core, a badger,” said Bruce Hopper, one of the defensive backs assigned to the young coach. “I butted heads with him a lot.”

Mires presided over a coaching staff that included the professorial Scott O’Leary, Tom Everest, Connie Barger, and Jeff Hesselmeyer. Only Mires and Everest survive. They had the Chargers playing at the UCSB stadium, taking on powers like Mater Dei and St. Paul.

During that time, Nuñez made an extravagant purchase: a red 1976 Porsche 911-S that he drove until his feet were weakened by neuropathy. “It was brand-new when I went to L.A. with him,” Mires recalled. “Joby was driving, and I was reading the owner’s manual to him.”

Nuñez also coached baseball and started the Dos Pueblos soccer program. Abe Jahadhmy, who went on to become a soccer coach himself at San Marcos and is the school’s athletic director, played for him. “Santa Barbara had great soccer players, but Goleta had nothing,” Jahadhmy said. “I learned about preparation from Joby. Soccer coaches didn’t scout other teams, but he did. He started soccer at the Goleta Boys Club. Eight years later, DP won the CIF championship.”

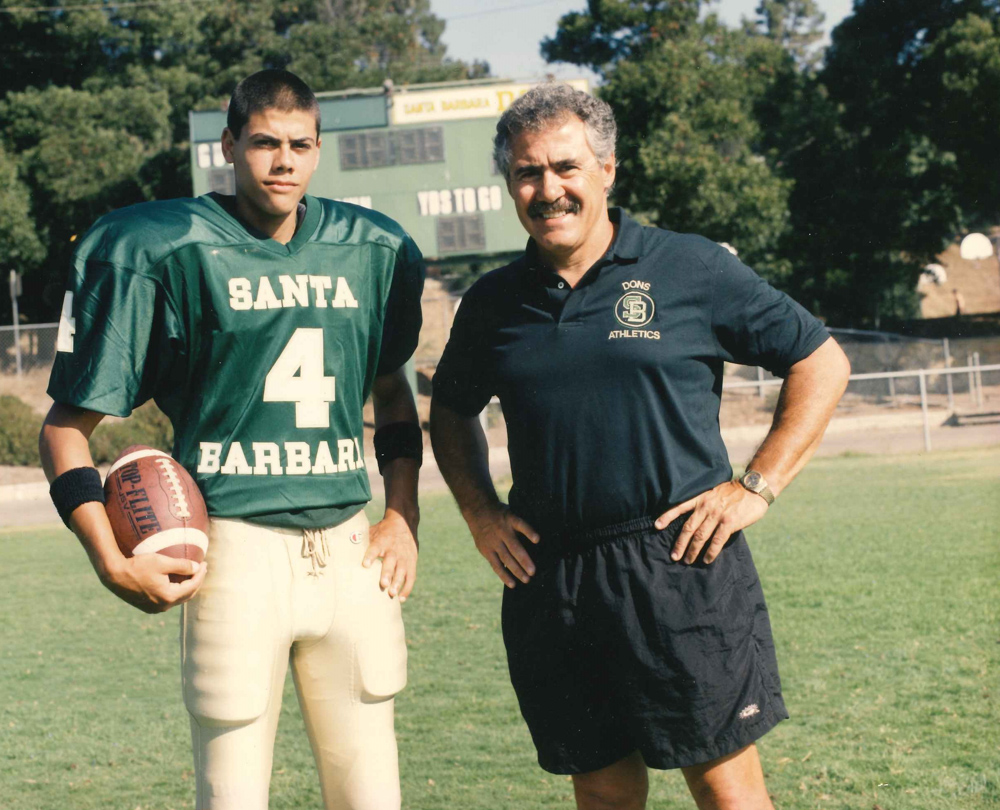

But Nuñez was laid off prior to that 1983 title because of widespread cutbacks in the school district. He commuted to a job at Nordhoff High in Ojai. “I talked to [principal] Bill Jackson and said, ‘You’ve got to make room for Joby,’” Moropoulos said. For the next 10 years, Nuñez taught and coached at his alma mater. He took the Dons soccer team to the CIF finals in 1989 and was defensive coordinator for Lito Garcia’s football team that won the CIF title that fall.

His last years in education were as an administrator at both San Marcos and Dos Pueblos, and he continued to be a mentor to students. When his friend Hesselmeyer took over as football coach at San Marcos in 2009, Nuñez came out of retirement to lend a hand.

He also got involved in the Ye Ole Gang, Santa Barbara High’s Hall of Fame organization, and other foundations. “He was always doing something for other people,” Moropoulos said.

Over the years, Joby acquired a huge roster of friends. He could not go out in public without running into a former player or student. “One of my most vivid memories was of him patting me on my back as a junior,” said Eric Bittle, an offensive line coach at SBHS. “It meant the world to me and is part of why I coach now, too. I loved seeing him later in my life as an adult. He’d ask about my wife, my kids. He saw more in you than a player on the field.”

For some, it took time to realize what Nuñez meant to them. “In the last 10 years, he was such a great guy,” Hopper said. “When we were kids, we had no idea.”

In a poignant eulogy at the church, Joby’s son, Danny, told a story about the Christmas Eve when he was 9. Spotting a man drunkenly staggering on the sidewalk, his father stopped the car. Not surprisingly, the man recognized him: “Joby, is that you?” Nuñez offered to give him a ride, pulled out $40, but the man refused to take it. “Just because someone has a problem does not mean that he is a bad person,” Danny remembered his father telling him.

Cancer invaded Joby’s body seven years ago, and he never burdened his friends with grave news. “We never talked about cancer,” Moropoulos said. “I had no idea he was sick; he was always so upbeat and smiley,” Bittle said. “He didn’t whine about it at all,” Jahadhmy said. “He was determined to enjoy life with his family.”

Joby and Pat Nuñez, a teacher herself, were married for 41 years. They raised three thriving children, Danny and his sisters, Janet Lemons and Ana Karina Arnold.

Karina, as she is known, made it clear that her father had a much wider embrace than his man’s world of coaching and games. “My dad was one of the most sensitive people I knew,” she said. “I always found comfort in knowing that no matter what it was, I could always go to my dad for sound advice, a good laugh, or a cry. My close girlfriends considered him like a second father because he loved and nurtured them as he did his own daughters.

“Words to describe my dad: approachable, loving, kind, nonjudgmental, fun, generous, sensitive, intuitive, funny, sarcastic, quick-witted, family- and friend-oriented, hard-working, sympathetic, and fair.”

That about covers it.