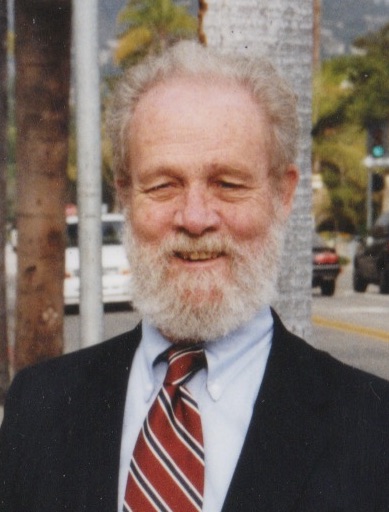

A brilliant writer, a wonderfully capable appellate lawyer, a kind and humble man — all these words describe my father, Jerry Franklin, a well-respected deputy district attorney in Santa Barbara for 35 years. He chose the law, or the law chose him — it’s hard to know which, but it was definitely in his blood, as my aunt Sheila Benson said:

Given our family’s dedicated political bent for generations, going well beyond our mother, a groundbreaking labor leader; or our cousin, a fixture in the New York State Assembly; Jerry’s first legal choices seemed almost pro forma.

He was a public defender (check), sharing offices with Legal Aid (check check), with no shortage of clients (check check check) in those days of unrest and protest that defined the late ’70s.

As we were catching up on the state of our lives by phone one afternoon, Jerry mentioned with the smallest shade of pleasure that his office had a great new addition: a donated couch. It gave his clients somewhere to sit.

“Ummm… Where had they been sitting, Jer?”

“On the floor.”

Sure. Absolutely. Silly of me to ask.

Jerry’s interest in the law went well beyond the influence of a cousin, who was a fixture in the New York State Assembly, or his mother, who was a groundbreaking labor leader.

Jerry’s mother, Mary McCall Jr., was a screenwriter and the first female president of the Screen Writers Guild. His father, Dwight Franklin, was an artist, costumer, and set designer. Jerry was born in Los Angeles, a twin, and he was preceded in death by his brother, Alan.

He received his JD from Boalt Hall in 1966. He then joined the Los Angeles Public Defender’s Office but left in 1968 to take up life in a VW van with his wife, Alison Reitz. They headed for Alaska but only made it as far as Argenta, British Columbia, where they lived for a year in a log cabin. They returned to Santa Barbara for my birth in 1970, just in time for Jerry to happily take up the defense of protesters in Isla Vista.

His friend Stan Roden was elected the county’s District Attorney in 1975, and when he was considering hiring Jerry, Roden recalled the reaction from the “hardliners” in the office and among law enforcement: He’s a radical. Never. No way.

“We hired Jerry,” Roden said. “He soon became an office favorite. Over the next 35 years, Jerry became the paragon of intellectual muscle for the DA’s Office. He researched and wrote many if not most of the important writs, appeals, motions, and trial briefs. He won praise from the bench and from other DAs as well.”

Ron Zonen, a formidable deputy district attorney who tried Michael Jackson and Jesse James Hollywood, among other high-profile cases during his career, said Jerry had a special place in his heart for con men. Jerry wanted them in jail and pursued them relentlessly.

He frequently helped other trial attorneys, Zonen said; in fact, it was common for a panicked lawyer in the midst of trial to ask for Jerry’s help to respond to a newly filed defense motion. Jerry would work late into the night and leave the finished brief on the lawyer’s desk: beautifully crafted, logical, and compelling. Assistant DA Pat McKinley once told a defense attorney who threatened to “paper him to death,” or file lots of motions, “You haven’t met Jerry. You have a peashooter; I have a Howitzer.”

Jerry lived humbly and gave away much of his earnings. One of his defendants, Zonen recalled, who took full responsibility for his crime and accepted his prison sentence gracefully, discovered that Jerry had put $50 per month in his prison account until he was paroled. “If someone was in need, Jerry pulled out his checkbook. If a staff member was dealing with prolonged illness, Jerry donated vacation time,” Zonen said.

For me, my father’s greatest gifts were his sense of play and delight in the world, a bottomless generosity, and his deep love of language. I absorbed his suspicion of authority and his parallel if not idiosyncratic love of the spirit of the law. He wanted to be a police officer but was kicked out of the police academy for being a smart-ass.

My dad had my back. He supported my every passionate inclination. The only caveats I remember were that I not get a tattoo and that I not sign up for “underwater basket-weaving” in college.

My parents divorced when I was 5, and my weekends with my dad were filled with fun. He taught me about “hiding in plain sight”: During one of our evening games of hide-and-seek at the Santa Barbara Mission, he completely stumped me by simply sitting on the edge the fountain with all the tourists while I looked in all the shadows for him. He would spend patient hours with me at the YMCA pool, teaching me to hold my breath and throwing dimes into the deep end for me to fetch.

I was only 14 when he taught me how to drive, determined that I learn to work a manual transmission and parallel park to perfection. Graduation was the 101 freeway at night, all the way to Los Angeles and back. He would pick up every hitchhiker we came across with a friendly, “Hey, brother!” A self-appointed first responder for any traffic accident, he would pull out the flares in his trunk and commence to direct traffic before the Highway Patrol arrived.

Jerry’s memory left him during his final years, and caring for him enabled me to attempt to repay his lifelong kindness. His love of wordplay and sense of humor remained to the end. The last conscious gesture he made was to give me the finger, which reassured me that although he was slipping away, both his humor and his awareness of my presence were intact.

I miss him every day.

You must be logged in to post a comment.