Dibblee Hoyt reveled in motorcycles, cameras, and vexing others, all of which manifested in 1988 on his epic 4,000-mile ride across Russia astride a BMW touring bike. The saga of that trip fused his loves of adventure and effrontery by his wild riding along Russian highways and posing with his bike on the steps of the Kremlin amid skeptical authorities and onion domes.

Dibblee first learned to ride as a young teenager in the early 1960s from his mother’s cousin Frederica Dibblee Poett at Rancho San Julian, where their family has raised cattle since 1817. Frederica let Dibblee, his brother Clay, and sister Antonia, fetch mail from the box on rural Highway One near Jalama — and generally cavort — on her green Vespa scooter. The Hoyt youth took their riding skills home to Mission Canyon and their friends from the Frost, Bottoms, Graham, de L’Arbre, and Forsell families, expanding their play areas from Rocky Nook Park and Mission Creek to the streets of Santa Barbara on small Hondas they rented near East Beach for $5/day.

Thomas Wilson Dibblee Hoyt, “Dibblee” to his friends and “Lee” to his family, began life in Cottage Hospital in 1950 as the son of Virginia Dibblee Hoyt and Robert Ingle Hoyt. His father was a noted architect who designed many homes and buildings, including the Santa Barbara Historical Museum adjacent to the presidio where Don José de la Guerra y Noriega served as comandante in the 1800s. Both of Dibblee’s maternal grandparents were great-grandchildren of Don José.

Dibblee attended Roosevelt Elementary and then Dunn School in Los Olivos. Dibblee and two friends once predicted the easiest way to obtain liquor and ice cream would be to steal them from a neighbor’s home. Their scheme went awry. From the back seat of a police car, Dibblee helpfully explained that his father was the architect who designed Juvenile Hall, to which the officer driving responded, “Then you’ll feel right at home there.” Dibblee’s father refused to get him released until the following day, explaining one night as an inmate was reasonable punishment.

Dibblee moved to Menlo Park to study journalism and graphics at Menlo College, though his friend John Chase reports Dibblee’s de facto college major was driving to Hollywood for weekend parties. After a couple years, Dibblee returned to Santa Barbara and with John rented a cottage just below City College. John recalls Dibblee driving his British racing green MGC six-cylinder roadster “like a mad dog” and taking his “contrariness to passionate levels” during those times.

Dibblee and John shared priorities — they kept several motorcycles in the kitchen. With easy access to the railroad across the street, they rode miles along the tracks unimpeded by traffic lights and stop signs. Once, while riding home beside the rails on a particularly loud Ossa Pioneer 250 dirt bike, Dibblee was chased by a deputy. Near Las Positas Road, Dibblee’s proficiency in riding on sharp gravel surpassed the officer’s, who fell and cut his knees while Dibblee escaped in the resultant cloud of profanity.

John began manufacturing motorcycle luggage in a bedroom on the Mesa and later a basement production facility in Montecito. His products’ success led to the Chase Harper company, where Dibblee wrote copy and handled shipping and receiving, though his stated job was company photographer.

Dibblee’s interest in photography had begun at age 6, when his father gave him a lightweight Kodak Signet camera. Dibblee learned to develop and print his images in a darkroom converted from a bomb shelter and later recounted that “this … began a long love affair with capturing images.”

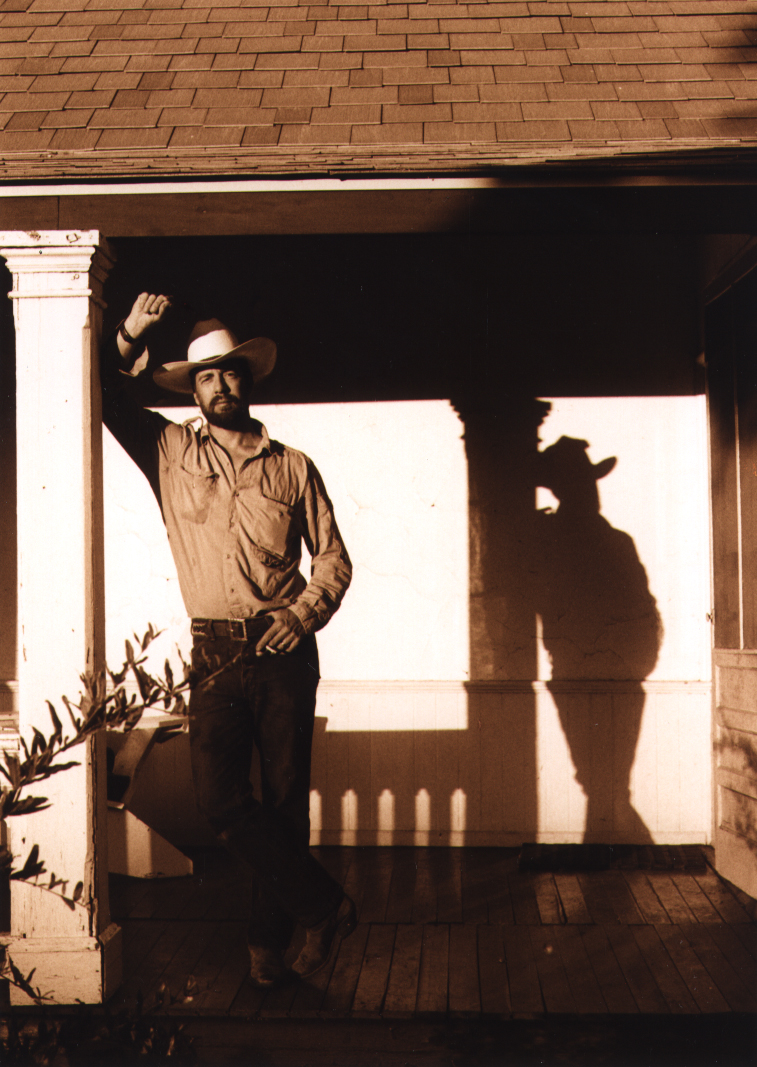

In his thirties, Dibblee moved to a run-down two-room 1910 board-and-batten house at the San Julian, where he shot its previous inhabitants, wood rats, from his bed with a .22 pistol. He wrote articles for Free 2 Wheel motorcycle magazine and turned his photography skills to the ranch hands and cowboys. He became well-known for capturing images up close and from unexpected angles during roundups and brandings.

Dibblee also captured the attention of Allan Hancock College in Santa Maria, which in 2002 asked him to teach photography. The Santa Ynez Valley Historical Museum and the Lompoc Museum exhibited his work; of the latter’s “Ranch Shots” exhibition, Bob Isaacson wrote Dibblee’s photographs “have a surprising authenticity, freshness, and originality.” By 2005, his success with students led him to receive Allan Hancock’s part-time faculty excellence in teaching award.

One student, Lynda Schiff, recalled, “Dibblee set up field trips that encouraged students to explore their own backyards … once, he was showing us some gorgeous shots he had taken at the Solstice Parade — he advised us to forget about the crowd, be bold, and step into action like we were supposed to be there.”

When Dibblee was in his late fifties, his friends and students noticed he was changing, both in personality and gait — he seemed forgetful and even more obstreperous. He was eventually diagnosed with a malicious form of multiple sclerosis for which there was no remedy.

The Santa Barbara Arts Commission soon put together a juried retrospective exhibition of photographs by Dibblee and his students to celebrate his art and the many students he mentored. In a review of that 2013 show, W. Dibblee Hoyt: Far Reaches, a reviewer complimented the “innovative and satisfying exhibition.”

Despite his advanced motor impairment, which left his BMW K75 and helmets gathering dust, Dibblee continued living on the San Julian, where he died at 71 last December 16.