A Memorial Day Salute

to a Father Who Loved the Sky

World War II Story of Young Soldier’s

Amazing Escape from Infamous POW Camp

By Geoff Yarema | May 29, 2023

Steve had been praying for this night for months — moonless pitch black would make him difficult to spot; bitter cold and snow would render heavily armed guards less attentive; howling winds would cover betraying sounds. No clouds ensured bright constellations.

Perfect for a navigator. He just loved the sky.

At 22 years of age, he had survived exactly 195 caged nights in German prisoner-of-war camps. He was determined next daylight would not find him again inside this hellhole.

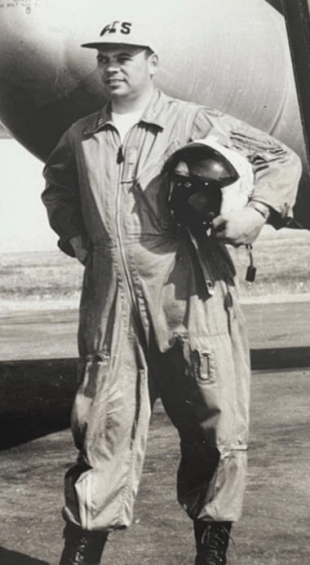

Steve had run away from an abusive immigrant father, lied about his age, and joined the Army Air Corps. He was determined to fly. And the quickly mobilizing war machine had obliged, sending his strong aptitude for math to Great Ashfield Airdrome, Suffolk, England, assigning him to the 385th Bomb Group and ranking him Second Lieutenant.

Soon his superiors were wedging his slight frame into the cockpit of a B-17 Flying Fortress. His role was bombardier. On sorties into well-defended enemy territory, he would synchronize tracking speed with ground speed, fix the crosshairs on the approaching target, open the bomb bays, and drop payload after payload.

He excelled at understanding the heavens.

After a solid run of successful missions, the odds caught up. On August 4, 1944, German anti-aircraft fire tore into his brand-new Douglas Aircraft–manufactured bomber nicknamed “Hair’s Breath,” sending it into a death spiral. He and the eight other young crew members acted mechanically, simply locking eyes and doing exactly as they had been taught. In sequence, they threw themselves out the open cargo door and counted the requisite seconds before pulling rip cords.

The Infantry cleaned and slept with their guns; the Air Corps packed and slept with their parachutes.

As he fell through air and space, time stopped. His view of the night sky was no longer from the overstory. Breathing in the overwhelming stench of diesel and death, he bore witness to his plane crashing into a million little pieces, one of many deafening explosions around him. He could not see the rest of his falling crew.

Preparing to hit the ground, he clearly recalled his coordinates — inside Nazi-occupied territory, near what is today the Danish-German border. The Third Reich had sent a welcoming party.

His new captors lost no time in moving him — southeast of Berlin to German-occupied Poland, ironically the country of his ancestry. Steve’s new home was Stalag Luft III, a truly foreboding compound. But its reputation for high security had been shaken just days before his arrival by the most ambitious breakout in WWII history, immortalized later in the movie The Great Escape. Through painfully, painstakingly, and clandestinely constructed tunnels, 76 men had crawled to freedom. All but three were soon recaptured.

Immediately upon entering this notorious camp, Steve was handed a shovel by Nazi guards. Over the next two weeks, as he worked to fill in the now-dynamited tunnels, he watched as the newly installed stalag commander demonstrated his new mandate. Steve and his fellow Allied officers were forced to bear bloody witness to the vicious, Hitler-ordered slaughter of 55 of the recaptured.

The resulting psychological scar, suffered long before PTSD entered the vernacular, would wound him for life, leaving him with extreme mood swings and blinding fits of rage, among other periodic reveals. As Faulkner admonished, the past is never dead. It’s not even past.

But the remarkable POW great escape had destroyed the camp’s reputation for invincibility. The remaining prisoners lost no time concocting new schemes, despite Poland’s worst winter in 30 years. Steve soon had his own idea and was determined to implement it — solo.

Unbeknownst to the Stalag III POWs, however, salvation was on the horizon. The Soviets were advancing hard, right toward the camp, and would soon liberate it. Steve unfortunately would not be among them.

A mere week before the Red Army’s arrival, the Nazis rousted the camp in the middle of the night and removed the resident American officers from the rest of the multinational detainees. Huddled outside in the brutal cold, Steve and his cohort breathed ominous. At daybreak, the reason became clear when they were ordered to take the first steps on what would become a brutal 400-mile forced march south, directly through the war-torn, chaos-strewn backbone of Germany.

After miraculously surviving this new trauma, what was his reward? Another internment — this time, Stalag VII-A, the Third Reich’s largest POW camp, then bursting at the seams with more than 70,000 prisoners. Among Steve’s new cabinmates were several of the legendary Tuskegee airmen.

At this point, he was done. Live free or die. The escape plan he had cooked up in Stalag III should transfer to Stalag VII-A, he reasoned. His new barracks had a trap door other POWs had hidden in the floor. The trick was getting from there to — and through — the camp’s heavily barbed-wire-fence perimeter.

Steve’s elegantly simple answer: a white sheet he would pull over his slight frame in prone, face-down position, corners fitted to each of his four extended appendages. With that in place, he planned to crawl — very, very slowly, from the bottom of the barracks over the constantly Klieg light–scanned winter terrain, hoping to be indiscernible from the surrounding snow to the watching guards.

His commanding officer had cleared his planned tactics — but only after looking deeply into Steve’s 22-year-old eyes and saying out loud what Steve already knew — that any detected movement would draw strafing machine gun fire.

On this carefully chosen, miserably bleak night he had been impatiently waiting for, the white sheet camouflaging his tortuous motion across the heavy snow had actually worked. Finally reaching the thickly protected perimeter fence, Steve produced wire cutters crudely fashioned from metal utensils and slowly cut through the bottom. His small size again proved an asset.

Soon he was outside. His escape had been undetected. For a moment, the euphoria was overwhelming. But he quickly returned to business. He was still well inside enemy lines. Many Germans — and German shepherds — lay ahead. But the Red Cross had discreetly provided intel if the opportunity were to arise. The resistance had a safe house less than seven klicks away. At least that’s what he had heard. Things could have changed.

Despite malnutrition, frostbite, and injuries from multiple beatings, Steve moved stealthily away from the compound. After only a couple of hours trudging through thick, snow-encased forest and flitting along the sides of deserted, bitterly windblown village roads, Steve quietly approached a nondescript, unmarked door. Taking a deep breath, he knocked three, then one, then two times. Just a few seconds later, an old man appeared and quickly swept him through.

Thankfully, the Red Cross information was still current. For the very first time that night, he allowed himself to breathe. His plan had worked. He was no longer a POW.

The man and his wife wrapped him in blankets and served him warm broth. Steve told of his journey and thanked them deeply for being there to guide him on his next challenging steps. But the couple quickly laid waste to the adrenaline coursing through his veins.

The good news was that the Germans were losing. Soon, Allied Forces would be occupying the area and the war would be over.

The bad news was that the escape routes Steve might take from there were safe for no one. The Allies were carpet-bombing the countryside all around them. With only one exception — the POW camp from which he had just escaped. The truth they proffered — the safest place for now was back in Stalag VII-A.

Steve struggled to process what they were urging. Reverse his escape? Seek to return to captivity, alive and undetected, to maximize his safety? Should he trust these strangers’ war intelligence? The cognitive dissonance was mind-blowing. But he did not hesitate. Steve knew that, with daylight fast approaching, he had not a moment to waste. He stood bolt upright, bid auf wiedersehen, and turned toward the door he had entered with such relief only moments before. Digging deep, he looked up at the stars and embarked on an unthinkable but eerily familiar journey.

Two months later, the elderly couple was proven right. On April 29, 1945, Allied Forces liberated the prisoners of Stalag VII-A. Steve was indeed among those celebrating freedom, this time permanently, 268 days after parachuting into enemy hands. The night sky had faithfully guided his return to captivity, unnoticed, just as it had his escape.

Soon after his liberation, Steve boarded a military transport plane headed stateside, this time in the passenger compartment. Having defied long odds against his survival, he was now laser-focused on putting behind him the traumas of his incarceration and manifesting the future he had dreamed of from behind barbed wire.

Two years later, he would marry my mother, Doris. I became the firstborn. My brother, Tom, and sister, Stefanie, would follow.

Steve’s life spanned what is rightly called the Greatest Generation. In many ways, he personified it. When Hitler was raging in the European theater, Steve was crewing missions over German territory until bailing out of a crashing B-17. When Khrushchev was shipping nuclear weapons to Cuba, Steve was airborne daily over the Florida Straits in a B-52, armed with intercontinental ballistic missiles and awaiting the order to launch. And when the Apollo 11 crew kept President Kennedy’s promise and took one giant leap for mankind, Steve was jubilantly trading back slaps with his fellow Saturn V rocket engineers inside the Kennedy Space Center.

Each time, looking to the sky and offering thanks.

As the years marched by, he became blessed with a growing family. He was over the now-proverbial moon when my daughter Valerie became his first grandchild. Several years later, he and Doris headed to Kauai, where Steve’s grandson/Tom’s son Avalon was to be born. The elderly couple was overcome by the joyous event and, after fully embracing the day’s bliss, opted for a well-deserved early bedtime.

Later that night, during those balmy and serene hours before sunrise all Hawaiians know so well, Steve stirred and wandered outside. The heavens were extraordinarily clear, no moon, the constellations bright, reminiscent of another such night, now 60 years past, but never forgotten. He lay down on the soft, cool, sweet-smelling grass.

After first light, my brother Tom arose, weary but deeply emotional from the birth of his son. Before making breakfast for the family, he strolled outside to check on his orchids. There, he found our father Steve, lying peacefully on the lawn, without a pulse, but with a broad smile on his face and a gaze gently fixed upon the sky he had always loved.

You must be logged in to post a comment.