My grandmother Kathy Cota passed away a year ago, in June just before the 100th celebration of what her father put together as a last-minute show to bring people together in 1924. My great-grandfather Juan Cota started what would become Old Spanish Days Fiesta to unite the town, to share the beauty of Santa Barbara, and to welcome visitors with pride and joy.

This year, as Fiesta began again, the weight of my grandmother’s absence felt even heavier. Not just because she’s gone, but because what she stood for, what she built, what she danced for is disappearing, too.

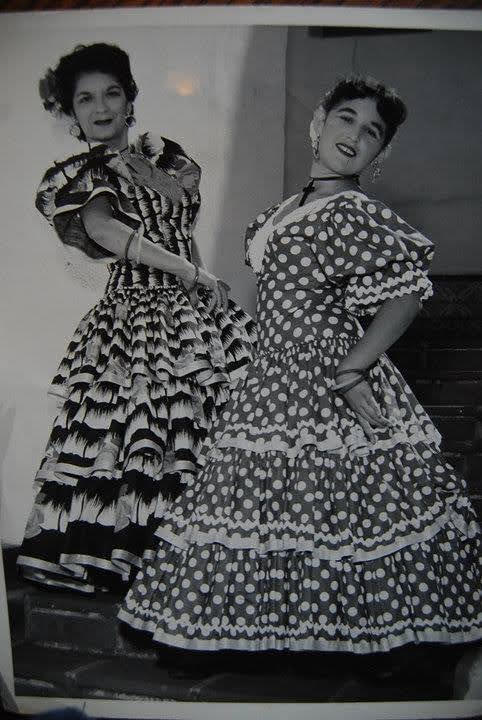

My family didn’t just participate in Fiesta — we helped create it. Juan Cota was called “Mr. Fiesta,” a true Californio, and the city honored him for preserving the dances, songs, and stories of Santa Barbara’s roots. His passion lived on through my grandmother Kathy, who carried the tradition with grace, founding Danza De Cota and keeping the flame alive for multiple generations of children who grew up in Santa Barbara dancing under the stars at Noches de Ronda and La Fiesta Pequeña.

For us, Fiesta was never a performance. It was never a costume. It was our lived identity — our gift to the city, and our way of gathering community around beauty and pride.

But this year, like so many in recent memory, something feels terribly broken.

The Fiesta I grew up with was a landscape cascading across the American Riviera — a joyful, inclusive, locally led celebration that is now being swallowed by something else: politics, favoritism, exclusion, and a growing disconnect between the organization and the very community that created it.

Ask any dancer or dance family participating this year: There is no support for the parents of these precious children. Kids rehearse and dedicate themselves all year to perform for free, while the Old Spanish Days organization reaps the cultural capital and financial gain. Families spend week after week paying for classes, often multiple ones, buying hand-crafted shoes, accessories, materials for costumes, paying dressmakers, building storage for outfits and props. These aren’t minor expenses. They come from a place of passion and pride, but it’s a quiet sacrifice, one that few on the outside truly understand.

Unless you’ve danced yourself, unless you’ve sweated under the weight of a traje de flamenca or twirled in the dark beneath glowing lights, you may never fully understand what’s being given.

Unfortunately, it now feels like if you’re not part of the “in crowd,” you’re expendable. It’s gatekeeping masked as tradition. Those who built Fiesta with their bodies, their time, and their culture are now being told: “You’re lucky to be here.” But it was our voices, our dances, and our stories that made this celebration meaningful in the first place.

And now, that meaning is being erased. Whitewashed. Repackaged for photo ops and old men in embroidered jackets playing dress-up as Spaniards or Mexicans, eating cold beans and tomato-sauced instant rice, while Indigenous and Chicano community members are sidelined — or silenced altogether. Our heritage is cast into the corners, only pulled out when entertainment is due.

There are members of the Chumash and Chicano communities who’ve raised these concerns with grace and clarity. At recent community panels, I’ve heard brave voices express what so many of us feel: This is no longer a celebration of our heritage — it’s a simulation of it. A party thrown by those with power, rather than with purpose.

I’m writing this not to tear down but to wake up.

Fiesta is still beloved by many, and it can be redeemed. But we cannot redeem it by pretending nothing is wrong.

We need transparency. We need community-led leadership, not just a line of El Presidentes on parade. We need real inclusion of Chumash stories, not just romanticized Mission imagery that continues to erase colonization’s brutality.

And most of all, we need support for the dancers who are the heart of this celebration. Not lip service. Not a ribbon or a thank you from a podium. But real investment. The kind that recognizes that the glory belongs not to those who “speak on behalf of,” but to those who do for.

My grandmother Kathy Cota gave her life to these traditions. She taught so many how to dance, how to love our culture, and how to serve our city with dignity, always with class, always with genuine love in her heart. Her loss left a wound in our family. But also a fire in me.

I still believe in Fiesta.

But I believe in the one we used to know. The one where the mercados lit up the night, where music and laughter spilled into the streets until 10 p.m., where children spun in bright dresses among confetti and sore feet and felt seen, valued, and truly celebrated.

The one built by hands like my grandmother’s and just a few more like hers.

We are still here.

But we will not be silent.

If Old Spanish Days wants to continue to honor its 100-year legacy, it must remember who made it sacred.

Because we weren’t just participants.

We were Fiesta.

You must be logged in to post a comment.