Santa Barbara Sparks California’s Agave Explosion

Meet Your Neighbors Who Are Leading the

Golden State’s Expanding Agave Industry

By Matt Kettmann | Photos by Macduff Everton

August 7, 2025

California’s agave industry is exploding right now, expanding from just a couple dozen acres a few years ago to more than 1,000 acres today, with much more on the way. Though there are some larger farms, like the one that hugs Interstate 5 just west of Fresno, the vast majority of the plants — most famously turned into tequila and mezcal in Mexico, yet also valued for food, fiber, fuel, and more — are dispersed across more than 300 smaller properties statewide. Agave intended for commercial usage now grows in at least 32 of the state’s 58 counties.

Santa Barbara County lit an early spark under this trend, as I first discovered in my January 2019 cover story “The Great Agave Experiment” about the first agave harvests at Rancho La Paloma on the Gaviota Coast. Earlier this year, while reporting a story on the industry’s growth — and its growing pains — I was reminded that Santa Barbara remains a critical force behind the Golden State’s agave movement. In fact, the California Agave Symposium, which has been held in Davis since it started in 2022, will come here next spring.

Over the past couple of months, photographer Macduff Everton and I visited numerous farms growing agave across the South Coast alone, from the craggy mountains over Carpinteria to the canyons above San Roque to the valleys behind Goleta. Our search was far from comprehensive — we didn’t even hit the Santa Ynez Valley, where at least a half dozen plantings are underway. (I did, however, talk to Cuyama’s first grower.)

Reflecting what’s happening across California — and, to a lesser extent, in places such as Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona — these emerging enthusiasts are electric about the promise of agave. They see these hardy, easy-to-grow plants, which are related to asparagus and come in more than 200 varieties, as a potential cure for the troubling environmental and economic climates that ail us.

Agave serves as an excellent firebreak for the wildfire-ravaged West Coast; its waterlogged piñas (the pineapple-like core) and panka (the sword-like leaves) are able to stop flames in their tracks. Yet it requires very little water to grow, especially when compared to popular hillside, dryland crops such as avocados and lemons. As an added bonus, it naturally replicates itself with rapid regularity in the form of pups, seeds, and bulbils. And when turned into alcohol — or syrup or shirts or even surfboards — agave can be a very profitable enterprise.

But Santa Barbara’s growers are also grappling with the nascent industry’s early issues. Are the dominantly planted varieties of tequilana and espadín — the former used for tequila in Mexico, the latter the main source of mezcal — right for California, or are more obscure varieties better suited? This gives an intellectually intriguing though at times troubling air of mystery to it all — no one knows exactly what they’re doing, from the planting to the processing.

Add to that claims of cultural appropriation, so much so that two separate agave departments now exist at UC Davis, one more focused on commercialization, the other more sensitive to such impacts. Then came complaints that the creation of a statewide commission moved too fast and too silently for some folks, causing the industry’s first political kerfuffle earlier this year. (That seems tabled for now.)

The biggest problem, no matter where you sit on any of these issues, is what may soon come if there’s nowhere to process the maturing plants when they’re ready. To date, the harvests — which come anywhere from three years to more than a decade after planting, depending on variety, site, and, well, no one exactly knows — have weighed in at a couple of tons here and there.

That can be made into a few hundred bottles of California agave spirit, which is the legal name, as Mexico protects tequila and mezcal. (Some suggest “Calgave.”) Given the scarcity to date, only three distilleries have any sustained experience working with the plants, which must be cooked, mashed, and fermented before being distilled.

But come 2028, or even earlier, there might suddenly be 30,000 tons of agave ready to pick. So, the sprint is on to develop the industry’s processing potential, and that race will need multiple winners building multiple facilities in order for California’s earliest agave growers to avoid a major glut.

Sitting in the middle of all of this is Craig Reynolds, who started growing agave in Yolo County a decade ago, spearheaded the creation of the California Agave Council, and led efforts to pass widely applauded protective laws and create that controversial commission. He’s stepping back to let new voices lead, but Reynolds will forever be the godfather of the California agave, cherished by many and suspect to others.

“What I hope for is a wide variety of different experiences and stories being told,” said Reynolds to me over the phone earlier this year, right after agreeing that Santa Barbara could be the state’s agave capital. “My own particular hope is to see agave being scaled as a significant crop to keep farmland in production, to conserve a significant amount of water, to reduce carbon in the atmosphere significantly, and to provide a significant number of jobs. I want to see a vibrant agave industry that can go beyond distilled spirits and into food, fiber, biofuels — the full use of the plant —and do it in an environmentally sustainable way that Mexico could learn from.”

Tapping the Terroir

If Reynolds is the bureaucratic visionary of California agave, Doug Richardson would be the botanical one. Once known as “The Banana Man” for the many types of that fruit he grew near La Conchita in the 1980s and ’90s, Richardson started importing, growing, and selling agave more than a decade ago. His plants started most of the Santa Barbara farms and many others across California and the Southwest.

After selling plenty of tequilana and espadín, he’s become wary of those varieties, believing other agaves are better suited for California microclimates, which are generally cooler than Mexico. At his property in Casitas Springs — he left his longtime Carpinteria nursery about five years ago — Richardson grows more than 30 varieties of agave, from the smooth, spineless desmetiana to shark-skinned asperrima, which makes a celebrated mezcal called lamparillo.

“That’s my responsibility,” said Richardson, “to make these plants available because they have not been available in California.”

Jordie Ricigliano is a disciple of the diversity mission. With her husband, Luis Velazquez — who grew up five minutes from a tequila factory in Jalisco, but came to Santa Barbara for high school — she farms agave on four separate properties in Carpinteria, Goleta, and Los Olivos, with Hollister Ranch coming soon.

They became interested in agave after trips to Jalisco and Oaxaca about a decade ago, eventually propagating way too many plants on their windowsill in downtown Santa Barbara. The plant reminded Ricigliano of her career in wine, where the concept of terroir is king. Working on multiple properties with agave empowers their ongoing exploration.

“That’s our blessing in disguise,” said Ricigliano of not owning their own ranch. “It allows us to play with so many local soil types and landscape types, and also with ideas of what agave could be used for. We work with different properties that have different ambitions.”

At the ranch they farm in Carpinteria, Ricigliano and Velazquez — whose business is called Los Hijuelos, the Spanish name for the pups — grow about eight varieties, from familiar tequilana and will-be-massive mapisaga and arroqueño to a desert variety called durangensis and the marbled variety called marmorata that appears to be crawling away. “They look like dinosaurs,” said Velazquez, who’s also interested in varieties like shawii and parryi that are native to Baja and the American Southwest. “Parryi has a history of being fermented for thousands of years.”

Their agricultural enemies are snails, ants (because they farm mealy bugs in the plants), and gophers. “They’ll eat the whole head,” said Velazquez of the rodents, to which Ricigliano adds, “You won’t even know it until the whole plant falls over.”

Before we leave, they share a sip of their first-ever bottling, in which 12 plants were turned into 169 bottles by Shelter Distilling in Mammoth Lakes. “We don’t care if it’s good or bad — we just want it to be different,” said Ricigliano. “We can work on the good.”

They’re dedicated to determining which agave varieties taste distinctive where. “Is there another chapter in the agave story, like a really interesting expression that can come out of Santa Barbara County terroir or Northern California terroir?” pondered Ricigliano. “My early impression is that there is, but it’s too early to tell.”

Disaster to Distillation

The “aha” moment for many agave growers in Santa Barbara — particularly those in the Montecito and Carpinteria foothills — came after the one-two punch of the 2017 Thomas Fire and 2018 1/9 Debris Flow. That’s when Richardson and Montecito resident Berkeley “Augie” Johnson really started evangelizing about the plant’s benefits for the wildland interface.

“This was built on cataclysm, I like to say,” admitted Mark Peterson, who was drawn to the firefighting properties and low water needs of the plant. With his wife, Ané Diaz, they grow a half-dozen or so varieties across nearly a dozen acres at Rancho del Sol in the upper reaches of Montecito, literally looking down on the billionaires.

Though she was against the idea at first, Diaz — a former punk-rock singer whose dad moved her family to Florida while fleeing Venezuelan dictators in the 1980s — is now all in. She’s proud to have UC Davis monitoring their property’s temperatures, was an early member of the California Agave Council, and is actively planning next April’s California Agave Symposium in Santa Barbara. The original plants they bought from Richardson had mixed results, so they’re now raising their own pups, seeds, and bulbils in an onsite nursery.

“The beauty of this plant is how generous it is,” said Diaz, who shows me spoons, bags, and a leather-like fabric made from agave. “There’s going to be a renaissance that this plant creates. We’re enhancing the culture of California.”

Rancho del Sol may lead the state in the number of distillations so far. They’ve had four bottlings of California agave spirit so far, all handled by Shelter Distilling, whose co-owners live in Montecito. Diaz and Peterson are proud of their ensembles, in which multiple agave varieties go into the same bottling. The latest bottling lists six varieties, but Peterson is quick to assert, “It’s actually seven, but they couldn’t fit that on the label.”

The more they make, the more they learn. “We’re taking advantage of every bloom,” said Diaz. Wonders Peterson, “Can we capture the flavor of Montecito in a plant?”

In addition to Shelter in Mammoth and Venus Spirits in Santa Cruz, Ventura Spirits is the third company to have processed agave at a commercial scale in California. They’ve developed a few techniques over multiple batches, like soaking the bagasse — the fibrous mess that remains after the agave is mashed up — with hot water. “It contributes a really nice agave flavor,” said co-founder Anthony Caspary.

They’re investigating other parts of the plant, like the panka. “We couldn’t find anyone who’s done that,” said Henry Tarmy, another cofounder, of fermenting the leaves. The result is a slightly herbal, somewhat medicinal, even peppery booze — at the very least, something that could be added to a blend to add complexity.

They’ve also blended finished agave spirit with the thicker, sweeter, nonalcoholic agave syrup. “This is the first time we’ve tasted it,” said Caspary of the coffee-like, caramelly, vanilla-inflected product, which sits at about 20 percent alcohol. It’s not yet for sale, but Kahlúa lovers would dig it.

Processing Potential

There’s a step before making booze that doesn’t have to happen at a distillery. This is where Mark Hannah hopes to find a niche: by building a small processing facility on his property above San Roque where growers can have their plants crushed, cooked, or otherwise processed as needed before distillation or whatever comes next.

A developer from Chicago, Hannah moved to Santa Barbara during the pandemic, bought a former avocado ranch on the eastern bluff of Barger Canyon, and started searching for a new crop. “People have said that you don’t find agave; agave finds you,” said Hannah, whose friends erased his bad college memories of cheap tequila by taking him on a trip to Jalisco. “I was really inspired by visiting these different palenques. They really taught me a lot about the artisanal ways that tequila is produced and grown.”

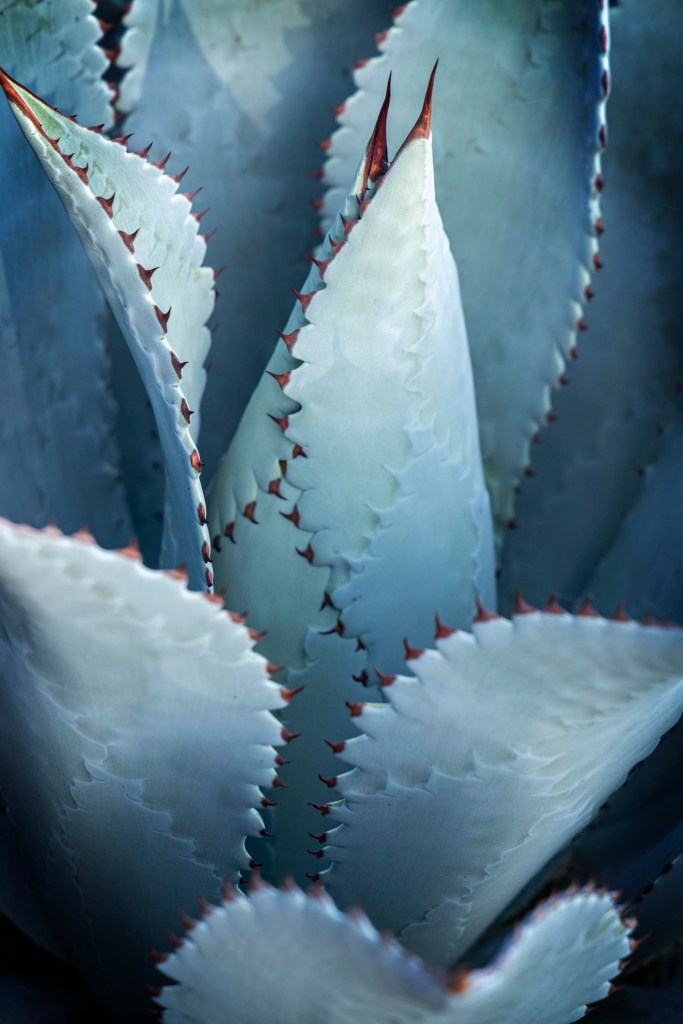

His property’s natural amphitheater made a great canvas for blue agaves, which glisten in the late afternoon sun. “I did that purposefully, like it was a painting, like a piece of art,” he said. “It’s such an iridescent plant.”

Beauty is just one of agave’s gifts. “There are a lot of downstream products that come from agaves,” said Hannah. “There’s an opportunity to come, whether people are harvesting the leaves or planning to distill or making furniture. We would love to be the processing facility for someone like Ryan Carr.”

After decades of managing vineyards, which he still does, winemaker Ryan Carr of Carr Winery added agave to his repertoire about six years ago, and now works with four properties from the other side of Barger Canyon to the Santa Ynez Valley. It’s been a massive learning curve, from realizing that potted plants underperform the pups to learning about the fermentation process, which is riddled with bad aromas, finicky yeasts, and volatile acidity. He learned the latter while working with Ian Cutler of Cutler’s Artisan Spirits on a batch that Hannah had roasted and mashed at his ranch.

“There’s just not enough access to people who know what’s going on with this stuff,” said Carr, who plans to distill future harvests at the new facility he’s building behind his winery on Salsipuedes Street. “It’s just getting started.”

Agave is giving Carr new eyes on grape growing and winemaking, which no longer seems so rigorous. “There is more opportunity for joy in the wine industry,” he said, because vines are soft, grapes are sugary, and everything is more pleasant the whole time. “This stuff, it pokes you, it pushes you. You’re constantly bleeding. I’ve got wounds all over my arms.”

When you cook it, the flavors are gritty and heavy, and then the fermentation gets weird. “The faster the fermentation, the better,” he said. “It’s the exact opposite of wine.”

But there is a light at the end of the long tunnel. “It’s so painful all the way through, and then you get this wonderful thing at the end,” said Carr, passing me a copa of his finished spirit.

Growing Education

At her ranch in the hills behind Summerland, Carolyn Chandler is both excited and cautious about the whole thing. “I’m a plant person, and I like the sustainability of it,” said Chandler, who put in more than 400 agave plants in 2018, replacing some of her avocados. “We’re all searching for the next crop around here. Avocados are not it.”

Her first harvest — which must happen within about six months after the plant shoots its stalk, or quiote — came way earlier than anticipated, and only involved a few plants. “I thought they’d all be harvested at once,” said Chandler, a longtime employee of the Land Trust for Santa Barbara County. “It still feels like this is a big experiment in California.”

Amid such mystery, there’s value in pursuing different farming strategies. At Rancho Esperanza off of Toro Canyon Park Road on the easternmost edge of the Montecito foothills, Ron Toft is going water-free on some blocks. “We dry planted and we’re not watering at all,” said Toft, who retired from running a school construction firm in Rancho Cucamonga 30 years ago, and moved to Montecito in 1985.

He now has about five acres of agave amidst the 40 acres of avocados on his ranch, and is planning to build a nursery in order to raise their own pups rather than buy more plants. “It’s so new, I don’t want to spend any money,” he said. “We don’t even know if we will ever sell one.”

He looks at all the avocados that cover the hills of his ranch, which are still a viable concern. “I don’t want to tear the trees out if they’re producing, but if this turns out to be a miracle plant, I’ll tear them out,” said Toft, whose agave fields look more like Oaxaca than anywhere else I’ve seen. “But who knows if I will ever see that? I’m 79!”

The agave tide is now crashing in the Cuyama Valley too, where a lifelong ocean aficionado named David Russian settled into the high-desert life by planting about 2,000 agaves a couple months ago. “I just put them in the ground, and they just started taking off,” said Russian, who’s worked in real estate, as a contractor, and as a boat builder. “I’m new to all of this. I didn’t realize that nobody had done agave planting in the Cuyama Valley.”

Like Toft, Russian is not a tequila drinker. “I actually despise it, to be honest with you,” he said, adding with a laugh, “I should have done whiskey!” But he’s fascinated by its appearance and its potential, despite the long hours and cost of irrigation equipment. “It’s hard work, but I’m finding myself wanting to put more in the ground,” said Russian. “It’s an obsession, almost. I really did it because I love the plant.”

A Better Future

Many of Santa Barbara’s agave growers are farming commercially for the first time, including Margo Redfern at Wanderment Farms, one of the most ambitious regenerative projects in the region.

Amid her olive trees, wine grapes, lavender, bananas, coffee, sapote, avocados, and vegetables are agaves, which she’s interplanted with corn, sunflower, squash, tomato, and cucumber. They were originally intended as a firebreak above a canyon that swoops down toward the greenhouses of Carpinteria, since her shrub-eating goats couldn’t compete with the hungry bears.

But the plants did well, so she got more interested. “You stick the agave in wherever, and it just grows,” said Redfern. “It’s super happy.”

She’s since invested in processing equipment, hoping to make some money from agave one day, like she does on her eggs and produce that she sells through The Farm Cart locally and at Erewhons in Los Angeles. “We are a commercial farm,” she said. “Profitability does matter.”

Meanwhile, agave is opening new doors for multigenerational farmers like Stan and Stephanie Giorgi, whose 78-acre ranch up Glen Annie Road has been in the family for nearly a century. It was a dairy before avocados and lemons took over, but eventually those weren’t working as well either.

“I saw the wheels coming off the bus,” said Stephanie, who’s been with her husband for 43 years. “Stan was increasing poundage, but we were making less money. And when you’re on a piece of property this long, you see the effects of soil degradation.”

Faced with increasingly less accessible and more expensive water plus tumultuous avocado and citrus markets, they decided to plant agaves in 2018. They didn’t know their property would become a model California agave farm, at least according to pioneer Craig Reynolds, who visited in 2021. “We didn’t know what we had at that point,” said Stan of his ocean-view agaves. That’s emboldened Stephanie, who explained, “I really do believe Santa Barbara to be the premier area.”

There are about three acres in agave now, amounting to about 3,000 or so plants, much coming from the persistently popping pups. “Every time you buy an avocado tree, it’s $35 to $40,” said Stan. “With the pups, it’s basically free.”

Like at other ranches, a random number of their agave sprouted far earlier than expected, so they sent the cleaned-up piñas to Ventura Spirits. Caspary and Tarmy turned it into a bottling called Tecolotito, which is one of the better batches in the state’s history so far, at least from what I’ve tried. If that can continue, agave would be a more profitable crop than avocados.

Agave set the Giorgis on an even deeper sustainability path. After watching The Biggest Little Farm and reading soil health books years ago, they stopped spraying their orchards and tuned into regenerative farming.

“A certain part of me thought, ‘Wow this is a huge change,’ but I’m excited about all the birds and insects I see,” said Stan, a fourth-generation farmer who wears baggy overalls without a hint of irony. “Every night we come out here, there’s an owl on that raptor perch.”

Stephanie finds the new direction life-affirming. “The cool thing is that, at 60 years old, we are making the life of our choosing,” she said, explaining that most multigenerational farming families are reluctant to change.

“You have to be willing to put down what’s familiar to tune into what is new,” she said. “We have the vision to invest in ourselves and to live a life in tune with the soil. We want to be able to walk around and be proud of what we’re doing.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.