I read the story of the Summerland fete for local charity in the Independent (Sept. 25) with grim disquiet. Pardon me if I am not grateful for the beneficence of rich people. Especially when I believe that the haut monde of Montecito, which includes British royalty, has done more damage to Santa Barbara than they could ever undo with a little philanthropy.

Santa Barbara is in a remarkable and critical period in its history. The colossal limelight focused on the city and atmosphere of extreme wealth and celebrity has contributed to undermining every kind of social and economic foundation that has been built up in Santa Barbara for generations. Santa Barbara has gone through many phases and mutations as a community but none so destructive as the present era.

There have been several episodes of national and international renown. Santa Barbara was promoted in the late 1800s as a resort and retreat, and this helped bring about the time of the enormous hotels. A little respite followed but prestige came again with the creation of the big Montecito estates and emigration of big money from Chicago and the East.

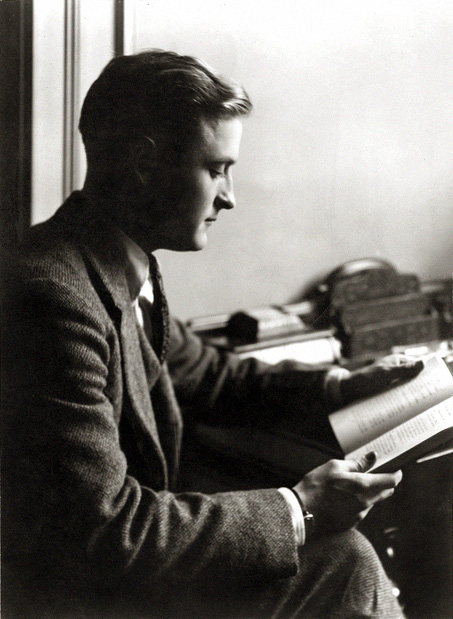

Through the 1920s Santa Barbara was on the circuit of the wealthy, a stopping-off place for money and glamour. It should be of lasting and particular interest for locals to know that Santa Barbara is mentioned in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel The Great Gatsby. Fitzgerald, the author so famously fascinated by the rich, spent only a few words on Santa Barbara, but what he said is undisguised contempt. A place where “people played polo and were rich together.” Curiously, Fitzgerlad had never been in Santa Barbara at that time, he simply knew of the city by reputation and through some friends.

The Depression of the 1930s brought a blissful eclipse and national amnesia for Santa Barbara. I grew up Santa Barbara in the 1950s and ’60s, a period when no one outside of town had heard of the place. There was a stable working class and middle income group; it was a diverse and harmonious community.

Bobby Hyde bought property and created his Mountain Drive subculture. There was a real and affordable arts community. Artists like my friend Tom Huston lived in their studios in the Fithian Building on State Street through the 1980s. The artist Michael Gonzales lived and worked there and one day, in all his good humor, invented the local Solstice Parade and celebration. Now an annual event it must have made a zillion dollars for the local tourist industry. But Gonzales could no more afford a space in the Fithian Building these days than he could afford to live anywhere in Santa Barbara.

There is no such thing as an artistic bohemia in Santa Barbara any longer. Now we have the Santa Barbara International Film Festival, a well-funded Montecito travesty with the primary function of persuading the wealthy that Santa Barbara is a great place to come and drive their Range Rovers.

By the 1990s Santa Barbara was being rediscovered. History was repeating itself for the worse, much worse. When the son of a king moves to Santa Barbara the eyes of property owners light up with dollar signs and the conviction that they are now worth more. Landlords applaud and renters live in fear.

Two friends of mine left Santa Barbara recently. The lived here for decades, raised their daughters, and worked important jobs with City College and the Westside Clinic. They expected to retire in Santa Barbara, but their landlord, in the frenzied speculative atmosphere, was seduced by the ineluctable force of dollars and the property was sold from under them.

Santa Barbara acquires more celebrities all the time but loses the people who have made the town. I grew up with kids who were related to the street names in Santa Barbara; the roots were deep and lasting. Santa Barbara likes remembering one aspect of its history with the Fiesta every year, but Santa Barbara is increasingly a town without a history. It is all ripped apart and scattered in a tornado of money.

At their party, did the Montecito elite ask the employees of the police and fire departments if they live in Santa Barbara? The fact that many essential workers in Santa Barbara do not live in the city is well-known and a source of concern. It creates a kind of civic vulnerability.

I worked on a medical unit at Cottage Hospital for many years, and one third of my coworkers commuted daily from the North County, Ventura, or Oxnard. I think that is a roughly accurate statistic for Cottage Hospital workers as a whole. I always thought of Cottage as a kind of microcosm for Santa Barbara. If the hospital was on unsure footing, the whole community was unstable.

“If I didn’t live where I live now, I couldn’t live in Santa Barbara.” That is the lament of the long-term renter. I have heard it many times. And I am one of them. I have lived in a very small and affordable place for many years. My landlord is elderly, and I don’t know how much time I have left here. The fate of the Edgerly Apartments, where I hoped I might move, is unknown at this time. Other senior housing is uncertain. My next address may be mobile, i.e., my car.

No doubt there are many factors and forces that have been at work in changing Santa Barbara. But I blame, I think with sufficient reason, the cash mania and super-rich celebrity culture that has a choke-hold on the city. Local government has failed across a variety of issues for over 20 years.

If I sound bitter, it’s because I am bitter. I have this in common with a very large class of Santa Barbarans who feel betrayed by a city they have given their lives to. I have been an exemplary citizen of my home town and active in local politics for a lifetime. But politics in Santa Barbara has taught me something very cruel: Money always wins.