Going Green: The Virtues of City Trees

Street trees are key to pedestrian comfort and urban livability. In addition to offering shade, they reduce ambient temperatures in hot weather, absorb rainwater and tailpipe emissions, provide ultraviolet protection, and limit the impact of storm winds.

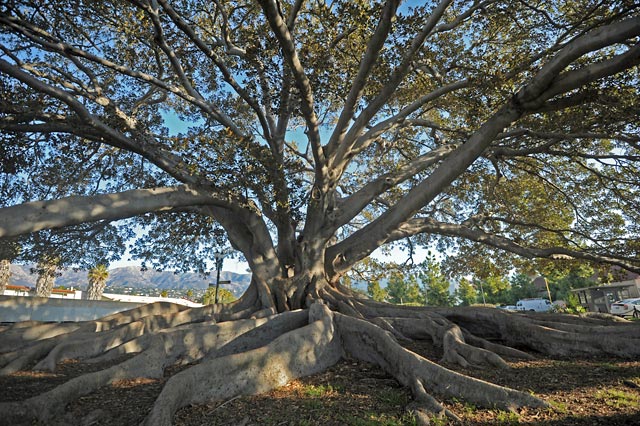

Many of our cities are experiencing heat waves, which, if not directly attributable to climate change, are boosted in frequency and intensity by our gluttonous spewing of greenhouse-gas emissions into the atmosphere. Measurements of ambient temperatures taken on exposed versus tree-canopied streets around the United States document temperature differentials ranging from 10-15 degrees Fahrenheit between the two. The difference can be potent when temperatures hit triple digits. Proper tree cover on urban streets can virtually offset the phenomenon called the “urban heat island” effect. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the cooling effect of a single healthy tree “is equivalent to 10 room-size air conditioners operating 20 hours a day.” (In Santa Barbara, our abundant and beautiful palm trees, unfortunately, do not provide the environmental benefits that broad canopy trees do.)

A properly shaded neighborhood is said to require 15-35 percent less air conditioning than a treeless one. Climate change begets air conditioning, which begets carbon pollution, which begets more climate change. Denser urban canopies could help short-circuit this vicious circle.

Even more impressive, however, is the astoundingly large role that trees perform as a carbon sink. In what economists call an “ecosystem service,” trees are unsurpassed in their capacity to gobble up CO2. And urban trees, located as they are in close proximity to roadways, are 10 times more effective than more distant vegetation at hijacking car exhaust before it hits the stratosphere.

When an inch of rain falls on a tree, the first 30 percent of the precipitation is typically absorbed directly by the leaves and never even touches the ground. Once the leaves are saturated, up to 30 percent more of the rain seeps into the soil, made more porous by the tree’s root structure. This root structure then pulls the water back up into the tree, from which it is eventually transpired back into the air. The process allows a mature tree to absorb about half an inch of water from every rainfall.

A comprehensive study in Portland, Oregon, called “Trees in the City” concluded that each mature tree was responsible for almost $20,000 in increased real estate value. In the aggregate, this adds $15.3 million to annual property-tax revenues for the city, while the city pays $1.28 million each year for tree planting and maintenance, resulting in a payoff of almost 12 to one.

Santa Barbara Beautiful and our area parks departments do a commendable job planting trees on our local streets. An equal commitment to keep them alive, however, is not always present. Since street trees may be the best investment a city can make, we all need to pay attention to them and help keep them healthy so that they can continue to provide their full array of benefits.