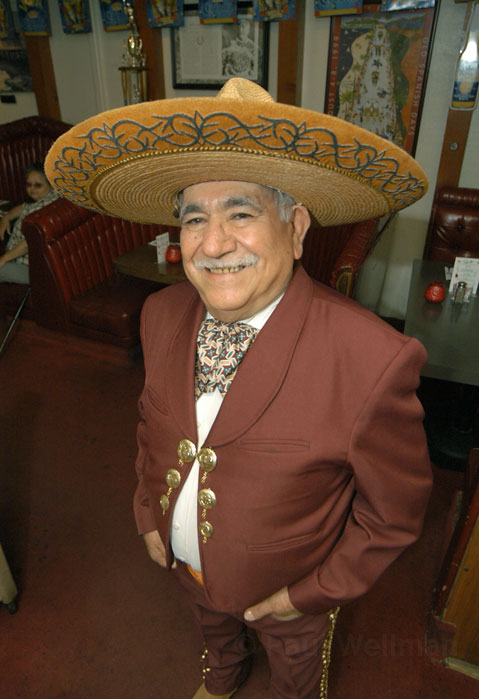

I remember that Fiesta when Pascual rode a horse through his restaurant at 30 E. Victoria, banging his head on a crossbeam and nearly trampling a mariachi singer. I was at the bar, my back to the hand-carved sign that read, “Good Thing We Don’t Drink,” defending a Corona in the crunch of revelers showered in cascarones. Pascual made his entrance in his cream-colored, three-piece mariachi suit, wearing his signature sombrero grande. Fueled by some extra Hornitos, he soon grasped the obvious: It’s one thing to ride a stallion onto a tiled floor in a packed tavern—and quite another to turn it around.

Antonio Perez, Pascual’s first dishwasher and trusted compadre, was there that afternoon. Back in ’68, they had gone on a 10-week road spree in Mexico in Antonio’s aqua blue Thunderbird. Now Antonio was sitting in the back of the restaurant in a red plastic booth, one of those art deco jobs hauled over from the old Pascual’s on Carrillo Street. He can’t believe his eyes as horse and rider skid by the jukebox on the drink-slick floor. “Pascual was a cowboy when he was young, but restaurants are dangerous,” he advised me with a straight face. “The terrain is not made for horses.”

At that moment Sandy Romero, the waitress everyone called Wonder Woman, was talking to an insurance agent—a Fiesta celebrant who just happened to provide Pascual’s liability policy—when the startled animal began to lose its footing. “That’s when that horse kicked Booth # 6, which was full of people!” she said. “This guy’s jaw dropped and I heard him say, ‘Please tell me that just didn’t happen.’”

Pascual Gamboa, the 80-year old restaurateur who died of heart disease earlier this month, was the last of the Santa Barbara old-timers, that breed of freewheeling originals in the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s who named their restaurants Harry’s, Cattleman’s, Mom’s, and Arnoldi’s. A small man known for his grace and kindness, Pascual was born in 1930 on El Carrizo, a hardscrabble ranch in the Mexican state of Jalisco. His father died in his early 40s of a heart attack. Pascual grew up with 15 brothers and sisters at the adobe homestead. As a teenager, he strapped salt blocks to horses and dropped them off along the dry riverbed of the Río Bolaños to keep the family cattle alive. In 1952, as he later told me, he “jumped the border, looking for a better life.” It was the night of July 4th and young Pascual was on his way to Sacramento, hoping for a laborer’s job on the Southern Pacific Railroad. When he crossed the river into the U.S.A., the sky was full of fireworks.

After a few years of railroad work and odd jobs, Pascual was snagged by la migra and deported. He tried again, this time landing in Santa Barbara where he got a dishwashing job at the San Ysidro Ranch. Before long, he was promoted to fry cook. Later on, he’d become a full-fledged chef, honored businessman and El Presidente of Old Spanish Days. Along the way he picked up his green card.

I met Pascual in the early 80’s through Rogelio Trujillo, the local landscaper and social activist from Zacatecas, Mexico, whose periodic run-ins with the cops made him a legend in some circles. By then, Pascual had opened his own place in the old Carrillo Hotel, across from the Greyhound bus station. The eatery was famous for “wet sandwiches,” especially Italian sausage with Pascual’s homemade Mexican salsa, and the lines at lunchtime went out the door and down Carrillo. Back then, according to Antonio Perez, down-on-their-luck bus riders would cross the street hoping for free food. “Pascual wouldn’t let them beg inside, but he always wrapped up something for them to take away.”

In those days Pascual didn’t have a full liquor license. But Clarita, his feisty waitress, bookkeeper, and lifetime partner, sometimes made wine margaritas that tasted like the real thing. Clarita, who is the mother of Gary Gamboa, Pascual’s only child, is now 89 and she remembers those customized concoctions. “I used fresh pineapple, an olive, a rim of salt, and whatever else I felt like putting in that day,” she recalled with a smile. “The margaritas cost $1.75, and we made a lot of money.”

When Pascual lost his Carrillo lease in 1987, he reopened the popular restaurant on Victoria. Gary, a road engineer for the county, worked there weekday mornings before classes at San Marcos High School, earning $20 a week as a janitor. He recalls his father arriving at 6 a.m. and firing up their only oven with fresh tri-tip and turkey for the lunch crowd of “tradesmen, lawyers, politicians, and who knows else” who’d start wandering in by 11:30 a.m. “My father trained me to have a great work ethic,” he said.

Breakfast at the new venue was served 365 days a year, starting at 8 a.m. The staff called Pascual “the Energizer Bunny” because he seemed to be everywhere, even singing trademark mariachi songs like “El Rey” and “Volver” after the bar closed at 2 a.m. If customers managed to return for an early breakfast the next morning, chances were they’d see him again—maybe not singing, but still smiling. “He treated the place like our living room at home,” Gary told me. “If you walked in having a bad day, you’d always walk out a little happier.”

Pascual was a soft touch. Longtime bartender Jon Reid remembers a stack of IOUs behind the cash register and how a business partner shook his head when another free meal went out the door. The restaurant was always a success, Reid told me, “but Pascual was in business for the people, not the bottom line.” Gary agreed. He said his father knew what it was like to be hungry, and he never forgot where he came from. Gary remembers a bothersome regular in the Carrillo restaurant, “an older gentleman who was poor and smelly,” and the customers who wanted to “shoo him away.” Pascual wouldn’t hear of it and always let the man sit at the bar and nurse his beer. Wonder Woman recalls another time, the morning on Victoria when she warned Pascual that a rough-looking drifter was at the back door wanting to use the toilet. “Dejale en paz,” Pascual instructed her. “Leave him alone.” Then, as the visitor proceeded to take a sponge bath in the men’s room, Pascual told Tony, the cook, to put together a burrito. Pascual wrapped the hot food in aluminum foil and gave it to Wonder Woman to deliver. “Es bueno,” Pascual said.

So much to remember: Summer Solstice, the biggest money maker of the year; St. Patrick’s Day, with Pascual in a green t-shirt that said “Kiss Me, I’m Irish”; and Cinco de Mayo, with those Budweiser Girls in their bathing suits handing out key chains and vying for pictures with Pascual.

But I have a quieter, more generalized memory: I am in Booth #11 by the window on East Victoria, as usual, eating chile verde with large chunks of fresh pork and three kinds of chile. Rogelio Trujillo and screenwriter Duffy Hecht are there, along with Robert Landheer, the criminal defense lawyer, and Paul Sugino and Will Hastings from the Legal Defense Center. Will has tipped off Sunset Magazine about Pascual’s fish tacos, and now the restaurant’s recipe is on the cover. For his part, Rogelio has convinced Pascual to donate cases of chicken or tri-tip for another homeless fundraiser, and we are all going over plans for the next barbeque. The place is loud, as always, full of firefighters, engineers, city inspectors, and other regulars.

I can see Pascual come down the stairs from the apartment he built above the bar, the one without a permit. I watch him go table to table, slowly, shaking hands and smiling. At one point he comes to the rescue of my daughter Cáitrín, who’s fending off a too-forward customer. It’s her first job as a waitress. At 16, she’s too young to carry alcoholic drinks to the table—why he agreed to hire her I’ll never know—and Pascual is helping her out. Our table is full of food and there’s laughter in the air. Everybody’s home.

Visitation for Pascual Gamboa will be Friday, September 24, from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. at Welch-Ryce-Haider on 15 East Sola Street, followed by recitation of the rosary in the evening. The funeral mass will be held at 10 a.m. Saturday, September 25, at Our Lady of Sorrows Church, 21 East Sola Street. The burial will follow at Calvary Cemetery on Hope Avenue, followed by a reception with live mariachi music at Woody’s Roundup Bar & Grill at Earl Warren Show Grounds.