Between global expeditions in search of precious gems, Santa Barbara gem trader Dana Schorr would regale friends with tales from Tanzania, Tibet, and points beyond, where village miners armed with picks, shovels, and sieves still seek precious jewels in muddy pits, as they have since biblical times.

Schorr specialized in “colored stones” — rubies, sapphires, emeralds, and lesser-known gemstones. According to the Wall Street Journal, the colored-gem trade is dominated by adventurers like Schorr, “who wander some of the globe’s most dangerous and underdeveloped places in search of treasure.”

Schorr grew up in Santa Barbara and attended San Marcos High. Dark eyes flashing and a black mane of hair tumbling over his shoulders, he abandoned school to follow his own path in the early 1970s.

Paul Broeker met Schorr in 1971: “My wife, Debby Lipp, and I had hopes of starting a restaurant on State Street. Dana was organizing a Community Union and had space in the same building. He was 19, totally uninterested in school or any other institution. He lived wild and free and wanted to do truly radical organizing.”

Schorr, Broeker, and Lipp found an old house on lower Anacapa and moved in with a raggle-taggle band of comrades. They christened their “collective” Anacapa House. With its gathered-food dinners, earnest household meetings, and Big Mike the Biker sleeping in a panel truck in the driveway, Anacapa House became Schorr’s second family.

Anacapa House housemate Karen Madsen remembered: “I was dazzled by my handsome, fiercely intelligent, irreverent, and wickedly funny roommate at Anacapa House. Dana and I became romantically involved. We split up a year later but remained close friends for the next 40 years.”

At the time, I was an earnest, young journalist for a new alternative newspaper, the Santa Barbara News & Review. I also lived at Anacapa House, out back in the unheated shed beyond Big Mike’s truck. Schorr, then a radical printer, never tired of offering outspoken opinions about how to keep the paper true to its progressive values. (The SBN&R decades later merged with The Weekly to create The Santa Barbara Independent.)

He was working with Peter Katoff at Sabot Press, named for fed-up workers who used their wooden shoes, or sabots, to jam hated mill machinery during the early Industrial Revolution. Their shop was unionized under the International Workers of the World (“Wobblies”).

With his unmistakable, husky laugh and passions for storytelling and dancing until dawn, Schorr could be the life of any party. At the same time, he was equally capable of hassling all he disagreed with, foe, family, or friend. “Dana was kind, intelligent, generous, and funny,” Katoff said, “but he was often an obnoxious pain in the ass, a title he was proud of.”

After a visit to the Tucson Gem & Mineral Show in 1980, Schorr fell in love with gemstones. He took a correspondence course in gemology and began traveling the world in search of jewels, reinventing himself as an international entrepreneur. Schorr’s penchant for persuasiveness, honed as a radical organizer, served him well in his new profession, especially after the largely unregulated colored-gem trade became an ethical target.

During a trip to Bangkok in the mid-1980s, he befriended gemologist and writer Richard Hughes. Like Schorr, Hughes was brilliant and entirely self-taught. Together, they went on gem-hunting expeditions worthy of Indiana Jones — to Burma’s jade and ruby mines and to Madagascar, Tibet, and Africa’s Great Rift Valley, from Mozambique to Ethiopia.

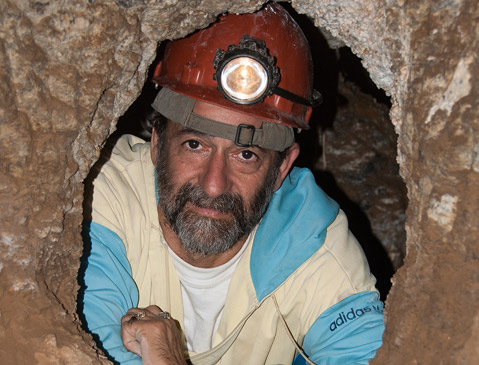

“Dana was a fearless traveler, who had no qualms about descending deep into mines, nor walking to the edge of great precipices,” Hughes wrote. “His questioning of others often created discomfort, because it forced them to reexamine ideas that they had previously accepted blindly.”

In the late 1990s, critics began to raise concerns that colored gems might be like “blood diamonds,” tainted by child labor or links to terrorists. Schorr acknowledged problems but took a contrary view. With close ties to artisanal miners, especially in Tanzania, Schorr said top-down “solutions” would devastate small miners, gem cutters, and traders, most based in the developing world.

Since only large corporations could afford the imposition of traceability and other requirements, Schorr feared that “fair trade” regulation would turn independent miners into “employees” and destroy the independent colored-gem trading network. At a conference in London in late 2014, Schorr made his case before a packed audience of gem professionals, including strong human rights and fair-trade advocates. Schorr effectively brought artisanal miners’ perspectives to the table, arguing that first-world organizations needed to improve labor and marketing practices at home instead of imposing rules abroad. The hot debate about ethics continues within the colored-gem trade.

Schorr was not simply a contrarian. He could use his multilingual charm to get people talking across cultural and linguistic barriers. His longtime girlfriend Cheryle Carmitchel Robertson remembered how he once skirted language barriers in Zanzibar: “The bartender spoke only Swahili, we had one Swedish guy and a German couple who barely spoke English, and in about 15 minutes Dana had everyone talking as he translated for each of them.”

As decades passed, and his flowing mane became a Jean-Luc Picard pate, Schorr showed no signs of slowing down. Before his London presentation, Schorr took his mother, Emmy, on a trip to Machu Picchu in Peru. Between gem expeditions, he was active in neighborhood politics and the Santa Barbara Jazz Society.

Schorr suffered a heart attack at his Santa Barbara home this past summer. Social media exploded with tributes, prayers, and memories from around the world. He died peacefully on August 5, with family at his bedside. Schorr was 63.

On September 1, Schorr’s Santa Barbara friends held a memorial roast at SOhO Restaurant & Music Club, the same State Street site where Schorr had worked as a community organizer in the 1970s. “Dana was there for me during the best and worst of times,” recalled Karen Madsen, from Anacapa House. “He was a true friend.”