When the young Palestinian poet Elias Hanna landed in Isla Vista, it was during a time of ferment, an era when UCSB students hung posters of a moon-faced Mao above their beds. Out on the streets, amid the tear gas fumes the smoke of the burning bank and the bullets, we witnessed poets actually legislating. And being acknowledged. After Santa Barbara’s oil spill, one morning Isla Vista awoke to copies of Gary Snyder’s guerilla attack on the carbon economy. His “Smokey the Bear Sutra” had mysteriously materialized, tacked to every telephone pole. The poem’s parenthetical last line still serves as its DNA: “(may be reproduced free forever).”

A few of the Maoists had chosen the campus because of its proximity to mountainous areas where they dreamed of fading back into the hills to form base camps for staging guerilla operations. These students, though, studied beside others who suffered from another kind of poetry. We cultivated a smug disdain toward those who would sully their spirits in dealing with any problem on its own level — tomato, to-mah-to. Sitting atop our tatami mats, sipping green tea, we were more taken with certain Tang Dynasty poets than with Mao. We especially admired one wine-sodden fellow who’d drowned in a lake while attempting to embrace the full moon’s reflection. Like him, we were fond of mountains. Like him, we imagined that we were hermits hidden among craggy peaks. That across hollow gorges, tones from our flutes and zithers pierced the mists. That our spirits and the inner spirits of mountains and rivers communed in luminous silence. That detecting the tones of our zithers and flutes echoing through the grottoes, deer flocked to us, licking pine nuts from the palms of our hands, rubbing their necks against the trunks of fragrant pines, lisping to us in their mother tongue.

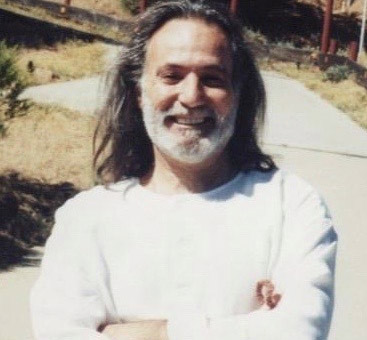

Being a poet, when Elias arrived he fell in with us. And he taught us the poetry of simplicity, the poetry of all things. Whereas our orientation was more aesthetic, he, as his names suggest, was tangled up in God, and so mysteriously mixed in grand portions of love with his pragmatism. The little details. The ingredients in his mother’s falafel recipe. The love and quality he mixed into each falafel that emerged from his kitchen at Baba’s Falafels (now Freebirds). The shack had previously been a juice stand named Eden, where itinerant sadhus had stopped in to sup. So it had long been the Crown Chakra of Santa Barbara eateries. Because Elias was a devotee of Meher Baba, the goddesses he hired to cook tended to serve up falafels with the abandonment of moths swooning toward the flame of fana, the glow of God intoxication. All that poetry and pragmatism blended together at noon. In a universe ontologically prior to granola bars, all of UCSB flocked to Baba’s like pilgrims to Mecca.

Since Elias left Isla Vista, decades ago, I have never eaten a falafel that came close. Nor have I visited an eatery with Baba’s vibe. Elias brought to Santa Barbara not only good honest food but spiritual vision. He taught us that whenever a beloved soul passes, as did his teacher, it is not the end of the relationship. It is simply that because we can no longer locate our friend in this realm, we discover it thriving in the uttermost regions of our own subjectivity: Soul to Soul.

You must be logged in to post a comment.