Santa Barbara’s Multilingual Messengers Bridge the Invisible Divide

Connecting with County’s Latino and Mixteco Communities During Coronavirus Crisis

By Delaney Smith | Published April 30, 2020

Thanks to our readers’ generous contributions to the SBCAN Journalism Fund, we

have been able to translate the following story into Spanish.

To learn more about the fund and make a tax-deductible donation, visit SBCAN.org/journalism_fund.

Haga clic aquí para leer este artículo en español

Long before the COVID-19 pandemic hit Santa Barbara County and triggered mandatory social-distancing orders, some residents have experienced a different form of social distancing for their entire lives.

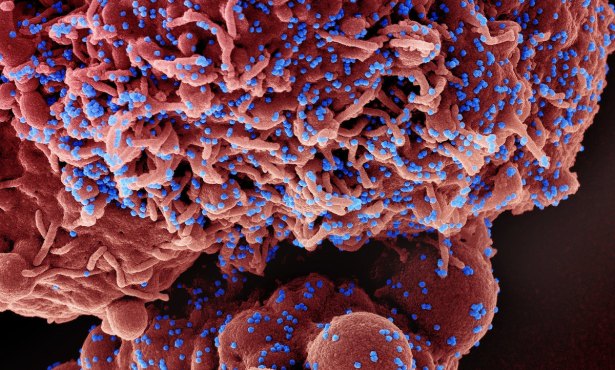

Pockets of densely populated communities throughout the county have historically been home to working-class, Latino families living near or below the poverty line. In Santa Barbara County, even though Latinos make up 48 percent of the population, 61 percent of coronavirus patients identify as Hispanic or Latino.

Across the United States, the virus has infected people of color at disproportionately higher rates than white people. The invisible separation between these individuals and their whiter, often wealthier counterparts has only been further highlighted by the stay-at-home and social-distancing orders imposed by California Governor Gavin Newsom.

“They don’t have the choice of staying home,” said Liliana Encinas, the City of Santa Barbara Fire Department’s bilingual outreach coordinator and the executive manager of Listos, the statewide disaster-readiness program for Spanish speakers.

“They try to take the precautions they can, but it’s really hard for that population,” Encinas said. “They can’t work from home…. They would rather go to work and expose themselves to the virus than not be able to feed their families. We’re in the same storm but not the same boats.”

People of color are more likely to live in poverty and lack adequate health care, which can lead to underlying health conditions. They often live in multigenerational housing and have to use public transit to commute to work.

Though an additional factor that could contribute to the disparity is language, it isn’t as simple as translating the English messages and delivering them through mass public service announcements. It has to take into account the invisible separation across cultural lines.

A Problem of Cultural Communication

“I personally don’t think language is the issue,” Encinas said. All the county websites posted information in both languages, she explained. “In all my years of disaster translating, I’ve never seen so much messaging go out simultaneously in Spanish.

“What I think is the missing link is cultural sensitivity and relevancy,” she continued. “The preliminary data showed Latinos were affected the most, but it also showed that only 20 percent of those who caught the virus don’t understand English. The problem isn’t as much language as the messages are not relatable to them.”

Supervisor Steve Lavagnino, whose 5th District encompasses Santa Maria, agreed with Encinas. He raised concerns early on in the pandemic that his Spanish-speaking constituents were not getting the message to social distance and follow the guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

“The reality is that Santa Maria can’t social distance,” Lavagnino said. “You can’t ‘Zoom’ to a strawberry field or a construction site. Then they come home to a more densely populated area than anywhere else. Multigenerational housing is the way that our culture is and the way people live here. It’s great for family bonding but not great for a pandemic.”

Many well-respected public officials with Hispanic backgrounds — including Congressmember Salud Carbajal, Santa Maria City Councilmember Gloria Soto, and retired judge Rogelio Flores — have posted bilingual warnings about COVID-19. However, Lavagnino believes that it is really one man who is succeeding in spreading the word about the dangers of the virus.

“Louis Meza did more than anyone in terms of reaching that community,” Lavagnino said.

A Man with a Message

Louis Meza is a 47-year-old father of two who’s worked as a chef and manager at the Hitching Post barbeque restaurant in Casmalia for more than 20 years. When the pandemic hit, he continued to go to work as usual and did not believe the virus was such a big deal.

“At the Hitching Post,” Meza said, “we greeted our customers, and we worked in tight quarters with people coming in from all over the place.… I never thought it was going to affect me.”

Then Meza came down with COVID-19 and was in the ICU. Though he was released after six days, his wife went to the hospital with COVID-19 symptoms and was put on a ventilator. Realizing that his wife, Melissa, was at death’s door, he took to social media to let his friends and family know about how deadly this virus really was. “By the time the hospital takes you in, you feel like you are on your deathbed,” he said.

“I think that did more than any elected official can do,” Lavagnino said about Meza’s social media campaign. “People can connect to someone in their community and see that this is not a joke; it’s real.”

Meza began to understand that his postings about his wife’s illness were reaching a larger and larger audience. He kept it up so others could see the devastating effects of not adhering to social-distancing orders. He said his first video is now at more than 74,000 views, and he’s been contacted by people all over the world who were moved by his story.

“I speak Spanish on my social media, too,” Meza said. “I felt like all the communication wasn’t getting out in the beginning, but it is now. A woman at the store yesterday recognized me and asked me how me and my wife are — and she was speaking in Spanish. She said she knows my story.”

His wife, 43-year-old Melissa Meza, has been hospitalized for almost a month. When her Marian Hospital doctor told Louis that she needed an ECMO machine, a highly specialized oxygenation machine that was only at Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, he was faced with a choice. The chances of Melissa surviving the ambulance ride were uncertain, but the ECMO treatment was the best that doctors could offer.

“The doctors said she might not make the ride to the new hospital,” he said. “Me and my family had to make that decision, and it was one of hardest decisions I’ve ever had to make in my life.”

But the move is proving to be successful.

“Melissa is awake now, but she still can’t talk,” Meza said. “Today the doctor let us FaceTime, and her eyes were fully open. I said, ‘I love you,’ and she mouthed, ‘I love you’ back, and we blew each other a kiss. My kids got to FaceTime her yesterday, and that was the first time they’ve seen their mom in 20 days. You could see the smile in her eyes.”

Translations and Translators

Alejandra Cortez, on the Santa Barbara Response Network’s (SBRN) Board of Directors, is one of several messengers in the county who realize that when translating a language, you must also translate the culture.

“They need to see someone who looks and talks like them so they know the person on the other end of the line won’t tell them ‘no’ or judge them if they need help,” said Cortez.

“To let the Latino community know about resources available to them, we started doing short interviews with Spanish speakers from community resources like the Foodbank, Stand Together to End Sexual Assault, and La Casa de la Raza,” Cortez said. “They [the Spanish-speaking community] don’t trust these brochures and websites.”

As social-distancing restrictions became tighter, Cortez had to move her interview setup to her backyard — but now the SBRN team also makes Spanish meditation and relaxation videos that are still geared toward Hispanic culture.

“We even have a video about feng shui,” she said. “You can do something small in your home wherever you are and make it feel nice.”

Traditional news media plays a major role in COVID-19 messaging, too. Radio Bronco 107.7 FM is one of the county’s most popular Latino media sources.

“In Santa Barbara, there is not a lot of Spanish media; it’s just us,” said Jose Fierros, the radio station’s program director. “It’s overwhelming how much info is out there. We just focus on COVID, COVID, COVID. It’s a big responsibility, but I feel very happy doing it for my people.”

He said that he oversees six radio stations, including Radio Bronco, covering South County in Santa Barbara, Goleta, and Carpinteria. Though his studio is in Santa Barbara, he has to broadcast from his home in Ventura to stay with his family during shelter-in-place restrictions.

“I’ve been doing two shows a day on Radio Bronco with Liliana Encinas,” Fierros said. “We talk about the news and recommendations for COVID. We invited elected officials, everyone, and we talk about what’s going on.”

Fierros also is on Twitter and Facebook every day, updating his followers in Spanish about daily case counts, new CDC guidelines, and more COVID-19-related information.

Radio Bronco isn’t the only non-Anglo media working to inform the county.

Arcenio López is the executive director of the Mixteco/Indígena Community Organizing Project, or MICOP. His organization is also the home of Radio Indígena 94.1 FM, a radio station with programming in indigenous languages, such as Mixtec.

The radio station is based in Oxnard, but López said there are apps available for Android and iOS devices to listen to the station in Santa Barbara County, as well as a way to listen via phone by dialing (605) 475-0090. The station aims to help the indigenous Mexican community overcome barriers of literacy, language, discrimination, poverty, and illness, as well as inform them in their language during times of crisis like the pandemic.

“It’s difficult to share some of the messages in Mixteco because there is no direct translation for some of the medical terminology about the virus,” López said. “Trying to describe what COVID is, we just call it a virus.”

López himself is very close to the issue, as he grew up in Oaxaca, Mexico, speaking Mixtec as his primary language and Spanish as his second. At 20 years old, he moved to Oxnard to work in the strawberry fields with no understanding of English. A year later, he worked on a vegetable-packing line while attending Oxnard Adult School to learn English and become a louder voice for his community.

“Historically, local government agencies have not done a good job at having diversity and linguistically sensitive people on their team,” López said. “In Santa Maria, there is a large indigenous population. Santa Maria government is very diverse, but they are still forgetting the Mixteca population.”

López is on the County Public Health Department’s Immigrant Health Rapid Response Task Force, a network of community groups that work to identify and respond to COVID-19-related concerns for Spanish-speaking and indigenous communities.

“We’ve been doing a lot more social media, but we usually have done direct outreach at laundromats or supermarkets before everything was canceled,” he said. “A good percentage of them cannot read or write, so we record our voices talking or videos for social media. We also do outreach through WhatsApp because it is the most popular.”

WhatsApp, a call and texting app popular worldwide, has become a vital tool for immigrants living in the United States to communicate with their families in their home countries because of the low cost compared to using the cellular phone network for calls and messages. Sending COVID messages out to Spanish- and Mixtec-speaking people through WhatsApp is a way to culturally tailor messages toward their preferred methods of communication.

Also in the Immigrant Health Rapid Response Task Force is Frank Rodriguez, from CAUSE (Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy). The Public Health Department relies on translators from its internal joint information center along with CAUSE for Spanish translation.

Rodriguez said creating culturally relevant videos that highlight crisis resources available to the community is vital. 805 UndocuFund, for example, is a disaster-relief fund for area immigrant families who aren’t eligible to receive unemployment or stimulus checks because of their immigration status. Both CAUSE and MICOP are partners in it.

Rodriguez’s videos are more like “intimate conversation” than straightforward public service announcements. CAUSE created a Spanish-language video about alternative ways to celebrate Easter, a holiday that holds cultural and religious significance for many Latinos.

Young, Unsung Translators

Santa Barbara City Councilmember Alejandra Gutierrez was raised on Santa Barbara’s Eastside, a predominantly Latino neighborhood, and has worked in the school district with Latino families for 20 years before being elected to the City Council last November. She said that some of the earlier messaging the city put out during the pandemic was not reaching Spanish-speaking families in her district.

“It is a cultural thing. Especially during the Easter season, it has been hard for people to understand why they can’t go to their tía’s house for Easter,” Gutierrez said. “Once it started to hit Mexico and the Mexican media started to show images of the virus in Mexico, a lot of the people here realized it was real, and they’re panicking.”

Gutierrez pointed out that although Spanish-language videos on social media are an effective way to reach people, not everyone has easy access to the internet. And if they do, unemployment forms, which can be accessed online, are translated via Google Translate and do not necessarily make sense to a native Spanish speaker, she said, let alone a Mixtec-speaking person. Because all physical offices are now closed due to the pandemic, she said, many in her community who know her call and ask for help.

“Yesterday I helped 12 people fill out unemployment forms alone,” Gutierrez said. “It started with four, and then the word got out. I’m really trying to encourage them to have their teenage child help walk them through. In a week, I easily go through it with 25 families.”

She said that ultimately, the first-generation children are the heroes in those families. Just last week, she said, she helped a mother over FaceTime with filling out an application. Gutierrez had forgotten how to say certain words in Spanish, but the woman’s 12-year-old bilingual daughter was able to bridge the gap between her mother and Gutierrez.

“That young girl doesnt understand the responsibility she has, but she is a key during this crisis,” she said. “They are little heroes in their own families.”

Gutierrez is passionate about representing her community and helping them to succeed.

“Overall, yes we need to work on [Spanish outreach],” Gutierrez said. “But also as a member of the Spanish-speaking community myself, we have to be proactive. We are learning. It’s not a time to point fingers or wait for someone to tell you what’s going on; we are all in this together.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.