La Artista Adriana Arriaga

Next-Generation Chicanx Art in Santa Barbara

By Charles Donelan | Published September 10, 2020

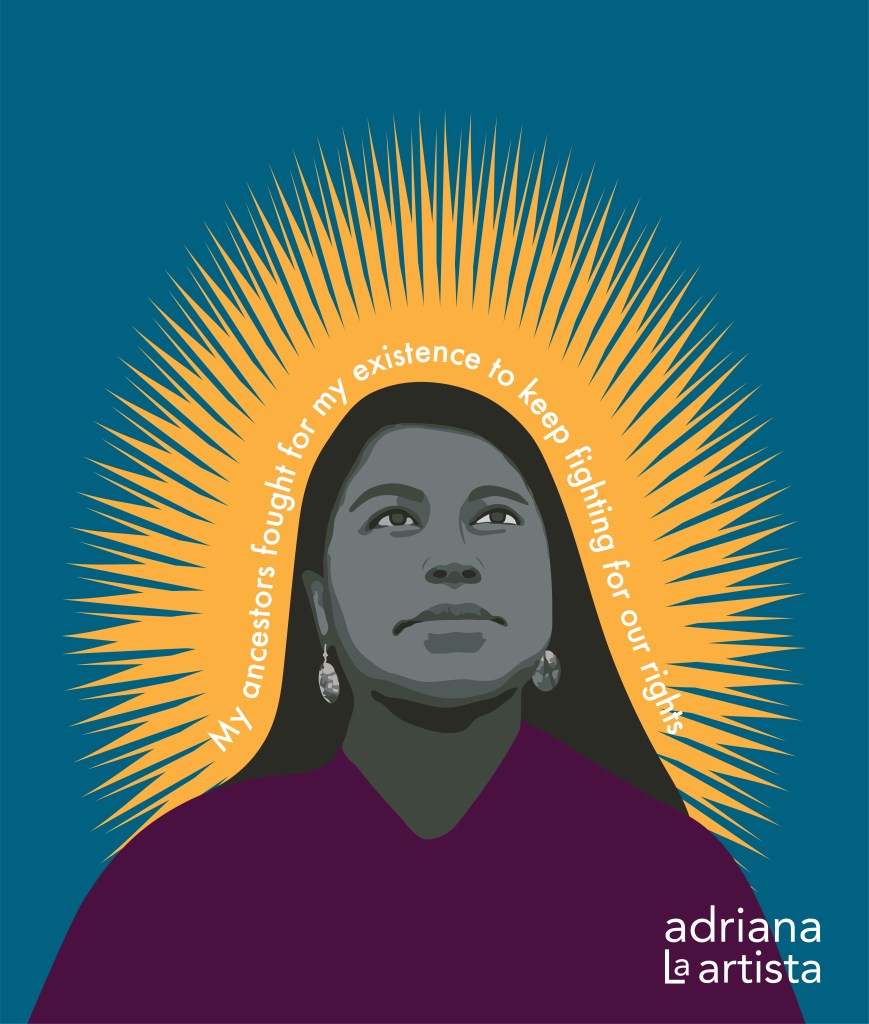

Not many people would have the nerve to step into the place of the mother of God, even if only for a picture. Yet for Adriana Arriaga, a Santa Barbara native and self-identified Chicanx artist, the impulse was something that she didn’t resist. “I was kind of tired,” she said in describing the inspiration for her self-portrait as the Holy Virgin, “and at the same time, I could feel myself as divine.” From these two currents in her body — exhaustion and an intimation of immortality — an image emerged. Monumental, haloed, and holding beads between her praying hands, the artist also appears naked and fierce. Her nails are blood red, there’s a gold chain around her neck, and big gold hoops dangle from her ears.

From a religious perspective, it’s provocative. Yet unlike many other ironic takes on the figure of La Virgen, there’s a warmth to the palette and a solid positivity in the composition that challenges facile readings of the image, which is titled “Pray for Me.” Arriaga is not the first, the second, or even the 100th contemporary artist to appropriate religious iconography, but there’s a distinct freshness in her approach to the gesture. Looking at her through the cultural filter of the icon, we are seeing something more than just youthful confidence. Through style, “Pray for Me” weaves a bright strand of nonchalant self-awareness into the sustaining fabric of Arriaga’s cultural heritage. While its title may only be one small word away from the expected “pray to me,” that difference marks a big distance. By traversing the emotional space between exhaustion and self-affirmation, “Pray for Me” retraces a path traveled by millions of people every day. It’s Arriaga’s knack for distilling such universal feelings into concentrated sets of visual elements that gives her work power. Like all of art history’s strong communicators, she makes great ideas pop.

Next Generation Networks

“Pray for Me” is currently part of a virtual exhibition curated by Michael Montenegro for Elsie’s, the old-school tavern on West De la Guerra Street. I didn’t meet Adriana Arriaga through the usual gallery scene. At the suggestion of my Indy colleague, Celina Garcia, I checked out her website, where I found a broad spectrum of creative projects, ranging all the way from a user interface she helped to design for the California Institute for Rural Studies’ Cal Ag Roots Project to a collection of witty and irreverent posters and stickers aimed squarely at youth.

Talking on the phone with Arriaga revealed the sharpness of the intellect behind this array of disarmingly direct images. Delving deeper into her work and her background revealed a story that not only touches on the ambitions of a new generation of artists of color but also highlights a statewide system of higher education that has, after decades of painstaking reforms, finally come into its own. For those who have wondered what the rise of ethnic studies within California’s vast network of public colleges and universities will accomplish, the long wait is over. Thanks to the multifaceted activities of a new generation of artists who are also social activists, the cultural tide in California is turning, and a feeling for cultural identity that’s flexible, imaginative, and more necessary now than ever is taking hold.

“Not Your Homegirl”

“I Exist”

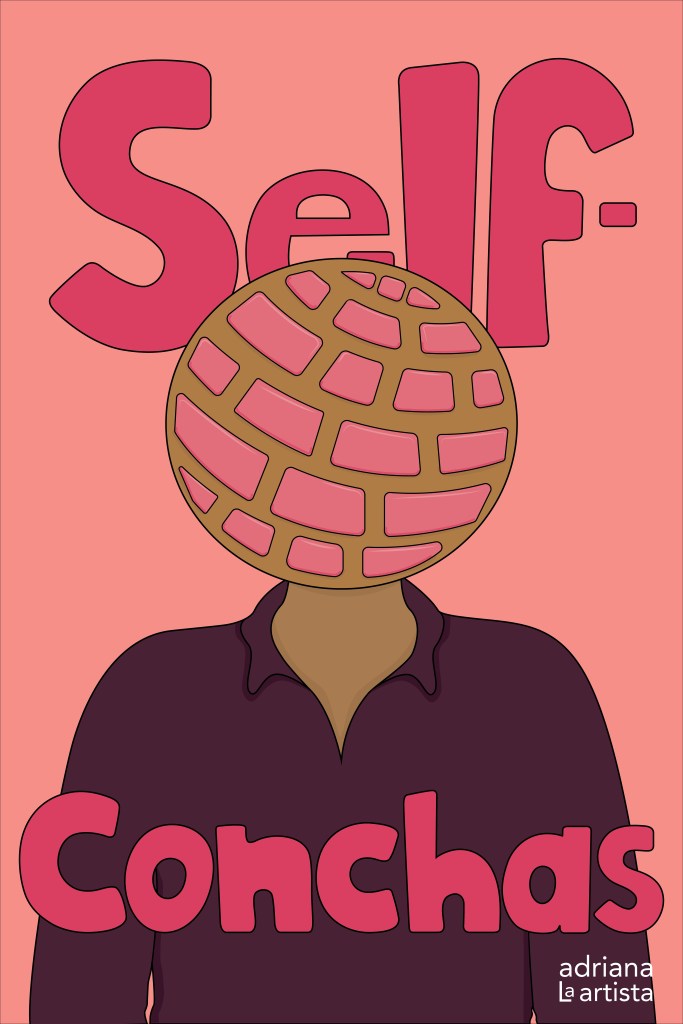

Self-Conchas

By the standards of our ever-more-precocious era, Arriaga came to her passion for art and graphic design relatively late. She didn’t start taking art classes until her senior year at Dos Pueblos High School, even though she had always enjoyed making things and dreamed of designing her own clothes. Prior to that, she had thought about being a lawyer when she grew up, but fate had other plans. Her next step up the educational ladder landed her at Santa Barbara City College, where she began to research her options for finishing her degree at one of the California State Universities. Although AB 1460, the bill requiring that every Cal State student take at least one three-unit course in ethnic studies before graduating, was only passed and signed into law in August, Chicano studies has been thriving on multiple Cal State campuses since the 1970s, and it was the program at San Jose State University that first brought Arriaga into contact with the network of mentors who precipitated her development into the public intellectual she is today.

Museum Takeover

The climax of Arriaga’s academic career came a little more than a year ago when she installed her master’s thesis exhibition at the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art at UC Davis. The Shrem Museum embodies everything that people expect from cutting-edge contemporary art spaces. The brand-new, green (of course), and distinctly postmodern building was designed by a team of architects whose collective experience includes city halls in Seattle and Newport Beach, headquarters for Adobe and Pixar, and, wait for it … the flagship Apple store on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. Even Arriaga’s UC Davis thesis adviser Tom Maiorana described the Manetti Shrem as “a really fancy museum.” And so it was into this socially sanctified space that, in spring of 2019, Arriaga brought Designing in Color: Graphic Design Through a Xicana Lens, which included multiple instances of her giant wheat-paste and paper posters and a mobile art distribution system labeled “Adriana La Artista” and modeled on street vendors’ food carts.

Memories of the working weeks leading up to the show remain vivid in Arriaga’s mind. “The last month I was just pushing through,” she told me. “I was very much alone. I would talk to my family back in Santa Barbara on the phone, but when you’re in school and you’re a first generation, you’re by yourself, you know?” She described the isolation of working in the studio late at night as both challenging and motivating, saying she knew the percentage of Latinos earning master’s degrees or higher is in the single digits, and she was keenly aware that, “I’m like that very small percentage that is happening,” adding, “the only thing that kept me going was how much I wanted to see my work come to life.”

The exhibition opening fulfilled Arriaga’s hopes and more. She remembers everything about the day with crystal clarity, from the outfit she wore to the sensation of seeing her work on the Manetti Shrem’s pristine white walls. Seeing the way people looked at her work touched something deep in her consciousness. She said that she loved how “these big panels of brown women were taking up that space.” “I’m thinking, ‘Dang, [that’s] my hard work,’” she said, but then qualified that sensation by saying, “That’s all the work I put in, but at the same time that’s my community up there too. They are the ones who inspired me.”

Professor Maiorana agreed, praising Arriaga for the way that she “uses illustration and graphic design in the service of community building.” “It’s so much more than the actual output,” he said. “There are these kind of intangible pieces that are just incredible.” Maiorana sees Arriaga as representative of where the UC Davis MFA design program is headed in this new century. I could hear the excitement in his voice as he described the way that “the program allows you to access things that you kind of already know,” offering Arriaga’s “La Artista” cart as an example of someone “unleashing the experiential knowledge that she had.” What this kind of work does, he said, is “help folks see themselves.”

Reading the Signs

When I asked Arriaga to expand on her interest in traditional Mexican-American iconography, she poured out waves of knowledge and speculation about La Virgen, La Llorona, and La Malinche, three distinctive feminine archetypes that have stimulated her thinking ever since she took a Chicana studies course with Professor Magdalena Barrera at San Jose State University (SJSU). Professor Barrera, who is now the vice provost for academic success at SJSU, honed her feminism-informed approach to the subject at the University of Chicago, where she majored in English and Latin American studies, and at Stanford, where she earned her PhD in modern thought and literature.

Professor Barrera has vivid memories of Arriaga’s participation in the SJSU’s Chicanx/Latinx Student Success Task Force, where she designed a logo and sticker that the school uses for branding the program’s new major. For Barrera, the key to coming up with truly resonant ethnic studies programs involves “moving higher education away from a deficit mentality.” “What strengths do they bring?” is the question more professors need to be asking. Assigning works that decenter the default culture allows students to connect their academic experience to their home identities. “It’s about an exchange,” said Barrera. She believes that Arriaga’s work represents the vanguard of what a student-centered curriculum can accomplish at the college level. “Her interest in design was accelerated by Chicana studies,” Barrera claimed, and Arriaga agreed, saying that at San Jose State she “started meeting Chicana feminist professors who were looking critically at our movement and calling out sexism and homophobia.” It was this perspective that catalyzed Arriaga’s ambition to combine graphic design with activism. “It was really important to me,” she said of this encounter, because it made her realize the significance of the shift from a Chicano to a Xicanx point of view. “The way I move is going to be very different from the way a Chicano artist is going to move,” she said.

Tom Maiorana praises Arriaga for “creating beauty out of things that are around.” Arriaga herself identifies at least some of what she’s doing as “rasquache,” a term that’s descended from the Uto-Aztecan language of the Nahuatl people of southern Mexico. In “rasquachismo,” the necessity of making do with recycled and upcycled materials is elevated from a sign of poverty to a blazon of ingenuity. Arriaga’s art cart exemplifies this technique, as it borrows the unpretentious appearance of the ubiquitous carts of street food vendors for the subversive mission of spreading messages of Xicanx resistance and solidarity through posters and stickers. Works such as the poster “self-conchas” and the sticker “not your home girl” exist to be read by those who can see in them a reflection of their own double consciousness, a structure of feeling that merges playfulness with defiance.

Talking with Arriaga about her emergence as an artist and an intellectual led us naturally to a discussion of family. “I remember when I started getting more into activism, my mother would be very upset,” she said. Her mom asked all the classic parental questions, like, “Where are you going?” and “What are you going to do there?” Looking back on these times, Arriaga said that she now sees that her mother was trying to protect her. “She was scared, right? Because she was like ‘What’s going on?’” The work that she did with Professor Barrera and others at San Jose State helped put this distancing from her home into perspective. “I can definitely say that I’m not the same person I was when I left school in Santa Barbara, and I’m really happy about that.” The reason? “I think that a lot of times people in power will tell us, ‘No, that’s bad,’ but when you get older, you have to say ‘no’ to them, and begin to resist, right? Because we have got to ask questions and look critically at what people are teaching us.” This ongoing project of balancing resistance with understanding radiates from every aspect of Arriaga’s growing body of work.

Let Me Reintroduce Myself

Since returning to Santa Barbara after graduating from UC Davis, Arriaga is grateful for having found a good job working for SEE International as a communications and design specialist. That’s given her some security as she navigates the community that she left in 2015. “I was gone, like, four years,” she said, “and I kind of felt like I had to reintroduce myself to the city. I was born here, but now I’ve got to get to know the streets all over again. Things are changing, and the people are different from when I left.”

The Women’s March and the June protests against racial violence helped, as they gave her settings in which to distribute her stickers and posters, which she gives away for free. As she sets about this highly self-aware project of personal reintroduction to her hometown, gratitude toward her academic mentors is never far from her mind. Of Tom Maiorana, she said simply, “He let me do what I needed to do.”

When I asked her what she hopes might happen next, her answer was equally simple, and just as strong: “I just want to make work, and I want other people to make work. I think Santa Barbara is one of those places where we can do that in showing who we are. It’s a ‘don’t forget who’s here’ type of situation, not just for my community, but for all the Black and brown communities in this place now. We’re here. For me, it’s about visual communication, but there’s much more to our stories than that.”

To learn more about Adriana Arriaga’s art, see adrianaarriaga.com and follow @adrianalaartista on Instagram, and to connect with a whole range of Chicano culture in Santa Barbara, follow @chicanocultureSB on Instagram.

You must be logged in to post a comment.