Inside the Organized Chaos of

Santa Maria’s COVID ICU

Marian Regional Medical Center Staff Never Seem to Sleep

Photos by Daniel Dreifuss | Text by Tyler Hayden | March 4, 2021

March 15 will mark one year to the day since the first case of COVID-19 was detected in Santa Barbara County. In that time, we have witnessed our region suffer and struggle but also bear down and carry on with incredible resilience.

We have not, however, been able to see firsthand the work of those truly in the trenches, the ICU doctors and nurses who day in and day out burn the candle at both ends to treat the sickest among us.

Until now.

For three hours in mid-February, Marian Regional Medical Center, an award-winning hospital located in the City of Santa Maria, where 10,777 cases have claimed the lives of 148 residents, granted Independent staff photographer Daniel Dreifuss unprecedented access to their COVID ICU wing.

Dreifuss shadowed staff as they pushed through another long shift of critical care. He captured their movements ― quick dashes down the hall, tender moments of silence with sedated patients ― and heard their thoughts of trepidation, determination, and hope. He watched as a man was intubated, a brutal but necessary procedure previously performed once or twice a month and now done multiple times every day.

This collection of images is a testament to the unrelenting pressures and continued fortitude of medical staff everywhere. They aren’t meant to shock but to reflect the true reality of what happens when COVID-19 brings a person to the brink of death. They are also a reminder that, despite the lifting of some restrictions, the virus continues to live and breathe in Santa Barbara County. Diligence remains the name of the game.

A few days after his visit to Marian, Dreifuss spoke about what he experienced and what he learned.

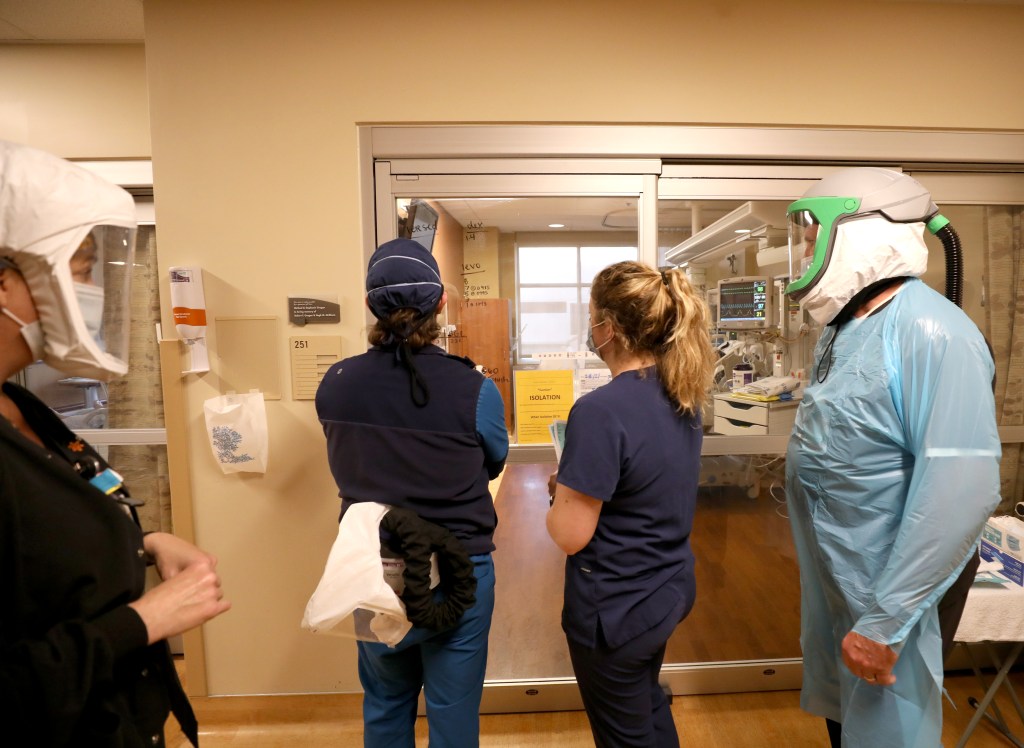

Staff spring to action as a case becomes critical.

A COVID-19 patient is hoisted onto a new bed to be intubated.

You visited the ICU just as the most recent surge was starting to let up. What was the energy like in there? How were the staff feeling?

There was still definitely a sense of urgency. I’m trying to find the right way to describe it… I would say there was hope but also discouragement at the same time, because the COVID patients kept coming and the staff were just exhausted. A nurse who’d been working there for 30 years said she never thought she’d see something like this. One doctor had to come in at 6 a.m. on his day off to help out. I was there for only a couple of hours and was tired by the end. They’ve been doing this for a year.

Dr. Zach Reagle performs an intubation.

Staff monitor the intubated patient.

What happened in those few hours? Were there spikes in activity, or was it more of a steady hum?

I would say it was more like a steady, high hum. One nurse described it perfectly as “organized chaos.”

Everybody has their job, and they do it really well to make sure the next person has exactly what they need to do their job ― from the nurse who preps patients for intubation, to the anesthesiologist who calculates how much of a sedation drug to give, to the respiratory therapists who consult with the doctors, to the doctor who checks the patients’ lungs, and so on. Not to mention the IT staff who make sure the machines are working right and the cleaning crews who prep and sterilize everything.

It’s definitely a team effort. It’s constant communication, and there’s always something happening. The pressure is unbelievable. Plus, every patient is different. This person might be diabetic; that one might have a heart problem. To be able to do that kind of work on a consistent basis at such a high level, well, I think it’s quite amazing.

A doctor, nurses, and a respiratory therapist discuss a patient outside their room.

Registered Nurse Bethany London straps on a protective mask.

Let’s back up a little bit. ICUs are highly restricted places, especially during COVID. How were you able to get access? Has Cottage or anyone else allowed you to document what’s actually happening inside their facilities?

No. Cottage won’t even let us on the property. They got mad when we tried to photograph a delivery of donated wine.

When I talked to Marian’s media person, I explained to her that the Independent thought it was really important to show what the doctors and nurses are doing and how they’re literally working around the clock. I said we wanted to help the public understand how serious this virus still is and how we’re not out of the woods yet. The New York Times wanted to use some of the images too. One actually recently appeared on their front page.

Marian had a few concerns about privacy and HIPAA, so we talked through them. They wanted to make sure I didn’t identify any patients. Of course I agreed to that.

Respiratory Therapist Jim Wahlig checks on a COVID-19 patient.

Registered Nurse Lois McKinley looks in on one of her patients.

Did you have any personal reservations about the assignment?

Yeah, because family members aren’t allowed in the ICU, and I was worried they’d be upset that a media photographer was given access over them. But I talked to a photographer friend of mine who spent several days in the ICU up in Salinas. One of the people he photographed passed away, and he posted the note that he got from the family, which thanked him for his coverage and said they were glad their loved one could help tell the story. That made me feel a little better.

Were you concerned about getting infected? Was your wife?

My wife was really supportive of the project, and she knows that I try to be safe when I go out and shoot. She also recognized the importance of going in there and documenting this.

I had on full PPE and didn’t actually enter patients’ rooms. They were sealed off. I also had a doctor with me the whole time to make sure I didn’t compromise my safety or anyone else’s.

I got tested a couple days later, which came back negative, and then again the next week. I’ve been trying to get tested every week.

An ICU nurse helps a COVID-19 patient FaceTime with an iPad.

Registered Nurse Bethany London updates patient information

You’ve been in war zones and other hairy situations. How did this experience compare?

It’s difficult in any situation to watch sick people or people dying. But this wasn’t like a war zone where I have to be diligent and check behind me all the time. And it wasn’t like a fire or natural disaster where I also have to be on my toes and constantly aware of my movements. In this situation, I concentrated a lot more on everybody else. I felt more focused on what they were doing instead of what I was doing.

There were some moments that were just really sad, though. One nurse said to me, “Last week, we had a day where five people died.” That was hard on everyone, she said. It made me stop and think about my grandparents and family members, and it was like, “This is a real thing. This can happen to anyone.” For instance, my sister got it and was very sick. She recovered, but she’s in the category of underlying conditions, so it could have gotten real bad real fast.

Did anything surprise you?

It was a little shocking to watch one of the nurses talk to the family of a sedated patient on an iPad. It was pretty surreal. Watching someone being intubated was intense, too. I’ve seen it on TV shows and stuff, but it’s a lot different in real life…. The doctors said they’ve gone from performing a couple of them a month to sometimes multiple a day.

Dr. Barry Feldman interacts with a patient.

A RN enters a room to assist on checking on a COVID-19 patient.

Were there any positive moments?

A doctor explained to me how they would look for small wins, like taking someone off a ventilator or seeing their status improve. They would remember those moments and try to keep moving forward.

One of the nurses, Lois McKinley, just had so much care, so much honor being there and treating patients. She’s the one in the picture holding the patient’s hand. That person was sedated on a ventilator. When she came out of the room, she turned the lights off and just stood outside and watched them for a minute before speaking with the doctor. I mean, she really cared about each individual patient. I don’t want to speak for her, but seeing some of her patients die ― that has to take a toll on her. But she’s doing everything she can.

Dr. Barry Feldman was the one who was there on his day off. He was really concerned about the recent spike. I felt like he knew everything about each patient and he seemed to have a good sense of everything that was going on. He stood out to me as someone who was just very passionate and very knowledgeable and doing everything he could to keep everyone alive, and hopefully recover.

Some of these images are hard to look at. Why is it so important for people to see them?

For one, I think there’s still a lot of people who still don’t take COVID seriously enough. There’s a lot of people who say, “Oh well, I might get minor symptoms, but I’ll be okay.” But I saw patients in the ICU who were normal and healthy before they went in and now they’re fighting for their lives on a ventilator.

I also think it’s important to recognize that it’s selfish to not take it seriously. “I don’t have to wear a mask, I can go party with people I don’t know, yada, yada.” There are repercussions. It’s not just about you. If you get sick, it affects these people who are working in these hospitals and are burned out. They’re working 12-hour shifts and then have to go home to their family or partner and put on a happy face and try to go to sleep. Day in and day out.

I honestly don’t feel like we give them enough credit. And I want people to see ― to really see ― what they go through.

At left, a respiratory therapist monitors his patient; at right, a registered nurse inserts a PICC line.

You must be logged in to post a comment.