Fresh Faces of Environmental Action for Earth Day

Introducing Eight Eco-Warriors from Santa Barbara County and Beyond

By Indy Staff | April 22, 2021

The founding of Earth Day in 1970 is inextricably tied to Santa Barbara, where a disastrous oil spill the year before fired up the nation’s environmental hackles and led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. Our region remains a hotbed for Mother Earth–minded preservation, planning, and restoration, carried forth by generations of eco-warriors, who’ve taken the form of every archetype — from activist to academic, lawmaker to litigator, farmer to philanthropist.

Today, many of the same battles persist over conserving landscapes, fighting development, cleaning up waterways, saving species, and bringing sustainability to everything. But thanks to the zeitgeist of Black Lives Matter and associated equity-aimed endeavors, the Earth Day movement also encapsulates environmental justice in 2021, an era where racial reckoning extends to all corners of society.

We’d like to introduce you to eight fresh faces of environmental action in Santa Barbara. Some of the following folks are new to town, some are multi-generation residents, and one is working on a more regional goal — but all are actively engaged in projects, policies, and programs that matter. We hope their stories inspire the next generation to follow in their footsteps.

Happy Earth Day. —Matt Kettmann

Jay Reti: Santa Cruz Island’s Science SupervisorLiz Carlisle: Sustainable Soils

Meredith Hendricks: The Deal Maker

Laurel Serieys: Urban Wildlife Expert

Teresa Romero: Protecting Traditional Resources

Summer Gray: Marine Justice Activist

Kristen Hislop: Watching Wind Energy

Christopher Ragland: Open Oceans for All

Jay Reti: Santa Cruz Island’s Science Supervisor

Jay Reti first visited Santa Cruz Island as a Paso Robles High student, taking a summer course in field biology on the largest of the Channel Islands. “That was my first exposure,” he explained. “I immediately fell in love with the islands.”

Today, he’s the director of the Santa Cruz Island Reserve, part of the University of California’s Natural Reserve System. With 41 properties totaling more than 750,000 acres of land, the NRS is the largest research reserve system in the world.

“We handle a majority of the research and education that happens on the island,” said Reti. “The goal I have for the research is to use the island to test conservation and land stewardship methodology, and export that to mainland California and globally. We’re really well poised to do that.”

While pursuing anthropology degrees at UCLA and Rutgers, where he got his PhD, Reti worked 15 field seasons in the deepest corners of East Africa, but he would visit the Channel Islands every time he came home. He lectured at UC Santa Cruz for a few years until seeing the Santa Cruz Island job posted in 2018, when longtime director Lyndal Laughrin, who’s been on the island for 55 years, decided to retire. If Laughrin’s tenure is any indication, the reserve director role could be a lifetime appointment for Reti, who is planning to move out there into a shipping container house with his wife and daughter in the future.

“I’m stepping into some tremendously big shoes, and I’m really humbled by it,” said Reti of Laughrin, who still lives on the island and helps with reserve projects in his retirement. “By our standards, the Santa Cruz Island Reserve is a remote field station. But compared to where I’ve worked, it’s not that bad. Plus, you don’t have to worry about spitting cobras and puff adders.” Despite that remoteness, the island is a “very heavily utilized reserve,” said Reti, who said 1,000 to 2,000 visitors clock an average 5,000 user days on an average year.

The “jack of all trades” job involves overseeing a small staff; keeping up relations with The Nature Conservancy, which owns the island, as well as the National Park Service and National Marine Sanctuary; processing research applications from scientists around the world; scheduling stays at the field station, where 40 people can sleep in normal times; and fundraising to pay for maintenance and more.

“We get everything from people studying subtidal zones to geologists to entomologists to people studying lichens and different kinds of fungi on the island,” said Reti, who noted that even art students use the island occasionally. “It’s extremely varied, and there is a lot of room for collaboration between all these disparate research groups, which makes it very exciting.”

Recent research of note is how the reduction in regular fog is affecting Bishop pines and endemic island scrub jays that have adapted to those trees, and a deeper analysis of the spotted skunk, which seems to be less prevalent than it was when island fox species were much lower. “The fox is the fastest to ever go from critically endangered species list to off the endangered species list in the world,” said Reti. “That’s fantastic, but what happens when it bounces back that quickly. Are they in direct competition with the skunk?”

COVID hit soon after Reti started on the job. “Over this last year, I’ve spent very little time on the island, but I’ve been completely swamped with work,” said Reti of his pandemic year. “I’ve been able to dive into some more nuanced aspects of the reserve that, if I was out there managing people, I wouldn’t get to do. There’s a silver lining for sure.”

He’s most proud of spearheading a regional climate monitoring project, which installed eight weather stations around the island to serve an open-access data system. “I would love in the future to see scientific publications that are citing these weather stations by people that don’t even have to visit the islands,” said Reti.

He hopes more people, especially Santa Barbara residents, will take the chance to see the islands for themselves.

“I would encourage everyone to visit the islands,” he said. “It’s very common to meet local people who have never been out here. You have this absolutely world-class, spectacular, stunning place an hour away.”

See santacruz.nrs.ucsb.edu. —Matt Kettmann

Liz Carlisle: Sustainable Soils

Liz Carlisle grew up in Missoula, Montana, listening to her grandmother’s memories about life in the Dust Bowl. “I was so compelled by her stories of an agrarian childhood, and I wanted that connection to the land,” explains Carlisle, an agroecologist and author who started teaching in UCSB’s Environmental Studies program in the fall of 2019. But those stories were ultimately tragic, as mismanagement of the land led to the destruction of countless communities.

After graduating from Harvard, Carlisle hit the road as a country singer and ran into similar reports. “There were a lot of farming families all over rural America who had incredible traditions of land stewardship, but were all constrained by essentially the same forces,” she explained, pointing to federal farming policies of the early 1970s that directed farmers toward chemical-dependent monocultures of commodity crops. “It not only encouraged but really forced farmers, as the Secretary of Agriculture said, to get big or get out.”

Motivations were multiple. The oversupply of food became a weapon of the Cold War, while corporations like Ford and Sears, which needed low-wage workers for their urban factories, influenced economic policies that encouraged rural flight.

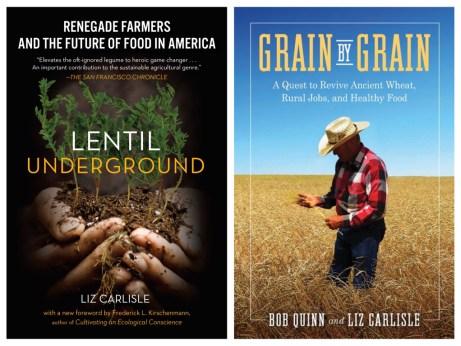

Carlisle found a savior of sorts in Senator Jon Tester, a flat-topped, missing-fingered Montanan who promoted organic farming and renewable energy over fossil fuels and extractive agriculture. After working in his D.C. office for a year, Carlisle went to grad school at UC Berkeley and then worked for four years at Stanford, along the way co-writing two books: Lentil Underground and Grain by Grain.

At UCSB, Carlisle is inspired by a focus on environmental justice and equity. “It’s just not acceptable to continue with the food system we have if you care about equity and climate change,” explained Carlisle. “The students I work with at UCSB understand that 100 percent.”

She’s about to publish her third book, Healing Grounds, whose working subtitle explains it all: How Farmers and Scientists of Color are Reviving Ancestral Traditions or Regenerative Agriculture to Combat Racism and Climate Change. “There’s beautiful symmetry to it,” she said of social and eco causes converging. “The land is the place where we need to find healing.”

The country may finally be prepared for such. “The experience of this global pandemic, as well as the racial reckoning of the BLM movement, has pulled back the veil for some folks on the structure of the food system that supports their everyday consumption of food,” said Carlisle. “I have seen people raise their voices.”

See lizcarlisle.com. —Matt Kettmann

Meredith Hendricks: The Deal Maker

Meredith Hendricks’s mother grew up on a Santa Barbara ranch. When she was young, she’d invite her pig Abigail into the house, they were such good friends. When she was a little older, she’d ride her horse through groves of walnuts, apricots, and berries down to the beach.

Within a generation, the century-old family ranch was gone, paved over by the Five Points Shopping Center. Hendricks, who grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area, traces a clear line between that loss and her ultimate career path of preserving natural landscapes and agricultural land. “It tugged at my heart,” she said.

After studying at UC Davis and protecting open space in Northern California, including as Director of Land Programs for the Save Mount Diablo land trust, Hendricks is now leading the Land Trust for Santa Barbara County. She started last fall, smack in the middle of the pandemic, but she hit the ground running ― the Land Trust is pushing ahead on a handful of major projects, including the finalization of one that will be announced in the coming weeks.

Hendricks, like the organization she now heads, is pragmatic about the complicated pursuit of land conservation. “There’s absolutely a place for development in the world,” she said. “People need a place to live and work and shop.” It’s mindless urban sprawl that she and trusts around the country push against, instead working with landowners willing to explore long-term options for preservation, including for habitat, recreation, or agriculture.

That effort often means “bringing odd bedfellows together,” as Hendricks puts it, from environmentalists to estate planners to ranchers to builders. But she enjoys it. “I like working with disparate entities to get on the same page and do remarkable things together,” she explained. And she’s well-suited to it, with a master’s degree in environmental business relations and true pride in her work.

After more than three decades of success in the southern parts of Santa Barbara County ― notching wins for Arroyo Hondo Preserve, the Carpinteria Bluffs, several Gaviota Coast ranches, and several other properties ― the Land Trust and Hendricks are now casting an eye farther north.

Trails and parks in and around Santa Maria and Lompoc “are getting loved to death,” she said, as sky-high housing prices push workers out of Santa Barbara. “As communities grow and get more complicated, it’s really important we match that with conservation and open space,” she explained. “We want to provide meaningful resources to everyone.”

See sblandtrust.org. —Tyler Hayden

Laurel Serieys: Urban Wildlife Expert

Laurel Serieys knew from a young age that she would need to get all the education she could in order to study and help animals, especially wild cats. As a high school student, Serieys read a scientific paper about “how most research, money, and effort is put into large cats, even though there’s 33 species of small cats that most people don’t invest in. So I was like, okay, maybe I should be a small cat person.” Serieys received her PhD in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology from UCLA, where she studied how anticoagulant rat pesticides affected the genetics and disease susceptibility of bobcats in Los Angeles. From there, she went to Cape Town, South Africa, as the project coordinator and founder of the Urban Caracal Project.

After six years in South Africa, her career studying smaller cats brought her back to the West Coast. On the Olympic Peninsula of Washington state, where Serieys is now, logging companies are collaborating with nonprofits like Panthera and with Native American communities to promote a more balanced ecosystem in which predators such as bobcats help control the mountain beaver population, which threatens young saplings.

Closer to Santa Barbara, Serieys is hopeful about the impact of the Liberty Canyon Wildlife Crossing, which is scheduled to break ground in 2021. “I think it’s a really amazing, excellent thing. And I know that a lot of thought has gone into it for many years,” said Serieys, who worked in that area between 2006 and 2014. “I was there when P-12 became the first cat documented as crossing the 101, and when that happened, I was also doing the genetic analysis for the mountain lion project. And we could immediately see his genetic contribution and how that really helped the population.”

Serieys believes that if the crossing can facilitate movement of more mountain lions in and out of the landscape, it will relieve multiple pressures on the cats, adding that another leading cause of mortality there is “mountain lions killing other mountain lions, presumably over fights for territory.” For eco-biologists and lovers of wild cats all over the world, Dr. Laurel Serieys is a source of information and inspiration.

See urbancaracal.org. —Paloma McKean

Teresa Romero: Protecting Traditional Resources

Teresa Romero’s career has taken her from nonprofit administration with the San Francisco Symphony to preserving treaty rights to hunt, fish, and gather for Michigan’s Little River Band of Ottawa Indians. “It was complex,” she said of enforcing an agreement from 1836. But now, she’s come home.

Romero runs the Environmental Office for the Santa Ynez Chumash, keeping a dozen grants and myriad programs on track, from monitoring the valley haze to nurturing native plants. “If you take care of the resources, they take care of you,” she said. “We have gathering permits out in the forest, and we’ve propagated 3,000 plants of 60 different native species.” Trial and error is teaching them which need a freeze or a burn to sprout.

“It’s about stewardship,” she explained. “When we care for our environment and our resources, our land and our waters, it protects our communities, protects our foods, our medicinal plants.”

This extends to trash. At the annual powwow, unlike most festivals, trash bins don’t overflow. Romero and her team start with the vendors, explaining the need to avoid single-use items — they’ve achieved a 90 percent landfill diversion rate. “There has been a huge focus on recyclables, but take plastic water bottles, for instance: Why put them in recycling when you can reuse them?” said Romero, who provides hydration stations for refills. “My hope is that when people observe what we’re doing, they think about what they’re doing at home.”

Romero is a member of the Coastal Band of Chumash and grew up in Montecito on the hill, canyon, and creek named for her family. She laughed as she said, “We all have a Jacques story,” referring to the infamous lifeguard who once patrolled the Miramar, running off the neighborhood kids who ventured too close to the resort. She left to study anthropology at Oregon State University.

“When you study anthropology and archaeology, you dig things up and study what’s been left behind. It really opens your eyes,” she said. “It becomes quite apparent that we’re leaving an awful lot of stuff behind. Where are those things going?”

See syceo.org. —Jean Yamamura

Summer Gray: Marine Justice Activist

Summer Gray stumbled into the world of environmental activism almost by accident, thanks to a friendly push from Mr. Nagler, a high school art teacher. Gray, the first in her family to attend college, grew up a blue-collar kid in the asphalt concrete wilds of Montclair, where San Bernardino County bleeds into Los Angeles. She was into art — the environment, not so much. Even so, Mr. Nagler recommended Gray for a collaborative arts and science fellowship in the Bahamas to study coral reefs. Witnessing the impacts of human development on the sea was a lightbulb moment for Gray, turning her on to the miraculous complexities of marine ecology and later to the more complex ecology of power, equity, and access as applied to the aquatic universe.

For the past four years, Gray’s been teaching environmental studies at UCSB. Along the way, Gray managed to be almost everywhere: monitoring climate-change negotiations in Poland, studying the impacts of sea-level rise in the Maldives, and co-authoring a scholarly treatise proclaiming the emergence of marine justice, a new variant in the realm of environmental justice.

Along the way, she also signed on with UCSB Professor Ed Keller to study what made some people more vulnerable than others to Montecito’s catastrophic debris flow in 2017 — essentially, why some got out and others didn’t. Her role was to interview 25 people who lived, worked, or did business in the upended area.

“I’m a qualitative researcher,” she said. “Data is effective, but what I’ve learned over time is that people resonate with stories.”

As an assistant professor, Gray has found storytelling a critical tool in teaching “community resilience.” Many environmental studies students, she said, find themselves overwhelmed by the imminent threat of the “slow incremental violence” posed by climate change. “I show little things that people are doing, like the Santa Barbara Soup Kitchen, for example,” she explained, “that give students a sense that they have a role to play, that show people can be involved in making change.”

See summermgray.com. —Nick Welsh

Kristen Hislop: Watching Wind Energy

Kristen Hislop grew up enjoying California to its fullest — the Stockton native and her family would often venture to the Sierra Nevada to camp amid its towering trees and imposing granite peaks and to the stunning beaches on the state’s coast. These experiences ignited Hislop’s love for environmental science, and she now manages an extensive portfolio of issues in her role as director of the Environmental Defense Center’s Marine Conservation Program.

Hislop, who holds a B.A. in geography from UCSB, was initially interested in pursuing a career in physical therapy, but she changed her path after becoming fascinated by undergraduate human geography and oceanography classes. She graduated from UCSB’s Bren School in 2010 with a Master of Environmental Science and Management degree.

Driven by a passion for protecting and preserving Santa Barbara’s abundant natural environment, Hislop works mainly on issues related to climate change, like fossil-fuel usage and the safe introduction of renewable energy sources. While renewable energy may sound like a straightforward way to mitigate climate change, inadequate planning could harm environments and communities.

“We want to make sure there are no lasting negative environmental impacts of renewable energy,” explained Hislop. “We take on that role not only as advocates of renewable energy but also in the venue of offshore wind, which is an exciting issue but should be coupled with protection.”

Hislop believes offshore wind is a viable energy source that must be thoughtfully implemented, and she is currently working with multiple state agencies to ensure proposed projects — including two near Point Conception — will be located in areas that reduce the risk to the environment and other user groups, such as fishermen and recreationalists.

“We have concerns about nearshore projects because many species are found in higher abundance close to shore,” said Hislop, who’d like to see them located further offshore and would like to “avoid unnecessary environmental and community impacts.”

“This is part of a bigger picture that we get to contribute to on a local scale,” she said of her work at the Environmental Defense Center. “Working in this field and this place is such a gift. It takes a long time to influence policy, but I’ve been in the field for enough time that I’ve seen some wins.”

See environmentaldefensecenter.org. —Lily Hopwood

Christopher Ragland: Open Oceans for All

Christopher Ragland credited his mother teaching him how to swim young and his early comfort with the beach as allowing him to become interested in pursuing environmental studies at UCSB.

Originally from San Pedro, Ragland said that he was fortunate to have this opportunity because many people of color don’t.

“I have Black family and friends now that don’t like going to the beach; they don’t like sand on their feet,” Ragland said. “They don’t like being in the water, and they’re not safe in the water. They don’t think that it is for them — it’s just not a Black thing to do.”

So after graduating UCSB and searching for his place in environmental work, Ragland eventually found the perfect fit when he combined his love for the ocean and water sports with his passion for environmentalism and social justice. He’s formed The Sea League — a year-round ocean sports league that is accessible to low-income youth of color and creates pathways to environmental stewardship. He wants to take it from a “fun first” approach rather than overloading the kids with facts.

The project began in January and is still small. Ragland has a team of five kids he takes surfing at Leadbetter Beach twice a week for two hours. He hopes to expand once he is able to get more adults involved to help take the kids into the ocean.

Rebuilding relationships between the natural world and communities of color is a central goal of The Sea League. All of the men older than Ragland in his family either are incarcerated or were previously incarcerated, and Ragland believes that he broke that cycle for himself because of his relationship with the ocean and the environment.

“It’s not like Black people never had a culture with the environment or the ocean,” he said. “It’s just that it’s sort of been erased and rewritten in a way where many folks don’t think they’re welcome.”

Follow his progress on Instagram at @_chrisragland. —Delaney Smith

You must be logged in to post a comment.