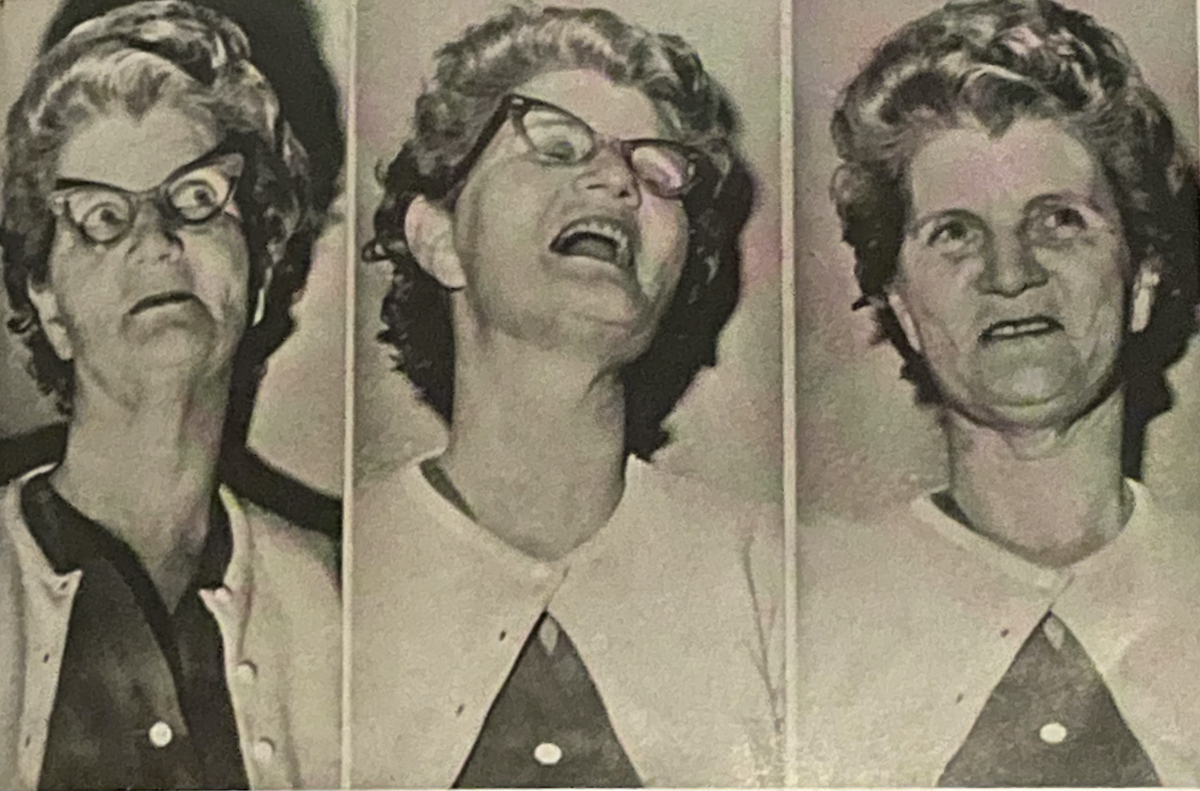

Elizabeth Duncan:

The Last Woman

Executed in California

New Book on the Santa Barbara Mother-in-Law Who Paid to Have Her Son’s Pregnant Wife Murdered

By Nick Welsh | October 13, 2022

Deborah Holt Larkin was an over-anxious 10-year-old living in Ventura in November 1958 when her father, a reporter for the Ventura County Star Free Press, began covering the story of a pregnant nurse in Santa Barbara named Olga Kupczyk, who had gone mysteriously missing in the middle of the night. Making it all the more ominous, Kupczyk’s purse and wallet were still in her Garden Street apartment, and her soon-to-be baby’s new clothes were folded neatly in plain sight. “It was a pivotal event in my life,” Larkin said during a recent interview.

Larkin and the rest of the world would soon discover that Kupczyk, a Canadian immigrant whose own parents had fled Ukraine during the violent aftermath of World War I, had been kidnapped, murdered, and buried — maybe alive, perhaps not — in a shallow grave near what was becoming the Casitas Reservoir just off Casitas Pass Road. She’d been done in by two brutally incompetent first-time hitmen hired by the insanely jealous Elizabeth Duncan, whose son, attorney Frank Duncan, Kupczyk had married just four months before.

Frank and Kupczyk met at St. Francis Hospital after his mother attempted suicide with an overdose of seconals. Kupczyk helped nurse Elizabeth Duncan back to health. Along the way, she and Frank — both just shy of 30 — connected, and romance sparked. But Kupczyk’s pregnancy and the ensuing marriage ignited the deadly fury that eventually sent Elizabeth Duncan to the gas chamber in the San Quentin penitentiary on August 8, 1962, as the last woman to be executed in California.

Following Duncan to the gas chamber later that same day were her accomplices, Luis Moya and Augustine Baldonado, two young men with histories of bad luck and even worse choices. Theirs would be the last triple execution in state history as well.

So much for morbid asterisks.

This story — imagine filmmaker David Lynch directing a lurid yet hilarious episode of I Love Lucy — has been told many times over since. It was a speedy trial by today’s standards — less than four years from murder to arraignment to trial to multiple appeals to execution. The trial took place in Ventura County, where the killing happened, though the killers and victim were all Santa Barbara residents. What Larkin brings to her book, A Lovely Girl, just released by Pegasus Press after nine years of work, is her uniquely personal connection to the case.

Larkin’s father, Bob Holt, began covering the Duncan murder case from the initial booking and arraignments of all three suspects in December 1958. He was there in San Quentin to witness as each of them took their last gasp of cyanide-laced air. The Duncan case was Holt’s biggest story, and he spoke about it often with his daughter, who was also utterly absorbed by the murder. Writing this book was, in part, a way for Larkin to honor her father many years after his death. They shared a love and connection that permeates the pages.

Larkin uses the Americana she and her family were living — pogo sticks, Formica, accordions, Ricky Nelson, Zorro, Sputnik, and the distant yet real specter of nuclear annihilation — the Ozzie and Harriet Golden Age of middle-class Southern California suburbia — as a foil to highlight the dark, twisted weirdness of Frank and Elizabeth Duncan’s world.

Even today, 60 years later, Larkin still can’t get over it.

Imagine a 54-year-old Elizabeth Duncan — real name Hazel Lucille Sinclaira Nigh — walking down State Street with her constant companion Emma Short, an 84-year-old former thrift-store owner and occasional grifter — to a dive bar and restaurant on the 400 block. They’re on their way to find someone to “take out” Duncan’s son’s pregnant wife. The owner of the club — Esperanza Esquivel — was willing to help because Frank Duncan was the lawyer defending her husband, Marciano Esquivel, on a stolen property charge. Esquivel connected Elizabeth Duncan with Moya and Baldonado. Both men had long criminal records, but nothing like murder. On November 13, they agreed to do the job for $6,000.

Four days later, they lured Olga Kupczyk Duncan, who had married Frank in June, from her second-story apartment to a car below, saying Frank was drunk and needed her help. The plan was to drive her to Mexico and make her disappear. Nothing went according to plan.

Kupczyk was strong and put up a serious fight. Moya and Baldonado pistol-whipped her so many times, the gun broke. The car, which they’d borrowed, had problems too; Mexico was out of the question. Pulling off to the side of the road on the way to Ojai, the two men took turns strangling Kupczyk. When they thought she was dead, they buried her.

It was never remotely a whodunit. Nurses who worked with Kupczyk told police how Elizabeth Duncan constantly threatened and harassed her. Kupczyk’s landlady remembered how Duncan would bang on Kupczyk’s door and pitch multiple fits. One such episode took place the night Frank and Kupczyk got married. That night, Frank went home with his mother. Most nights, in fact, Frank went home with his mother; he lived with his mother and visited his wife only occasionally.

The case broke wide open when a Santa Barbara detective named Charlie Thompson — so cocky and confident he used pens to do his crossword puzzles — thought to question Emma Short away from Duncan’s controlling presence. Short admitted that Duncan spoke frequently about how she wanted to kill Kupczyk.

Short was not the only one who heard about the mother-in-law’s murderous intentions. Duncan had asked a carhop at the Blue Onion Drive-In, Barbara Jean Reed, to splash acid in Kupczyk’s face, wrap her up in a blanket doused in chloroform, and then dump her body up in the mountains for $500. Later, in August, she asked a 26-year-old man whom she’d hired to impersonate Frank — for purposes of annulling the marriage under false pretenses — if he’d also kill Kupczyk. In September, Duncan asked Diane Romero — whose husband Frank Duncan represented on minor dope charges — but this time offered $1,500. There were others. Always, there was talk of acid, lye, chloroform, and pushing Kupczyk’s body off some mountaintop.

Nobody ever told Kupczyk. No one notified the police. Only Barbara Jean Reed approached Frank Duncan directly. “Your mother’s crazy,” she told him. But even Reed shied away from telling him what his mother actually said.

“Olga didn’t have to die,” Larkin concluded. “So many people knew.”

In December, Ventura authorities arrested Moya on charges of a parole violation, Baldonado for non-payment of child support, and Duncan for the sham annulment she’d attempted. On December 21, Baldonado cracked and led authorities to Olga’s body. On Christmas night, Moya confessed the crime to a street preacher. But Duncan would always insist on her innocence.

Larkin speculates that Duncan’s trial might never have stood up to today’s legal standards. District Attorney Roy Gustafson doubtlessly tainted the jury pool by making inflammatory statements — before jury selection — saying the crime demanded the death penalty. The trial took place before Miranda Rights had been constitutionally enshrined by the Supreme Court. Moya and Baldonado didn’t get attorneys until after they’d already confessed. Without Baldonado showing the way, the police may never have found Olga’s body.

Then there was the long and highly prejudicial digression Gustafson took exposing the fact that Elizabeth Duncan had been married 11 times, that she was a flim-flam artist and a grifter who wrote bad checks, that she worked in a house of ill repute to help put her son through law school, and that she lured men into marrying her by explaining that she needed to be married in order to inherit large sums of money. Later, when the men realized there was no inheritance, she’d try to shake them down for alimony. One of her many ex-husbands testified he’d been warned by a private detective that Duncan had hired him to throw acid in his face. It was all so shocking that the Duncan trial usually got top billing over other historic events during this period, such as when both Alaska and Hawai‘i became states.

It was all also highly prejudicial, utterly irrelevant to whether Duncan orchestrated her daughter-in-law’s murder, and strong grounds for a mistrial. Gustafson, the judge, and the defense team — made up of S. Ward Sullivan and Frank Duncan himself — all recognized how precarious this left the prosecution’s position. The judge’s solution? To instruct the jurors to simply disregard everything they’d just heard. Astonishingly, the defense acquiesced in the moment. Later, Duncan and Sullivan cited this wholesale character assassination in their fruitless efforts to appeal the verdict and the penalty.

Eventually, the case was appealed to Governor Pat Brown for clemency. By then, Brown, who was not supportive of the death penalty, had nevertheless weathered a firestorm of international disapproval for allowing the execution of Caryl Chessman, a man sentenced to death for raping women while pretending to be a police officer. When Duncan’s case came up two years later, Brown’s assistant charged with reviewing all commutation applications frankly acknowledged there’d been serious irregularities in the trial. But he also concluded that the evidence was so overwhelming that Duncan acted with malicious predatory intent, that the verdict would always be the same.

Larkin herself remembers, at the time, wanting Duncan to be executed. Her father, she said, had his mind changed by the experience. She recalled him telling her how the warden of San Quentin expressed doubt afterward that the people of California were any safer after Duncan, Moya, and Baldonado had been executed than they were before. “We do this on behalf of the people of California,” the warden said. “We don’t do it for us. The people of California should do what I just did.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.