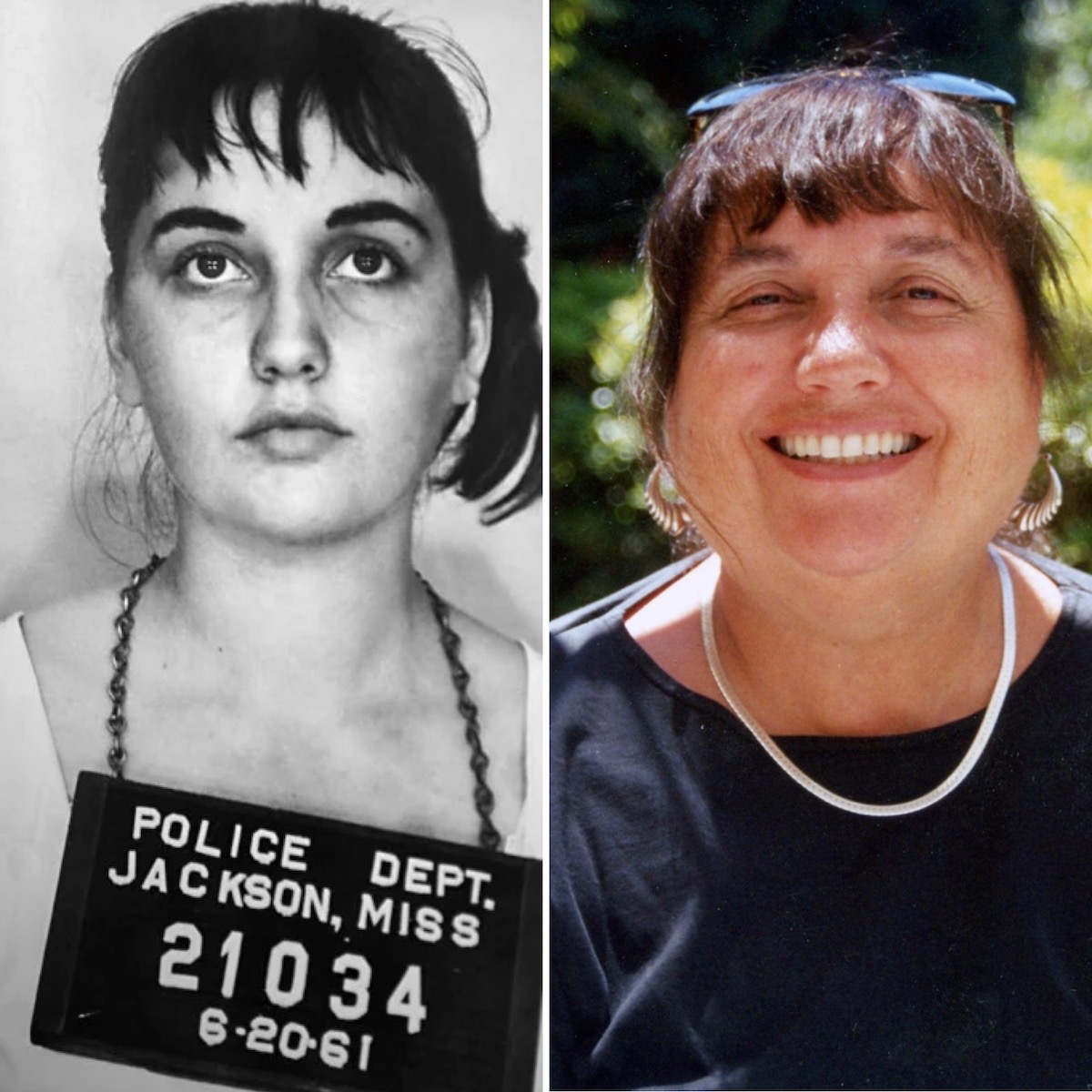

Jorgia Bordofsky died on September 28, “heading off to the happy hunting grounds,” as she liked to say. Never mind a little cultural appropriation; this turquoise-wearing Freedom Rider had earned a pass with a lifetime of bona fides.

The oldest of four children, Jorgia grew up in Los Angeles. Her father, Joseph Siegel, was a veteran of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade; her mother, Mollie Siegel, was a nurse and lifelong progressive activist. Jorgia attended UC Berkeley but left early to join the movement to desegregate the South. She was one of 450 Freedom Riders arrested during the summer of 1961 in Jackson, Mississippi, and completed a 40-day sentence at the notorious Parchman penitentiary.

In 1963, she married Allan Bordofsky, settling in New York, where she completed nursing school and had the first of four children. They moved to California, eventually settling in Santa Barbara in 1972 to escape the L.A. smog.

Jorgia was cheerful and kind, but also intense; she was often described as “a force of nature.” Nowhere was this more apparent than in her parenting. She was a dedicated stay-at-home mother who had high expectations and was not afraid to raise a voice (often), or even a wooden spoon (once). Children who misbehaved in the car would see their toys hurled out the window (the only time she littered) or be put out of the car themselves to walk home.

She insisted her family live in the top school district and that her kids have the best that school could offer. She taught other mothers that when the school secretary sees you coming, she should say to herself, “Oh shit, here she comes again.”

Respect and hard work were also expected. A child whose bed was unmade would be called home in the middle of the school day. And rather than receive an allowance, her children did yard work — gaining an understanding of the piece-work wage scale of immigrant Jews who toiled in garment factories at the beginning of the century — finding 10 dead snails for a penny.

Jorgia saw untapped potential in every young relative, neighbor, or passenger in her carpool, and she felt it her mission to cajole them toward studying harder, becoming a better person, and being more helpful to their parents. For the uninitiated, this might be off-putting. But for most, they grew a fondness for Jorgia, somehow understanding that this larger-than-life woman cared about them in a way that was unusual and special.

Jorgia’s Jewish identity was important to her, but she eschewed superstition and mysticism. Science, rationalism, and journalism would inform her, and common decency would guide her. She had a streak of contrarianism and was often ahead of her time. For more than 30 years, she worked as a Lamaze Childbirth Educator, preparing countless young couples for childbirth and helping them understand that childbirth is a natural process that should not be needlessly medicalized.

Allan died unexpectedly at the age of 59, and a shadow of grief would follow Jorgia for the rest of her days. To cope, she immersed herself in books, movies, lectures, and intellectual discussions with her many supportive friends. She was great company and a great talker. No one had more opinions, recommendations, or advice than Jorgia. At every encounter, she was ready with a book to share, a movie to recommend, or an article she had clipped. She was so sincere and enthusiastic that it was impossible not to forgive her being a know-it-all. In fact, she often did know it all — thanks to a near-perfect memory and a tremendous appetite to learn.

Jorgia enjoyed screening documentaries for Santa Barbara film festivals and Master Classes at the Music Academy. She was a docent at the Natural History Museum and was fascinated by Native American culture. She collected traditionally woven baskets, and turquoise jewelry was one of her few material indulgences. Traveling internationally was a special treat that she only got a small taste of — too expensive in her younger days, and too sad to do without Allan later on. Closer to home, she enjoyed winter trips to Yosemite and annual camping trips to Montaña de Oro, where she never tired of the coastal scenery and time with family and friends.

To many, Jorgia was their first friend in town. People were drawn to her honesty and authenticity. She was a particularly cherished mentor to her daughters-in-law. She set high expectations, but then set aside judgment and was unflinchingly supportive once decisions had been made. She nurtured individual relationships with each of her grandchildren and young relatives, generous in all things, except her compliments; these were usually spoken out of earshot, making her praise that much more meaningful when it got back around to you.

In living and in dying, Jorgia was fearless, resolute, and consistent. She talked about how death, like birth, is a natural process that should not be over-medicalized. In her last hours, she watched a UCTV feature on women scientists. She presided over a family dinner, and as she said her goodbyes and her thanks, she admonished us one final time to “do good things.”