Goleta History or Myth?

If the Shrapnel in

These Walls Could Talk

Are the Remnants of a

1942 Japanese Submarine Attack

Lodged in the Timbers Restaurant?

By Alex Scordelis | July 20, 2023

You never plan on getting tangled up in a mystery involving a Japanese submarine attack, a Goleta barbecue joint, a legendary Hollywood screenwriter, a golf-course cactus, and a UCSB physicist. But here we are.

I’ll start from the beginning.

Stumbling Onto a Story

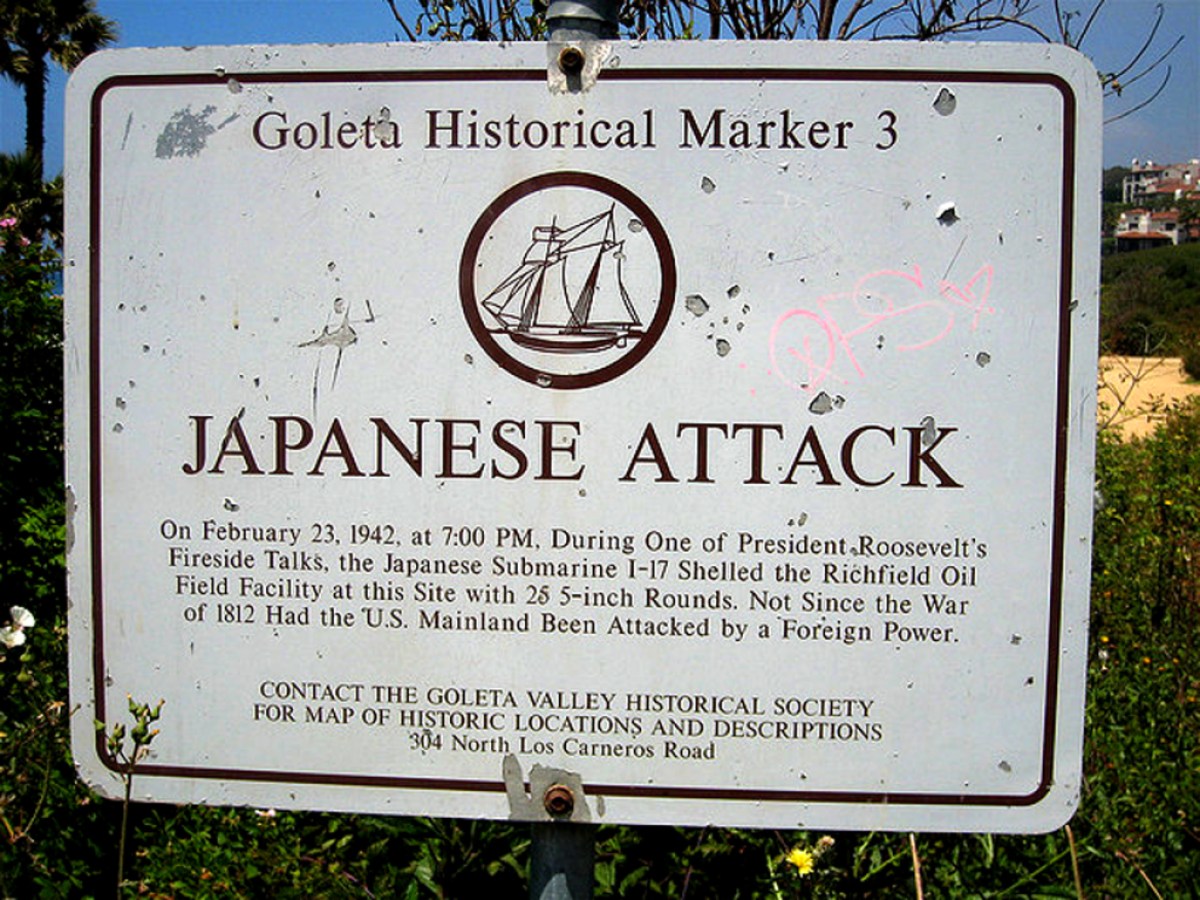

Several years ago, my wife traveled to Goleta for a work trip. We live in Los Angeles, and I courageously agreed to tag along for a two-night oceanside getaway. While she attended meetings one afternoon, I took a stroll along Haskell’s Beach. It’s a stretch of the coast I know well. As a student at UCSB, I’d often jog at Haskell’s to burn off calories acquired from a steady diet of Woodstock’s Pizza and foamy keg beer. On this particular walk, something caught my eye that I’d never seen before: a sign, partially obscured by a thicket of chaparral and coastal sage, that said “JAPANESE ATTACK” in bold capital letters. Alarming message aside, it looked like the kind of historical marker you’d see outside a New England inn, noting that George Washington once stopped there for clam chowder. Below the eye-grabbing headline was this:

On February 23, 1942, at 7 p.m., during one of President Roosevelt’s Fireside Chats, the Japanese Submarine I-17 shelled this Richfield Oil Field facility at this site with 25 5-inch rounds. Not since the War of 1812 had the U.S. mainland been attacked by a foreign power.

I was dumbstruck. The Santa Barbara coast had been attacked by the Japanese Imperial Army in 1942? In all the history courses I took in high school and college, no teacher had mentioned this. As a reporter for UCSB’s Daily Nexus (and as an Indy intern), I had immersed myself in the history and inner workings of Santa Barbara, but no word of this incident had ever crossed my desk.

I phoned my friend Brian, who lives near the site of the attack in Ellwood — the small section of Goleta just west of Costco, known for its monarch butterfly grove and 7-Eleven.

“How did you never learn about that?” Brian said, astonished at my ignorance. “Other than the War of 1812 and 9/11, it’s the only time the U.S. mainland has been attacked. You know the old Timbers restaurant off the 101? It’s built out of wood from a pier that was destroyed by that attack. It just reopened as a barbecue joint.” The 1942 incident caught my interest for being so strange, but throw a barbecue restaurant into the mix and you have my full, undivided attention.

As soon as I returned home, I searched for a book that might shed some light on the attack. The only one I could find was It Happened in Old Santa Barbara by Walker A. Tompkins. It was published by Santa Barbara National Bank, and bears no publication date.

I ordered a tattered copy on eBay, and when it arrived, I was surprised all over again. Tompkins writes that Kozo Nishino, the captain of the submarine that shelled Ellwood, was a well-known commander of a Japanese oil tanker before the war. In the 1930s, Tompkins writes, Nishino “suffered a humiliating loss of face” when, on a trip to the oil fields in Santa Barbara, he “stumbled into a patch of prickly-pear cactus.” That clump of cactus, Tompkins adds, is now where the 11th green sits at the Sandpiper Golf Club. When Nishino allegedly fell into the cactus, a group of American oil workers laughed at him. The indignity he suffered stung worse than the cactus, and he swore to get revenge. Hence, his stealthy but ineffective submarine attack.

The story was so silly, it jumped off the page: A humiliated sea captain pilots a submarine from Japan all the way to Goleta, does approximately $500 of damage, and injures no one before making the 5,388-mile trip home. And the only remnant of the attack is the Timbers, a restaurant off the freeway.

It seemed like a comedy I would want to write, but then I realized someone already had. In 1979, Steven Spielberg directed 1941, an ensemble action comedy starring John Belushi, John Candy, Mickey Rourke, and Dan Aykroyd. The movie begins with a Japanese submarine surfacing off the coast of Southern California. It seems to be directly inspired by the attack in Goleta — so I reached out to Bob Gale, co-writer of the screenplay, to learn more.

Burgers, Beer, and Back to the Future

I met Gale for hamburgers and beers on State Street, across from the art museum. In addition to 1941, which came out when he was still in his twenties, the part-time Santa Barbara resident co-wrote the Back to the Future trilogy with his creative partner Robert Zemeckis. Gale, 72, whose close-cropped hair matched his gray shawl-collared sweater, held court with a professorial air. As he sat down, he removed a black baseball cap that said “Doc Brown University,” a reference to the Back to the Future character. I asked if the hat was publicly available merchandise. He shook his head. “These hats were a gift to the cast of the Back to the Future musical in London.” Gale wrote the book for the stage show, which opened on Broadway this summer.

When I reached out to Gale and told him that I wanted to talk about 1941, he seemed amused. “It’s been a long time since I’ve had a request about 1941,” he said. Before it even arrived in theaters, Spielberg distanced himself from 1941, sensing that broad comedy might not be his forte. But a funny thing happened: The WWII farce found an audience of cable-watching latchkey kids in the 1980s. “Steven kind of disowned 1941 when it got lambasted by the critics,” Gale said. “But there are movies that a generation of kids grew up watching. Now they’re adults and they’re in charge of society, so to speak. And they love it — 1941 is one of those types of movies.”

I could’ve listened to Gale spin yarns about being on set with Belushi and Spielberg, not to mention his Back to the Future stories, but I was there with a purpose: I needed to know how and why he was inspired to turn the Japanese submarine attack on Goleta into big-screen fare.

“I learned about it, as it often happens, when I was researching something else,” he said. “And I don’t even remember what I was researching originally, but I came across this story about this false-alarm air raid in L.A. in 1942, now called the Battle of Los Angeles. And I said, ‘This is great material for a comedy.’ So I told Zemeckis about it. He totally agreed.”

Zemeckis and Gale took their idea to their friend John Milius, the screenwriter and director who, among many other cinematic achievements, co-wrote Apocalypse Now with Francis Ford Coppola.

“John had written [an unproduced] film biography of General Joseph Stilwell,” Gale said of the hard-

charging military honcho, nicknamed “Vinegar Joe,” who is played by Robert Stack in 1941.

“[Milius] knew that Stilwell had been stationed in California in the opening weeks of World War II. John said, ‘Well, we can move it to 1941 and then we can put Stilwell in it.’ So John kind of turned us loose and we started doing our homework. That’s when we learned that the event that precipitated the air raid was this submarine attack in Goleta.”

When I stumbled upon the historical marker on Haskell’s Beach, the story of the attack immediately struck me as comical, just as it did to Gale. I was curious about why he thought the submarine attack was funny.

“It wouldn’t be that funny if it had been more destructive,” Gale said. “But the thing about it, the reason that it rings true, is that if the submarine had aimed two degrees over, it could have done some real damage. And it’s hard to believe that they couldn’t have figured that out.”

While the attack on Goleta seems somewhat lost in the dustbin of history, Gale noted that the city of San Pedro hosts an annual re-creation of the air raid that took place over their city the day after the I-17 submarine shelled Ellwood. I asked him why he thought Santa Barbara had never hosted such an event. He shrugged and said, “Because it’s a footnote.”

As he picked up the check (I tried to pay, but he insisted), Gale revealed that, like me, he’s somewhat of a hamburger aficionado — that he and his wife seek out burger dives. I told him about the Timbers, the barbecue joint with Nishino’s shrapnel in the walls. He hadn’t heard of it.

“That’s cool,” he said. “Even if it’s not true, it ought to be true.”

A Mysterious Object in the Wood

The Timbers Roadhouse, built in 1952, reopened in October 2021, after a 15-year hiatus. As soon as I got there, I asked a server, a young, clean-cut man, about the attack and the shrapnel-studded beams. “You’re talking about the Japanese I-17 sub that attacked on February 23, 1942,” he replied. “Captained by Kozo Nishino. It unloaded 25 five-inch rounds. And yes, some of the shrapnel is still lodged in the walls of this restaurant.”

This server was like a human Trivial Pursuit card. I asked him if he was a student of history. “No,” he said. “I learned all that stuff on my first day on the job.” He took me into the dining room and pointed at an overhead beam. “You can see the shrapnel up there,” he said. I squinted and saw a sliver of metal.

I asked if he’d talk to me on the record. “I better go get my manager,” he said, and disappeared to a back room. He returned with Kim Stabile, co-owner of the Timbers.

Stabile, a native of Santa Barbara, had learned the story of the I-17’s attack as a child. She gave me a tour of the restaurant, which was packed for the Sunday-afternoon lunch rush, and handed me a menu. On the backside, just underneath the beer selection, was the history of how the wood from the destroyed pier was transformed into this restaurant.

The French dip sandwich I had at the Timbers was outstanding, but I needed a deeper understanding of the incident — more than the back of a menu had to offer.

Who Ya Gonna Call?

I asked around, and those in the know said that if one person could tell you all about the 1942 shelling of Ellwood, it’s historian Neal Graffy. On a day when this winter’s historic rain was coming down in buckets, Graffy met me in the back room of Harry’s Plaza Café. He walked in wearing a London Fog trench coat and a black cap, carrying folders filled with historical documents under his arm. He slid into the booth and fanned his folders across the table like a winning hand of poker.

“Most people don’t know about it,” Graffy said of the shelling at Ellwood. Last year, on the incident’s 80th anniversary, Graffy gave a talk about it. If you’re interested in the most accurate account of the shelling, that talk, available online, is the place to go. (Spoiler alert: He debunks the story about Nishino falling into the cactus.) I was fascinated to learn that Graffy has bigger plans for exploring exactly what happened that February night.

“What I have always wanted,” he said, “is to get the Navy to get me a submarine to come up out of the water at the exact time that the Japanese submarine came up, because I want to see what it would’ve looked like.”

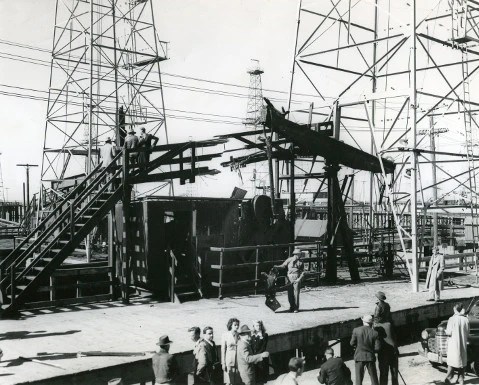

I asked Graffy about the Timbers legend that its walls contained shrapnel from the attack. He told me that in 1952, an entrepreneur named Tex Blankenship bought the land where the Timbers is now. To build the restaurant, he used wood from a dismantled pier — one that had allegedly been shelled by the Japanese sub. “Tex Blankenship was an incredible scrapper,” Graffy said. “He picked up all the lumber and built this huge restaurant out of it. I don’t know where the story first came from that the lumber contained shrapnel from the shelling.”

It’s a pretty amazing story, I said. Graffy shook his head. “When the restaurant was cleaned up about eight years ago, 10 years ago,” he said, “a guy went in there to steam-clean the entire interior, which was blackened from years of cigarette smoke. And there was absolutely nothing that they could find that looked like shells. And in talking to some of the old-timers that had built the Timbers, I said, ‘Did you ever see anything with shells?’ And they said, ‘Nah.’ ”

The Plot Thickens

Now I had a Columbo-worthy mystery on my hands: Is shrapnel from the 1942 attack actually lodged in the walls of the Timbers Roadhouse? Or is that just a tall tale? I went back to the Timbers for a closer inspection (and to eat more barbecue). As I tucked into a tri-tip sandwich, Kim Stabile came out to talk to me. I told her about this discrepancy. “I need to know,” I said, “Is there really shrapnel in the walls?”

“There’s some right there,” she said, pointing to a piece of metal in the wall about 10 feet away from us, below a TV playing SportsCenter. The metal was snugly wedged in the wood. It looked like shrapnel to my untrained eye. I went home and emailed Graffy.

“The pieces of shrapnel I’ve seen are large, not small slivers as I had imagined them to be,” he replied. “They were about two-and-a-half to three inches wide and about a half-inch to three-quarters of an inch thick. In the photos showing where shells hit the piers, the wood is torn up and splintered. I’m sure any damaged planking was replaced.”

[Click to enlarge] The commemorative sign at the Timbers Roadhouse (left) and ‘Attack on California’ exhibit at the Goleta Valley Historical Society in 2012. | Credit: Ingrid Bostrom, Courtesy

Graffy made a good point. Wouldn’t shrapnel destroy the wood, not go in cleanly? I needed to verify this, so I reached out to Ian Banta, a physics teaching associate at UCSB’s College of Creative Studies.

“There’s no reason why the shrapnel couldn’t have gotten lodged in the wood,” Banta said. “One can find many examples of bullets lodged in trees, and this would be similar. If the velocity is high enough, but the shrapnel is still small relative to the wood, then it would go through rather than destroying the wood. To destroy the wood itself, the shrapnel would either need to be comparable in size to the piece of wood or have something like an explosive that is triggered when it’s in the wood.”

The shrapnel in the walls appeared to be exactly the size Graffy said shrapnel should be. That, combined with Banta’s scientific explanation, leads to only one conclusion: That’s not any old metal in the walls of the Timbers. It’s shrapnel from a World War II attack on Goleta. The legend is real.

History Fades, but Stories Live On

In February, the last two oil piers at Haskell’s Beach were removed. They had stood there since the 1920s. Graffy was disappointed that there was no historical marker noting that those two remaining piers were shelled in 1942. Goleta Mayor Paula Perotte said in a statement, “This is a significant accomplishment. Indeed, old oil and gas infrastructure, piers, and wells are leaving our coastal waters for good.” She made no mention of the attack.

Like yellowed newsprint or Marty McFly in that photo from Back to the Future, history fades with time. But stories and artifacts of the submarine attack on Goleta haven’t vanished just yet. The Santa Barbara Maritime Museum has a section devoted to the incident tucked away on the second floor. And the Sandpiper Golf Club, where Captain Nishino allegedly fell into a patch of cactus, boasts a monument. I asked a clubhouse attendant if he knew where I could find it. “Of course,” he said. “It’s right out there.” He pointed to a large rock bearing a plaque just outside the pro shop. “It’s a popular item on scavenger hunts,” the attendant said.

I thought about the potential consequences of the attack. Did it lead to the concentration camps where Japanese Americans were relocated? I reached out to the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, and a curator said that the executive order opening the camps was signed on February 19, 1942 — four days before the I-17 submarine shelled the coast. There was no connection. In that regard, like Gale said, the attack is just a footnote. And yet it still captured his imagination, and mine, and maybe yours.

Over the years, some facts slowly erode and morph. But legends persevere and grow. It’s something to consider the next time you’re at the Timbers, enjoying a burger, and squinting as you look for slivers of metal in the walls.

You must be logged in to post a comment.