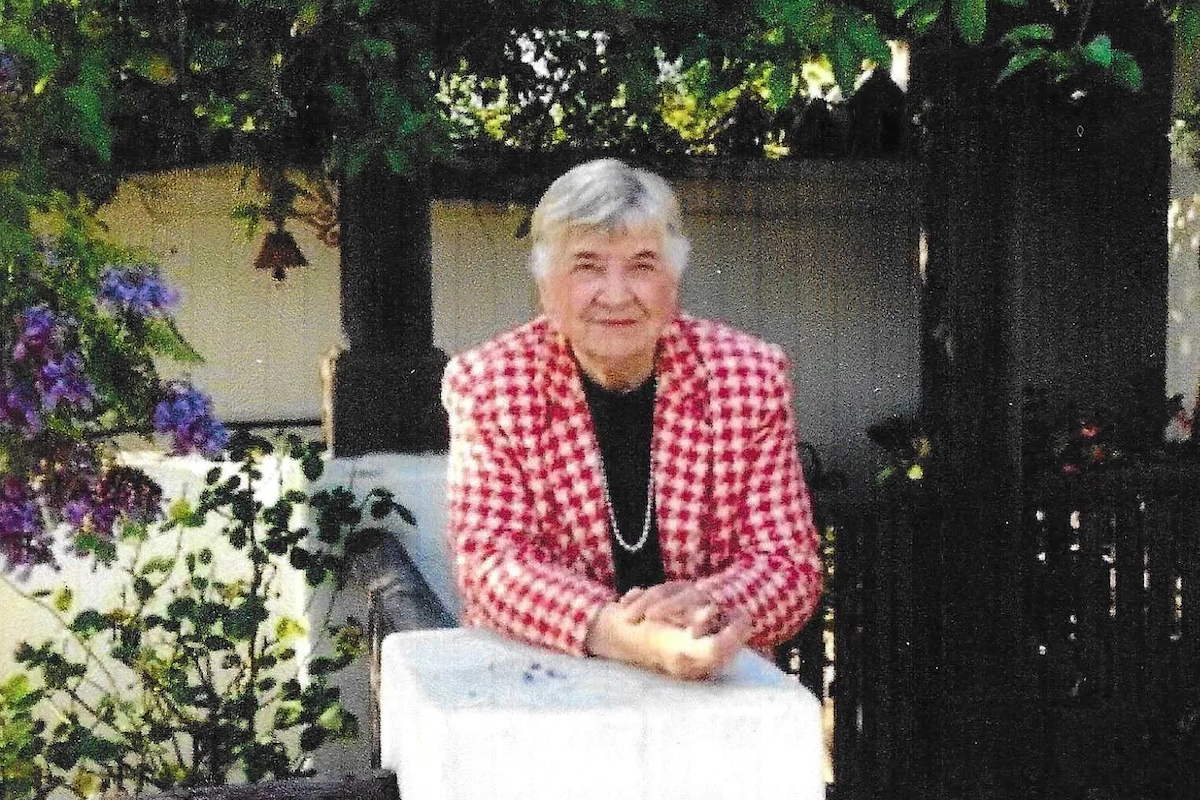

It’s hard to imagine the local news without Marilyn McMahon, the grande dame of Santa Barbara’s quixotic press corps. During 48 years at the News-Press, by her own estimate, she wrote more than 6,000 stories about her fellow Santa Barbarans, becoming a master interviewer and quintessential Woman About Town along the way.

Marilyn began her News-Press career in 1975 and filed her last story in late May. Then she fell and broke her ribs. Laid up in assisted living and then back at home, in hospice, with a lift to hoist her in and out of bed, she kept talking about getting back to work and finding someone to dictate stories to.

Marilyn’s former boss (and, unfortunately, mine), Santa Barbara News-Press owner and co-publisher Wendy McCaw, had shamelessly declared bankruptcy on July 21, and the historic institution where Marilyn had spent half a lifetime was dead. But, Marilyn told me on the phone one day, Bill MacFadyen, the founder and publisher of Noozhawk, the online news site, had offered her a job at age 93!

A little shocked by what Marilyn was telling me about her condition, I asked whether she would be confined to her bed.

“Melinda,” she retorted, “I can do a lot of damage in bed!”

That was Marilyn: an imposing woman with a hilarious streak and an unshakeable sense of who she was. She knew everybody, had a Rolodex crammed with 450 phone numbers and didn’t take no for an answer.

“She was endlessly curious about people,” said Kate McMahon, Marilyn’s daughter. “We used to call her The Interrogator. If you got with her, you were going to be held hostage to her questions. That’s what kept her excited about life, that she got to meet people and find out about their lives.”

Marilyn liked to throw the celebrities a little off-guard. She asked Hillary Clinton where she got her impressive green pants suit (it was from Talbots). She told Ken Burns, the documentary filmmaker, that he should ditch his bangs. (Burns demurred, saying he was still a Beatles fan.)

Marilyn was proud of a piece on the “Grande Dames of Santa Barbara” in which she featured Carol Burnett, the comedienne; Marilyn Horne, the opera singer, and Julia Child, the French Chef. But she was not happy when Julia asked Carol to do her Tarzan yell! Marilyn also said that Larry King, the television host, was the worst interviewee ever, replying only “Yes,” “No,” or “I don’t know” to her questions.

Jerry Roberts, who was hired as News-Press executive editor in 2002, recalled that on his arrival, “Marilyn barged in my office, helped herself to a seat, and proceeded to interrogate me. She apparently found me acceptable to her standards and spent months shepherding me to community events — La Recepción del Presidente, Channel City Club luncheons, a Visiting Nurse Association gala, for starters. She was my guide, and it was invaluable. How else would I have learned how the community worked?”

Providing much more than celebrity fare for what used to be called “the Ladies’ Pages,” Marilyn covered gardens, cooking, fashion, and the small things that bind a community together. She never complained about an assignment, even if it meant going to a vacuum repair shop. She could create something out of nothing. In one Sunday essay, recalling her Midwestern roots, she wrote poignantly about the meaning of a front porch as a place where people could talk to each other.

Marilyn was a graceful and conscientious writer, and her readers showered her with flowers, candy, and fan mail. She kept 48 years’ worth of her stories on newsprint in boxes in the garage. But she never said her job was easy.

“Feature writing is harder than the usual ‘who-what-when-where-how,’” Marilyn said during a Zoom presentation hosted by the Santa Barbara Yacht Club in 2020. “You have to figure out how you’re going to get the reader into the story, how you’re going to start.”

At her home with a big porch across from the Mission, Marilyn threw traditional parties — Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, New Year’s Eve, and Fiesta Pequeña during Old Spanish Days — inviting family and friends, including people who might otherwise have spent the holidays alone. For her 55th birthday party, not long before her divorce from Timothy McMahon, her husband of 28 years, Marilyn’s only guests were 15 of her favorite men, including her hairdresser and her dentist. Some arrived in tuxedos.

“Once you were in her circle, it was really hard to get out,” said Steve McMahon, Marilyn’s son. “You couldn’t do anything to alienate her, and I certainly tried. She just never let you get on her bad side.”

Marilyn was born Marilyn Kwiatkowski in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on June 8, 1930. She obtained a Bachelor of Science degree in secondary education from the University of Wisconsin in 1952 and taught high school English for 23 years, mostly in Santa Barbara.

Marilyn’s children recalled how their mother shot gophers on the front lawn from a second floor window at their house in Montecito; suffered through their father’s backpacking and rafting trips (she hated them); ran the Junior League of Santa Barbara; and rented out rooms to students after her divorce, drawing youthful energy from them.

“She was fiercely independent,” Steve said. “She was never going to be a housewife in the traditional sense of the word.”

Marilyn belonged to the women’s groups that merged with the all-male Channel City Club and University Club in 1988 and 1994, respectively. She also was the proud founder of the docent-led tours at the County Courthouse.

“She always made things work,” Kate said. “I don’t remember her ever being in fear or breaking down. She was like a tank.”

Marilyn loved teaching, but she loved journalism more. When she arrived at the News-Press at age 45, Tom Storke, a Pulitzer Prize winner, was the owner and publisher, and the pledge on the front page was to print the news “without fear or favor of friend or foe.” Marilyn was at the News-Press during the salad days of New York Times ownership from 1985 to 2000; and then the paper was unceremoniously sold to McCaw, a local billionaire.

In the summer of 2006, five top editors, including Roberts, resigned from the paper, alleging that McCaw was interfering in news gathering and reporting on behalf of her friends. Amid the meltdown, McMahon threw her support behind the newsroom effort to join the Teamsters and fight for a union contract. She was not afraid to represent the Teamsters at the negotiating table, though by then McCaw had fired 10 of us. Marilyn would roll into the room in a wheelchair.

“I don’t care if it’s the f—ing Mineworkers of America, we are going to have a union,” she said.

In violation of federal labor law, McCaw never negotiated in good faith. Dozens of reporters and editors quit or were fired under her punitive regime. But Marilyn stayed on, declaring herself to be the face of the resistance in what was left of the newsroom. After 2006, she never got a raise. When she died on August 24, she had outlasted the paper by five weeks.

“Marilyn was enormously proud of Santa Barbara,” Roberts said. “She had a deep knowledge of its history, a keen appreciation of its sensibilities and aesthetic, and embodied its values — civility, decency, integrity, compassion, and community service. She felt blessed to live in a special place and thought everyone else should, too. Gosh, what a great woman she was!”

Marilyn is survived by her son, Steve, of Carpinteria, her daughter, Kate, of Santa Barbara, four grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. Donations in Marilyn’s memory may be sent to Planned Parenthood or the Santa Barbara County Courthouse Docent Council.

The family is planning a celebration of Marilyn’s life at the University Club. Friends who would like to attend may respond to MkMcMahon23@gmail.com for upcoming details as to the time and date.

You must be logged in to post a comment.