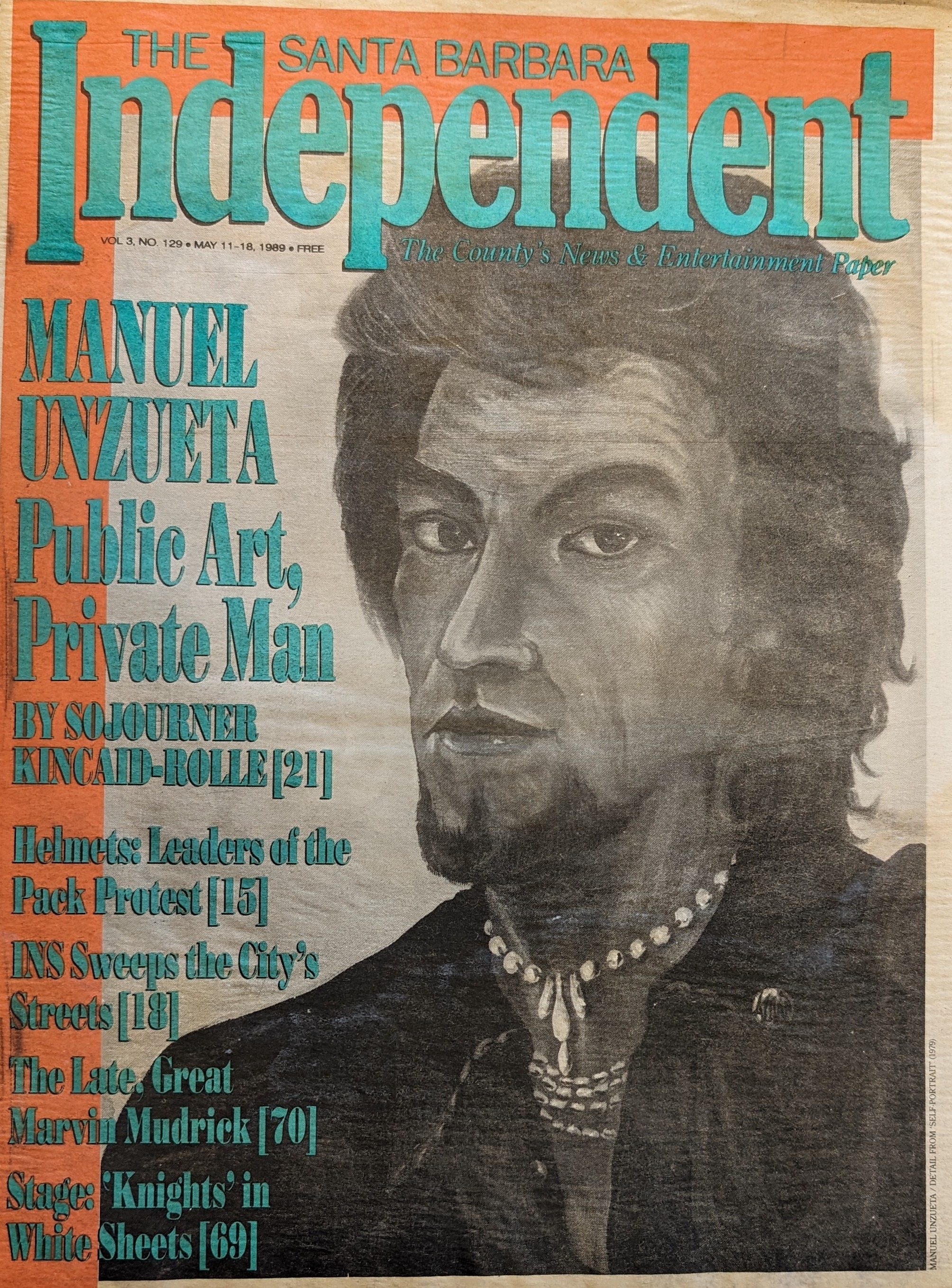

Manuel Unzueta’s Murals

Paint Stories on

Santa Barbara’s Walls

Portrait of an Artist as Activist and Educator

By Nick Welsh | Photos by Ingrid Bostrom

October 26, 2023

Maybe the single most revealing question any reporter can ask is, “Where are you from?” A close second is, “What brought you here?”

There’s always a story.

Most always, that story is much bigger — and much more interesting — than the person telling it thinks it is.

Aside from the Chumash — occupants of this chunk of land now for 12,000 years — none of us are original inhabitants. We all came from someplace else.

What drew us?

For most of his life, Manuel Unzueta — muralist, historian, Chicano activist, educator, soul-singer, soccer coach, story teller, and, yes, a Mexican immigrant — has been asking himself and the Santa Barbara community these very questions.

Why did we come here? And what did we find once we got here?

For nearly all this time, Unzueta has been painting his answers on giant walls throughout Santa Barbara County — maybe 50 in all. His work, it seems, is everywhere. La Casa de la Raza. All over Ortega Park. The Santa Barbara High School cafeteria. Santa Barbara Junior High School. Goleta’s Ellwood Elementary School. The Eastside Community Center and Franklin Library. The Westside’s Bohnett Park. The American Riviera Bank. The Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C., is exhibiting photos of Unzueta’s work, and he’s painted his murals in such far-flung locales as the state of Iowa.

No other public artist in Santa Barbara County is nearly as prolific or remotely as ubiquitous. Little wonder Manuel Unzueta has been enshrined in Santa Barbara High School’s Wall of Fame, perhaps the single highest honor Santa Barbara has to bestow.

With Manuel Unzueta, however, there’s never just one story. There are always many. At 74 years old, Unzueta seems almost giddy with life. In person, he’s enthusiastic, generous, smart, funny, proud, playful, patient, and precise. He tells his stories — even after all these years — with a mixture of astonishment and revelation. There are always digressions. One could easily suffer whiplash trying to follow along. But it’s well worth the effort to keep up.

On Thursday, October 26, Unzueta will stand in front of the massive seven-paneled mural he helped mastermind 45 years ago on Santa Barbara City College’s Campus Center, “Metamorphosis of Reality.”

He will be celebrating the new City College program Raíces — “Roots” in English — designed to support its first-year Latine students (pronounced “luh-teen-ay”) who are often unprepared for the cultural jolt of higher education. Latine students make up almost 40 percent of City College enrollment, but only 37 percent graduated last year. The Raíces program will provide more academic counseling, mentoring, and a safe haven for students, guiding them through this transition.

Speaking Art

Unzueta was selected as the keynote speaker at the event, according to Dr. Melissa Menendez, the City College English professor who helped secure the $3 million federal grant for the Raíces program, because, “His story is the story of so many of our students.” That Unzueta attended City College as a young immigrant from Juárez, Mexico, and later taught art and ethnic studies there for many years, adds to his unique qualification.

And perhaps even more compelling is the mural itself. Unzueta was the artistic force behind the creation of “Metamorphosis,” an 18-foot-high, 70-foot-wide cosmic, mythic, symbolically sumptuous mural. A controlled visual explosion of Chicano pride, it’s about struggle, oppression, resistance, and perseverance. Think 1970s Aztec warriors combined with Día de los Muertos calaveras. Most of all, the mural is an exaltation of education’s transformative potential.

The mural is for everyone. But it was intended to inspire those who got here the hard way, those for whom just staying here is the challenge.

The mural’s two left panels burst with images of war, death, and the Holocaust. On the far right, two panels depict the fruits of freedom, democracy, and education. In between, there are panels portraying the goodness of men and the power of women.

A smaller panel shows a woman’s hand pushing down, a man’s hand pushing up — two brown hands meeting at a yellow orb, red lines radiating outward. Unzueta explained that the orb represented a human egg and the lines represented sperm. “It’s the birth of a human people,” he said. “We wanted to make it a universal message.”

Unzueta’s murals never went in for visual small talk.

[Click to enlarge] On one side of “Metamorphosis of Reality” is murder and violence; on the other education and democracy. Unzueta’s murals never went in for small talk. | Credit: Ingrid Bostrom

Naturally, not everyone on campus was thrilled with the mural’s scale or content. “Some teachers were, ‘Can we do something more agreeable?’ ” Unzueta recalled. But if an artist wanted to show the benefits of democracy, he said, the perils of totalitarianism needed to be graphically depicted. And totalitarianism is never pretty.

The impetus for the mural sprung out of an arts trip to Mexico City in the summer of 1976. Unzueta — then a City College instructor — had taken 28 students to charge their creative batteries on the politically epic murals of legendary Mexican muralists Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco. Unzueta had first seen these works several years before and knew the powerful reverberations they could trigger. “It was just breathtaking,” he said.

He wasn’t wrong. When the students returned to campus, they wasted little time demanding space for a mural. And they weren’t asking. It was the 1970s; the Vietnam War was raging. The anti-war movement and the fight for civil rights, women’s rights, and environmental rights were in full flower. “They were highly politicized,” Unzueta recalled, “And they were highly aggressive.”

They got their wall, a big one, right outside the cafeteria. From fall through spring, they all worked every afternoon, weather permitting. Though many were artistically unskilled, they had lots of ideas. Unzueta translated their suggestions into visual images, while schooling them in the rudiments of mural-making. “I was not a yeller and a screamer,” he said, telling them instead not to panic and to just slow down. “I’d show them how to trace a big black line about one-quarter of an inch thick. And we got there.”

[Click to enlarge] Panels from Unzueta’s “Metamorphosis of Reality” | Credit: Ingrid Bostrom

It took about seven months. Even for a young man — Unzueta was then just 28 and still harboring dreams of becoming a professional soccer player — the work was physically grueling. “It was a killer,” Unzueta confessed. “A killer.”

Forty-five years later, “Metamorphosis” is still a powerful sight, but it has become fragile and the once-vibrant colors are fading away. “The sun hits the mural very hard every afternoon,” Unzueta explained. To restore it, he estimates, will take about four months of work. But organizers of the Raíces program are committed to making that happen.

Assuming Dr. Menendez and Raíces coordinator Sergio Lagunas can secure the necessary state funding, Unzueta will have to summon the strength to take on the task. After painting murals for nearly 60 years, Unzueta says his right shoulder causes so much pain he can’t even move his hand. The wall underneath the mural will need to be cleaned, the outlines retraced, and the colors repainted. “I will have to psych myself up, but we will redo it.”

In the Mexican tradition, he explained, murals are generally not intended to last forever. But when Unzueta and his students finished “Metamorphosis,” he clearly remembers thinking, “This mural was here to stay.”

History Ain’t Bunk

Listening to Manuel Unzueta tell his stories proves, yet again, that history is too interesting to be entrusted to historians. For him, history is a river forever rushing downstream.

Born in Ciudad Juárez on February 10, 1949, he is one of four children born to Concha and Manuel Unzueta, right across the Rio Grande River from the American city of El Paso. “I am a totally bicultural person,” he said in an interview on the podcast Ask Me Anything. “I was born with one foot in El Paso and one foot in Juárez with the Rio Grande running right through my heart and my mind.”

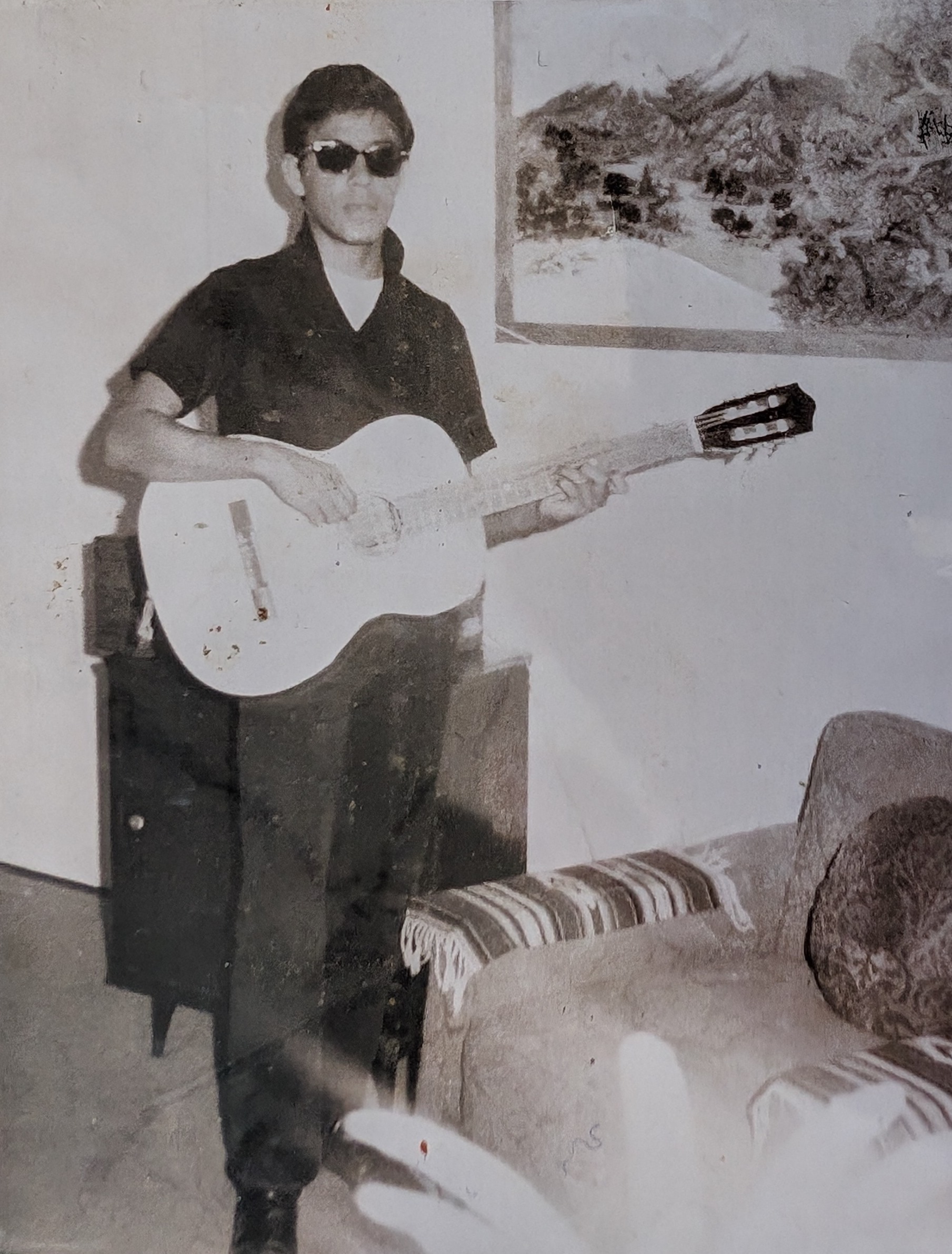

While undeniably poetic, this description is also factual. Unzueta grew up listening to the full panoply of Mexican music as well as sounds from across the river — the ever-outrageous Little Richard; the troubadour of El Paso gunslingers, Marty Robbins; and the King, Elvis Presley.

“I was a crazy kid from the barrio,” Unzueta said, always a little bit different. He collected bugs — cockroaches, spiders, scorpions — and even rats. And from an early age, he was always drawing. He loved drawing the bark of trees. He copied comic-book art by placing a pane of glass over the images and tracing them. He was further inspired by a street artist who had no hands or feet but had attached pencils to his elbows. To Unzueta, the drawings were amazing. At school, Unzueta was the kid whom other students asked for portraits and sketches. Pretty soon, his teachers were asking too.

But, like most of his friends, he was an avid soccer player. Unzueta recalls playing two games a day in 110-degree heat.

Unzueta says he was the only one of his friends who had both a mother and father, though his father would frequently work jobs in Santa Barbara, where the family had relatives.

His parents owned a barrio grocery store in Juárez where the whole family watched the news on a small black-and-white TV, and everyone kept abreast of current events by devouring three newspapers. The date November 22, 1963, is indelibly etched in Unzueta’s emotional memory. That’s the day President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. Everyone was crying, he recalled.

But a few months later, everyone was talking about a new band from England called the Beatles. Instantly smitten with “Love Me Do,” Unzueta started growing his hair long and soon formed a band with his buddies. When the Beatles appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964. his whole family watched. Listening to the girls in the audience screaming, Unzueta’s father asked, “Are they killing the girls, or what?”

About this time, Unzueta’s parents sent him off to St Joseph’s Catholic school across the border in El Paso to learn English. They were also worried he was running with a rough crowd. He was. Juárez was a rough city; gangs were rampant and teenage boys were expected to fight to defend their neighborhood. It was getting to be Unzueta’s time to put up or shut up. One night, when he and friends went out on the prowl, a robber grabbed him and held a knife to his neck. Unzueta was certain it was curtains. But he was saved by a car’s lights washing over him and his assailant. The would-be robber vanished. “Since then, I have never been afraid of anything,” he said

But his parents were.

In 1965, his father told him that he would be moving to the United States. No notice. No discussion. He would be going immediately in a car with his two cousins, José and Miguel, who had been visiting from Santa Barbara. Unzueta was 16 years old. He had three girlfriends. In his mind, he was on the brink of stardom as a musician and as a soccer player. “I had a chance to be somebody,” he said. He was crushed. His father was not moved, even though a neighbor warned them that Los Angeles — then in the throes of the Watts riots — was going up in flames. Unzueta remembers the drive north through the City of Angels. There was smoke everywhere. It was scary.

In Santa Barbara, Unzueta stayed on the Eastside with relatives from his mother’s side of the family. He knew some English, but not enough to be proficient. He was enrolled in Santa Barbara High, but it was mostly a miserable blur. He does remember tripping and falling in the hall only to see a beautiful blonde girl peering down at him. He spent the first six months hibernating in the garage. “I am nobody,” he remembered feeling.

It did get better.

The Santa Barbara Connection

Why Santa Barbara? Most immigrants from Unzueta’s home state of Chihuahua migrated to Texas. However, it turns out, Unzueta’s family has Santa Barbara roots dating back to 1870, making him both a first-generation immigrant and third-generation Santa Barbaran.

Many came here to work. One relative, his grandfather Pedro Quinteros, came to Santa Barbara in 1920. He was ordered back to Mexico shortly after the city suffered the devastating earthquake of 1925. Public sentiment then was that all jobs should go to native-born Santa Barbarans.

In Durango, Mexico, Quinteros met and married Unzueta’s grandmother Celsa, who had beautiful green eyes. They had four children, some of whom immigrated to Santa Barbara. One however, Conception, became Unzueta’s mother. Concha, as she was called, also had beautiful green eyes. She married Manuel Unzueta, who had worked the Bracero Program in the United States. Together, they opened their grocery store in Juárez.

That’s a convoluted yet incomplete account of how 16-year-old Manuel Unzueta came to have aunts in Santa Barbara. His oldest sister, Martha, had also moved to the city five years before Unzueta arrived, and it wasn’t long afterward that his parents and other sisters followed, settling into a home on Alphonse Street on the Eastside.

By 11th grade, Unzueta’s English improved, and he worked at Aaron Brothers restoring frames for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. His artistic chops got him a gig as staff cartoonist for the high school newspaper, The Forge, and his art teacher, Mrs. Strait, recognizing his talent, told him, “You’re too good for the regular assignments. Just do what you want.”

Unzueta enrolled at City College in 1968. When Santa Barbara was hammered by a massive oil spill in late 1969, Unzueta sketched the horrible scenes. Dead birds. Dead fish. His father, who was working construction, volunteered for the massive cleanup effort to save the birds and the beaches.

At the time, Unzueta played bass and sang for Kaptain Soul, a local band. He also had aspirations of playing soccer professionally. And his art was becoming much more politically focused. “I wasn’t a Mexican and I wasn’t a Mexican-American,” he explained. “I was a Chicano.” His art reflected that.

When Brown Pride activists congregated at UCSB to develop “El Plan de Santa Bárbara,” a 155-page manifesto of Chicano activism, Unzueta attended three workshops. Chicano activism, he said, was “to enroll people in the universities and colleges. That was it.”

Along the way, Unzueta also helped create La Casa de la Raza, a community hub for Latino activists, artists, and social service providers. He painted many celebrated murals there, photographs of which are now on display in the Smithsonian Institution.

In 1970, Unzueta got an arts scholarship to go to France and Spain; there, his mind was blown by the works of Francisco Goya, Diego Velázquez, and Pablo Picasso. When he returned, Unzueta knew exactly what he wanted to be: an artist. “And I already had a beret,” he said.

In 1971, he enrolled in UCSB, graduating with his MFA. His focus always was Chicano art. His professors were not encouraging. But Unzueta had already launched his career as a muralist. And while murals provided great exposure, they didn’t pay the bills. Over three years, he worked six jobs. He taught at City College. He coached soccer. He played guitar at weddings. He even released an album.

As a young man, Unzueta was drop-dead good-looking; as a public figure, he came across more serious than a heart attack. Mark Alvarado, a community activist and friend, studied with Unzueta. “When Manuel spoke, you weren’t listening to someone who’d just read 1,000 books,” he said. “You were listening to someone whose life embodied what he was talking about.” Alvarado believes Unzueta changed the trajectory of his life.

Unzueta is still plenty handsome, and more than plenty serious. But he’s not been immune to life’s vicissitudes. In the ’90s, Unzueta’s application for tenure at City College was rejected. During the Great Recession of 2008, Unzueta, his wife, and their two kids lost their Goleta home. In 2013, a fire broke out at Unzueta’s studio in his parents’ backyard. Before the fire was out, 200 paintings, 2,000 drawings, and a lifetime of photographs went up in smoke. About the only thing to survive was a rabbit whom Unzueta named Milagro, Spanish for “miracle.”

Today, Unzueta lives with his sister Martha in their parents’ home on East De la Guerra where the street fizzles out on its way up the hillside. His parents are gone now, but his two children — one an actor, the other a psychologist — often come to visit. In the backyard, Unzueta has created a lush paradise retreat with so many varieties of succulents that it’s a miniature Lotusland. Recently, however, Unzueta was drawn into the limelight again.

Back in the late ’70s, Unzueta had been at the forefront of an ambitious program to rehabilitate Ortega Park — then a serious public safety issue. Muralists were enlisted to paint a series of murals, and Unzueta was the best-known among them. Neighborhood kids were mentored. Over the years, maybe 50 murals were created. Of those, 18 remain.

Two years ago, the fate of those 18 stirred a contentious debate when City Hall announced it was pursuing a $14 million grant to redevelop the park. It did not mention the murals. A great hue and cry went up. The Historic Landmarks Commission and the Trust for Historic Preservation urged the city to consider saving some of the murals. Unzueta became a strong voice to protect the works.

He found himself bumping heads with younger, talented muralists — some of whom he had mentored earlier. They advocated for painting new murals rather than preserving older ones. Things got rocky. A compromise was reached. But the city lost the funding.

What happens next is unknown. An art consultant for the city has declared the Ortega Park murals of great artistic and historic value: “They explore histories unavailable in textbooks and ignite pride in the local culture that is often oppressed or undervalued, and are truly accessible to every member of the public who passes them by.”

Last Word

Making the strongest case for Unzueta’s legacy is Michael Montenegro, a Chicano cultural activist, historian, and podcaster. Next week, Montenegro will lead his ninth annual bicycle tour of the city’s murals, and Unzueta’s work will be one of the main attractions. “Santa Barbara would be a lot grayer place without him,” Montenegro said.

Montenegro — now in his thirties — took Unzueta’s class, where he learned aspects of Santa Barbara history he didn’t know existed. “That course changed my life,” he said. “And I mean that in a biblical sense. It removed the fish scales from my eyes.”

A recurring image in Unzueta’s murals, Montenegro noted, is the genie’s lamp. “The power of the genie lamp is fire. And in the 1970s, fire and education were joined at the hip. When you educate someone, you give them the fire. And that’s what Unzueta does. He shares the fire.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.