This article was underwritten in part by the Mickey Flacks Journalism Fund for Social Justice, a proud, innovative supporter of local news. To make a contribution go to sbcan.org/journalism_fund.

For about 13,000 years, Santa Barbara County’s rivers teemed with steelhead trout. They dwelled in its cool pools, journeyed to and from the ocean, and built spawning nests, or redds, in gravely bottoms. Until the 1950s, the area supported runs of tens of thousands of fish journeying upstream to spawn. Today, the Southern California steelhead is critically endangered.

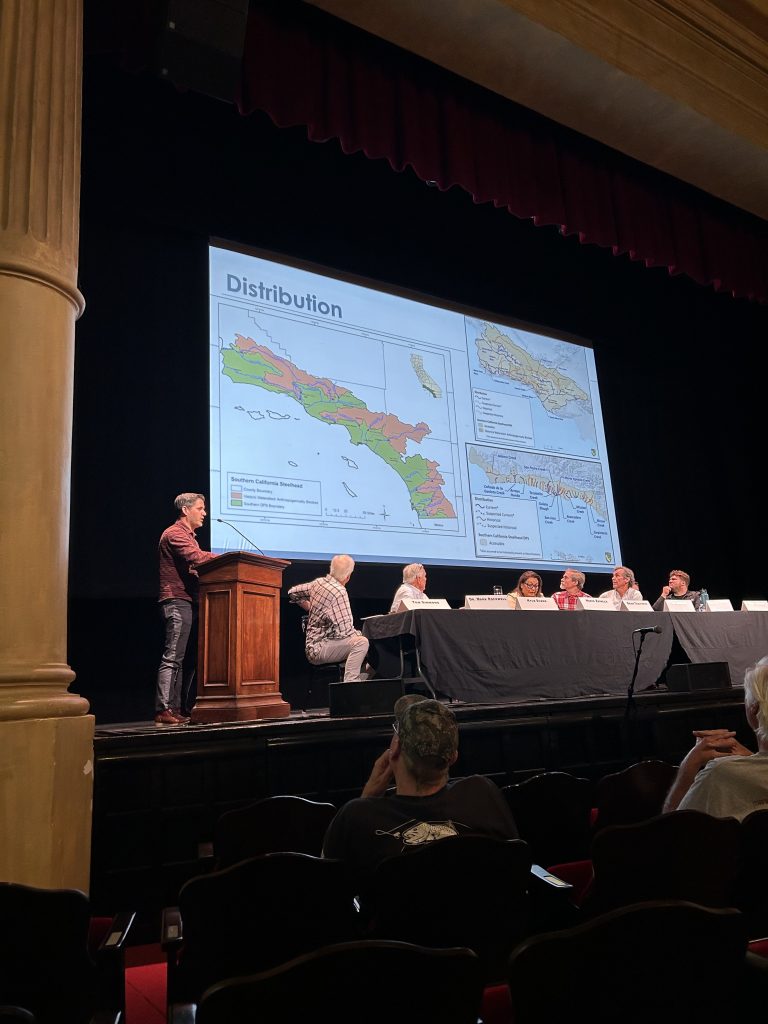

On Sunday, folks spent the afternoon at the Lobero Theatre learning about the southern steelhead. The event, part of the Santa Barbara Flyfisher’s campaign to “Save Santa Barbara Steelhead,” included a town hall with eight panelists who discussed everything from the historic and cultural significance of the fish to how to prevent its extinction.

“[The Steelhead] live in and enjoy the same things we like here in Santa Barbara,” said Mark Rockwell, the conservation committee chair for the Santa Barbara Flyfishers. “The ocean, the rivers, and the mountains that are behind us. They are all keys to their survival, and I think they’re keys to our enjoyment of this area.”

Tom Simmons, a conservationist and fly fisherman, moderated the panel.

Steelheads start their lives in freshwater, migrate to salt water, and return, swimming upstream to spawn. This journey differentiates them from freshwater rainbow trout. The two are the same species but the steelhead, with their ocean journey, grow larger.

“They need a lot of different habitat types,” said panelist Kyle Evans, who works for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife as an environmental program manager and who oversees fisheries in Southern California.

Evans said those habitats include spaces with spawning gravel, areas with fast river flow, deep pools, and riffles — shallow parts of rocky streams. One key factor? Unblocked, flowing water.

Evans showed a map at the town hall detailing where the fish had a high potential of existing historically, according to the National Marine Fisheries Service. The map showed almost every stream in the county.

But the ecosystem — and land use — has changed in the past 400 years.

Panelist Nakia Zavalla is the tribal historic preservation officer and cultural director for the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians. Zavalla said colonization in the area changed the landscape, along with impacting the people.

“It wasn’t just for our people, but it was for our surroundings. It was the plants, the water, that were all affected by these new animals that came to our land. And how it disrupted our ecosystem and how our people lived in harmony with it,” she said.

She said the steelhead was not only part of the diet for Chumash peoples, but also part of the cultural landscape. As the cultural director and travel historic preservation officer, she said, she looks at Chumash artifacts, including barbs people used to fish in fresh water.

Major obstacles to steelhead migration are river barriers, including dams. In the Santa Ynez River, which once attracted anglers to its abundant water, a series of dams was constructed starting in the 1920s.

The Bradbury Dam has a significant impact on steelhead in Santa Barbara. Completed in 1953, the dam diverted water from the newly created Lake Cachuma Reservoir for five water districts, four South Coast districts, and one in the Santa Ynez Valley, which resulted in increased urbanization in some areas. But it also blocked the fish from swimming upstream. Steelhead populations plummeted in the Santa Ynez River, from tens of thousands to below 100. Since 2011, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife has observed just ten fish in the river.

At the town hall, panelists described efforts to restore the steelhead population. Panelist Tim Robinson is the fisheries division manager and on the Cachuma Operation and Maintenance Board (COMB). Since 1993, COMB has monitored the fish. Today, Robinson said COMB surveys redds (nests), conducts snorkel surveys, and keeps track of invasive species and habitat quality. They are also working to remove barriers to the fish as they journey upstream to spawn.

“We’ve done 21 different projects out there to facilitate fish passage or improve habitats, and they range from the smallest of things, doing simplistic gravel augmentation for spawning, a $500 project, up to taking out a low-flow crossing and putting in a bridge, which is $1 million, $1.5 [million], sometimes $2 million for the project,” he said.

Other panelists detailed their own recovery efforts, as well as areas where attention is needed. Brian Trautwein of the Environmental Defense Center spoke about how regulating water wells would help prevent steelhead from dying due to lack of water. He showed an example from where a well had been turned on and killed dozens of fish overnight.

“Regulating water wells [in certain areas] would lessen this threat [to watersheds and wildlife], but currently [new] water wells don’t trigger any kind of environmental review [in several parts of Santa Barbara County],” he said.

Russell Marlow of the environmental nonprofit California Trout discussed recovery projects the organization is conducting around Southern California, as well as why they are needed.

“The threat of extinction is real — [in the] next 10 to 25 years. And so we need to be doing these projects yesterday, really, to see the impact we want to have and to ensure that this species exists,” he said.

Derek Koehler, the Koeheler winery manager, spoke about how private landowners could stay involved in barrier removal for the fish, and Nate Irwin of the Santa Barbara Channelkeepers discussed how healthy habitats for fish is part of a healthy watershed.

The Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians Cultural Director Zavalla said integrating Indigenous voices into the recovery effort is a means to bring both traditional and Western ecological knowledge toward a solution for recovery.

“This is great being on the panel with all these gentlemen here. But I want you to know these aren’t normal spaces we occupy,” Zavalla said. “This — a gathering of us together — really signifies a change. And I think it’s very important, bringing in tribes to have this discussion.”

Rockwell rounded out the event with information on how community members could help protect the fish, including organizing with the Santa Barbara Flyfishers.

Premier Events

Mon, Mar 09

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

ART 4 GRIEF Support Group

Sat, Mar 14

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Red, White, & Blues II: The American Songbook

Sun, Mar 15

3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Red, White, & Blues II: The American Songbook

Thu, Mar 12

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Poetry, Typewriters, and Collage Workshop

Thu, Mar 12

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening of Wild Hope: PBS Film Screenings

Thu, Mar 12

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Lights Up! Presents: “The Addams Family”

Fri, Mar 13

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

GLOW X: A High-Definition Neon Experience

Fri, Mar 13

7:00 PM

Goleta

Peace Event

Sat, Mar 14

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

The Vada Draw

Sat, Mar 14

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Lights Up! Presents: “The Addams Family”

Sat, Mar 28

All day

Santa Barbara

Coffee Culture Fest

Mon, Mar 09 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

ART 4 GRIEF Support Group

Sat, Mar 14 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Red, White, & Blues II: The American Songbook

Sun, Mar 15 3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Red, White, & Blues II: The American Songbook

Thu, Mar 12 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Poetry, Typewriters, and Collage Workshop

Thu, Mar 12 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening of Wild Hope: PBS Film Screenings

Thu, Mar 12 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Lights Up! Presents: “The Addams Family”

Fri, Mar 13 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

GLOW X: A High-Definition Neon Experience

Fri, Mar 13 7:00 PM

Goleta

Peace Event

Sat, Mar 14 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

The Vada Draw

Sat, Mar 14 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Lights Up! Presents: “The Addams Family”

Sat, Mar 28 All day

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.