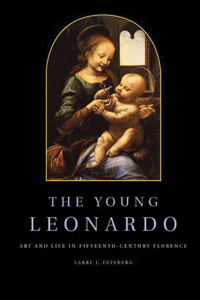

The Santa Barbara Museum of Art has flourished under Larry J. Feinberg, who came on board as director and CEO in 2008. As if that considerable task were not enough, Feinberg somehow managed to find time during these same years to compose a thoroughly satisfying and immensely readable account of the early career of one of the most important artists in history, Leonardo da Vinci. A scholarly work rather than a popular biography, The Young Leonardo: Art and Life in Fifteenth-Century Florence nevertheless remains unencumbered by the torturous theoretical prose or heavy-handed political agendas that too often limit the appeal of such undertakings.

Deploying his wide-ranging knowledge of the period and of Leonardo’s oeuvre in 28 relatively short and lively chapters, Feinberg takes his readers on a fascinating tour of what is known about Leonardo and his art, from his earliest days until his residence in Milan at the court of the sinister Ludovico il Moro Sforza in 1482. Feinberg moves easily between accurate, telling commentary on specific works like the “Madonna of the Carnation” of 1476-78 and the “Benois Madonna” of 1478-80 and the many, many pages of sketches that Leonardo created of an almost bewildering array of scenes, figures, and mechanisms. We may know his angels and waterwheels, but how many of us have seen, never mind understood, Leonardo’s imaginative renderings of an early snorkel for saving drowning sailors, his homoerotic images of John the Baptist, or even a scandalous illustration of Aristotle receiving a whipping from his notoriously dominant partner Phyllis.

While the book succeeds in demonstrating the range of Leonardo’s interests, Feinberg is circumspect when it comes to propagating the myth of the artist as the original “Renaissance man.” What characterizes Leonardo’s genius for Feinberg is not so much the absoluteness of his understanding as his intellectual restlessness, the continual need he appears to have felt to keep moving from one problem to the next. One aspect of the man’s career, in which difficult problems were never in short supply, was the artist’s relations with his patrons and colleagues, and on this topic Feinberg’s meticulous scholarship shines. Assassinations, executions, and political coups all have their place in this narrative, and their consequences, such as the swinging corpses of those hung in connection with the so-called Pazzi plot against the Medici, even find their way into the artist’s drawings.

Ultimately, what one takes away from the experience of this profoundly satisfying book is a double sense of accomplishment. First, of course, is the nearly incredible productivity and intellect of da Vinci, a man who mastered more than most would ever imagine essaying. But a close second is the sense of satisfaction gained from prolonged exposure to the best of what has been thought and done in human culture, something that Feinberg has clearly undertaken in a sincere and wholehearted manner. The fruits of his authority, and of his firsthand acquaintance with so many relevant pieces from collections all over the world, hang together in a single tapestry that adds enormously to our appreciation of such great works of art as “The Last Supper,” and we should be grateful to count the author as a member of our community.

SPLENDOR OF CUBA: Another Santa Barbara resident has graced our desk with an extremely gift-able coffee-table book just in time for the holidays. Photographer Brent Winebrenner has collaborated with author Michael Connors on a volume for the venerable house of Rizzoli called The Splendor of Cuba: 450 Years of Architecture and Interiors. Connors’s text contains lots of intriguing information, but the star of the show has to be Winebrenner’s lavish color photos; some wonderful prints from the book are on view at Samy’s Camera (614 Chapala St.) through Tuesday, December 20. n