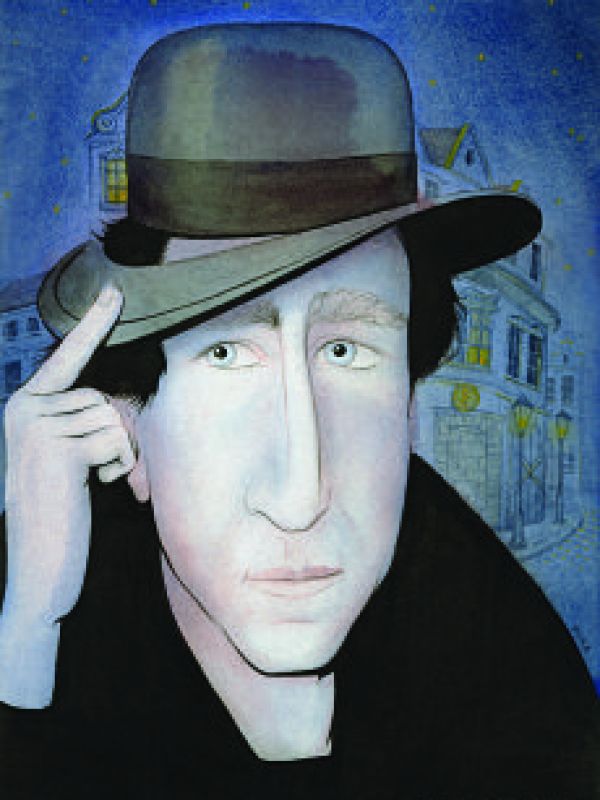

Ernest Sturm

Ernest Sturm passed away in the French Alps town of Montaimont in the early morning of October 28, 2016 with his wife Fuka at his side. Born in Vienna, Ernest’s family escaped the Nazis by first moving to Bogota, Colombia, and then settling in New York City. Ernest was a graduate of Brown University (1955) and NYU Law School (1959), and practiced law in New York City and Washington, D.C. for a number of years. He then turned his attention to French literature and earned a PhD in Romance Languages from Columbia University in 1967. He joined the UCSB French Department in 1966 and retired in 2011.

Ernest was one of the most popular teachers in the UCSB Humanities division and in the College of Creative Studies, attracting particularly inquisitive students to such courses as “The Power of Negative Thinking.” In 2001 Ernest was nominated by his students for an Academic Senate Distinguished Teaching Award. Everyone found him to be a mine of information on the leading figures in French contemporary philosophy and literature, most of whom he knew personally since he spent entire summers in Paris.

He was also especially appreciated for the high quality of his writing. While he was the world’s acknowledged expert on the 18th-century French novelist Crébillon fils, on whom he published three books, and contributed frequently to the debate over the importance of Existentialism, he did not confine himself to academic outlets. He published a novel (in French) and a play that was produced by the UCSB College of Creative Studies. He also translated into French two volumes of criticism by the Dean of Comparative Literature studies, René Wellek, both of which received great praise for the quality of the French prose. For his efforts on behalf of France, the French government awarded him a knighthood in the rank of Chevalier in the Order of the Academic Palms in 1991, and a year later he was elevated to the rank of Officer.

The academic life, in which he enjoyed so much success, played a secondary role in Ernest’s existence to the exercise of his fundamental principle: autonomy. He prided himself on scouting out all the hidden treasures of Paris, to which he then introduced his friends. His knowledge of Santa Barbara, from Montecito to Milpas, was legendary and facilitated by slow meanderings in his car, whether the old station wagon with holes in the floor boards, or the shiny new Prius. He would also attend many musical events in the Santa Barbara area because he was an accomplished pianist and lover of the classics.

Ernest was a “character” in the best sense, a brilliant mind occasionally put to the service of hilarious pranks. He was unforgettable as a mentor, a friend, and a colleague. He is survived by his wife Fuka, her son Boris, his wife Marie, and their two children who will miss him mightily.