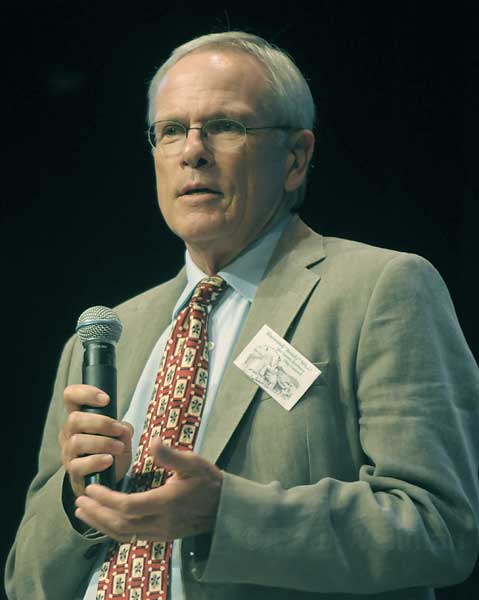

Harwood “Bendy” White

2009 City Council Candidate Profile

Harwood “Bendy” White is the classic Santa Barbara insider who’s long played the role of loyal opposition. A third generation Santa Barbaran, White, whose uncle – noted author and high profile Santa Barbara resident Stewart Edward White – shot wild game with the likes of former President Theodore Roosevelt, served 14 years on the city’s Planning Commission and eight before that on the Water Commission. While on the Water Commission – where White frequently butted heads with city administrators – he helped City Hall weather a storm of frightened and angry water customers during the drought of the late 1980s. As chair of the commission, White’s political magic lay in his ability to listen forcefully. People left having been heard. (On the campaign trail, however, White’s proven indifferent at walking precincts and at forums, too soft-spoken to emerge from a pack of 13.)

During his tenure on the Planning Commission, White – a land use agent by profession – was given the nickname “Doctor No” not-so-fondly by developers and city planners because of his propensity to vote against projects. But White’s dissents were notoriously thorough and civil. Typically, he’d present a laundry list of improvements he thought were needed. Just as typically, he’d get some, but not all. His fellow commissioners would vote for the project; often he’d vote against. “That form of sausage-making kept me from becoming a total wing-nut,” he said. (On Veronica Meadows, White was adamantly opposed to anything that might intrude into what he terms “the lungs of Santa Barbara,” and vigorously tried to kill the project from the start.) More than any specific concessions obtained, White said he’s proudest of injecting discussion, debate, and disagreement into an institutional culture that placed an unhealthy premium on unanimity for its own sake.

Those skills will be sorely tested should White, now making his first bid for elected office, win a seat on the City Council. A self-described social liberal and fiscal conservative, White expressed astonishment that the council would approve any pay increase – no matter how small – during the depths of the recession. Voters, he said, were justifiably upset that the council burned through 90 percent of the $10 million reserves that had initially been set aside for bad times. “This council has caved into [City Administrator Jim] Armstrong and staff and let the citizens down,” he said. “But I worry that the reaction to it will be far too draconian. That’s what I see myself getting into the middle of.”

The reaction to which White referred was the slate of candidates backed by Randall Van Wolfswinkel, and the angry conservative tone White says they bring to the debate. White helped craft Measure B – terming Santa Barbara’s historic character “our bread and butter, our croissant” – which Van Wolfswinkel has embraced. But White earned the enmity of Van Wolfswinkel by working as a private land use consultant for developer John Price in his bid to build a three-story mixed-use development at the present site of the Union 76 gas station in Montecito. Van Wolfswinkel helped bankroll the opposition to that project. White recused himself from deliberating on that project, now the subject of an ongoing legal challenge. Opponents have expressed concern that White’s consulting work could constitute a conflict of interest.

In response to city budget deficits, White said all the easy budget cuts have already been made. “The only thing left is meat and bone,” he said. There may be too many planners in the Planning Department, he said, too many traffic engineers in Public Works. Salaries paid to public employees making six figures or more need to be cut back more. “However we do it, we best be listening in such a way that both the staff and public feel they’ve been treated fairly,” he said, “because real pain and real sacrifices are in the works.”

On gangs, White said City Hall needed a Latino to serve as its Gang Czar. “Somehow I don’t think folks will be looking to the gringos for leadership on this one,” he explained. (The current gang czar, Don Olson, is an Anglo.) White also suggested that City Hall should do more to nurture the development of neighborhood associations in areas that see the most intense gang activity.

On traffic issues, White is more of a pragmatist than a crusader. Car usage will vary directly to the price of gas, no matter what City Hall does or doesn’t do, he argued. In that light, he argued High Occupancy Vehicle Lanes would offer more immediate congestion relief than commuter rail could hope to. Likewise, the city should focus its support for MTD on getting quicker and more convenient bus service on the most heavily traveled lines, and not, he said, on routes taking riders to Orpet Park. White said he’d keep bulb-outs and roundabouts in his “tool box” of traffic calming devices, but stressed he wouldn’t support them unless the immediate neighbors wanted them.

On planning issues, White straddles the line between traditional slow-growth preservationists and the new high-density urbanists. As a result, he is liked, respected, but also wondered about by people in both camps. On the campaign trail, White is quick to cite his role in giving birth to Measure B. He also adds that the ordinance by which building height is now measured should be changed to give architects more developable space. Otherwise, he warned, all new buildings will have flat, boring, monotonous roof lines. This change would effectively increase the maximum downtown building height beyond the 40-feet called for in Measure B. White concedes Measure B is hardly a perfect planning tool. But the council, he said, refused to take action when he and fellow and planning commissioners Bill Mahan and Sheila Lodge – to name a few – warned them there was a problem that needed fixing. White also acknowledged that he approved two of the Chapala Street structures that gave rise to Measure B in the first place. On one, he said, he was snookered. On another, he said, the developer offered set-backs away from Mission Creek far beyond what city ordinances required.

White supports high intensity development focused along transit corridors, now regarded with suspicion and hostility by traditional slow-growthers, and would love to see a major mix of commercial and residential development proposed at La Cumbre Plaza. The real cutting edge planning question was how to limit developers from building luxury condos downtown. “That’s what the market wants to do: Build high end condos. But we need units to be much smaller than what we’ve been approving,” he said. “The question is how do we get there?”