A Bridge Is Burned

Former UCSB Museum Curator Speaks Out

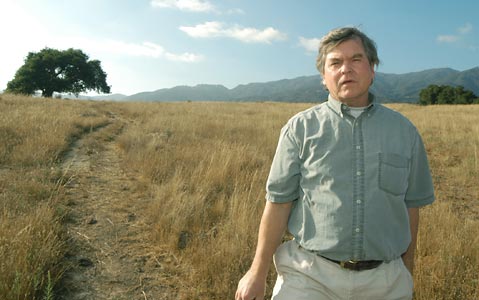

Mark Holmgren is out of a job, but he’s okay with it. What burns him is that his old staff position at UCSB — Vertebrate Collection curator — no longer exists, and the recent decision to eliminate it was, he feels, shortsighted and ill-informed. The longtime environmental advocate and academic — whose creative conservation strategies over the years have garnered him a somewhat roguish reputation around town — is well aware that budget cuts to the UC system are widespread, and that departments have had to downsize across the board. But he insists his old job played a unique and crucial role within Santa Barbara that will be sorely missed by students, area residents, and the scientific community at large — if not the university — and that other unspoken factors other than budget constraints led to its demise.

With more than 33,000 specimens in its vaults below Harder Stadium’s bleachers, the Vertebrate Collection, says its former curator, is an invaluable resource. It houses not only preserved birds, mammals, reptiles, and amphibians, but also maps, photographs, and carefully compiled research on area ecology that is constantly referred to in preservation as well as development projects. The collections, Holmgren explains, are not unlike a large library that has been carefully compiled over a number of years, and represent an “incredible inheritance of nature” from the tri-county area. “It’s simply a treasure to be able to reach into and extract information and insight,” he said. “It gives you direction and understanding of what is out there.”

Holmgren explains how, by unraveling data stored within the museum, he’d often help local restoration projects become much better equipped and informed in their goals. To help preservationists determine how and why an area may have degraded, Holmgren and his colleagues, notably biologist Wayne Ferren, would dip into the collection to see what once lived and thrived in the area. Preservationists would often use that as a target for restoration. “On the other side, if you’ve done the restoration,” Holmgren went on, “you have the expertise to evaluate whether that restoration has met its goals.” He pointed to a UCSB professor who’s currently using the collection to track the first signs of chytrid fungus in the area — which is killing amphibians worldwide at an alarming rate — in preparation for possible repopulation studies.

But without a seasoned and knowledgeable curator, an impassioned Holmgren argues, it becomes difficult to effectively help others tap into museum resources. While two undergraduates — quickly trained by Holmgren prior to his departure — have been assuming curator roles in a very limited capacity since he left, he said, they can’t expect to match his breadth of familiarity and experience with tri-county biology; he’d been at the university for over 25 years.

Carla D’Antonio, faculty director of the Cheadle Center for Biodiversity & Ecological Restoration (CCBER) — the facility which oversees the vertebrate museum as well as a number of other collections — agrees. She said, “He was a great, great resource and it’s going to be tough without him,” and explained that the decision came down from the department of Ecology, Evolution and Marine Biology (EEMB) which oversees CCBER. Holmgren took pains to emphasize that he doesn’t think he’s the only man for the job, but that it’s the erasure of the position that worries him. “I’d be perfectly happy, by the way, if someone came along who could play this role,” said Holmgren. “I’m of retirement age anyway.”

Beyond managing the museum (and conducting tours and outreach programs with area schools), Holmgren also fulfilled a generally undervalued but controversial role within the university. Acting as a bridge between academia and concrete governmental oversight, Holmgren would teach student interns how to craft their passion for ecological restoration into arguments for or against policy changes and land use decisions. Shepherding students through the often complicated and intimidating world of local government, he would teach them how to communicate in such a way that their ideas and concerns would be taken seriously by policy makers, including county supervisors and city councilmembers.

However, said Holmgren, his guidance was not something the university cared about or appreciated. “The connection of natural resource information to public policy concerning the environment is not valued at UCSB,” he asserted. “This not a recent trend. It is a pervasive omission whereby the whole connection of the education system to this part of our government that regulates and oversees natural resources is lacking.” UCSB’s student body, a large portion of which is highly concerned about the environment and the animals in it, is grossly unprepared to assume positions within regulatory agencies because, Holmgren contended, “There has never been an effective method at UCSB of reaching into policy and emphasizing [it], and training people.”

“I’m concerned,” he went on, “because we had an effective bridge through the CBBER Museum of Systematics and Ecology, vertebrate museum, and herbarium from the early 1980s until the early 2000s.” He said, “That bridge has slowly eroded, beginning with the loss of Wayne Ferren, and what we’ve lost is a 30-year commitment to … connect town and gown.”

CCBER and EEMB insiders, for their part, say that while Holmgren was well-liked on a personal level, some found his unorthodox approach to his job disquieting. His bosses reportedly had a tough time pinning him down over the course of any given day — as he was commonly out in the field, kept odd hours, and was typically late to meetings — but his interns had nothing but overwhelmingly positive things to say about his guidance and attention. All parties asked to be kept off the record, and CCBER declined to follow up on requests for a tour of the Vertebrate Museum. Holmgren wasn’t able to conduct a tour for The Independent himself because of where things stand with his labor union and the school’s Human Resources department.

UCSB faculty, Holmgren contended, who individually oversee the collections, don’t interact with the resources and material on the same meaningful level that he was able to. They are “hands-off and disconnected,” he said, explaining that when faculty failed, in his eyes, to set the record straight with county electeds and other officials over tri-county land use issues, he would step in. “The kinds of things we’d get involved in generally were the ones that were so divorced from ecology and land-use planning that we felt we needed to point out that discrepancy … Faculty don’t point it out even if it’s direct conflict with what they’re teaching in a class. They tended to not say anything. They’re just concerned with bringing their next grant in and getting their next pay raise. There’s a matter of courage going on here, and most faculty don’t have the balls to show it because they really depend on their advancement in terms of the system they’re involved in.”

Because the university doesn’t view the vertebrate collection as a moneymaker, the former curator said, it is less inclined to spend any cash on its upkeep and management. Without hard numbers to point to — definitive future payoffs of initial investments — the institution sees it as less valuable than, say, a materials science program that will hypothetically yield a 300-percent payoff in a five-year period, said Holmgren.

However, Holmgren — who was working half-time and was reportedly paid a yearly salary of $30,000 — claims there was more than this fiscal logic that led to his job’s elimination. The decision, he claims, may have been rooted in a longstanding desire to quiet his tendency to speak up against UCSB development plans. For example, he got very publicly involved in the university’s south parcel project: UCSB’s proposal to build on the triangle of land in between Coal Oil Point Reserve and Ocean Meadows Golf Course “didn’t make any sense,” Holmgren said. “You have a reserve here, and a golf course on the other side that might one day turn back into an estuary. Why would you put a development between the two instead of maximizing the open space connections? It’s a huge problem of fragmenting viable habitat for plants and animals. We said this is against everything that’s taught.”

Holmgren, referencing his one-on-one teaching of interns, lastly mused, “The university might not want this stuff to be taught because [we] are the people who were influencing the outcomes on the development agenda. That’s the subtlety; that’s at the core,” he said. “This may have been a long-term objective.”