From Louisiana to Minnesota to Dallas to S.B.

Law Enforcement Officials and Activists Respond to Three Tragedies

As the nation watched in horror the July 7 tragedy in Dallas, reactions poured in from Santa Barbara activists and law enforcement officials, who found themselves reeling from two police killings of African-American men earlier in the week.

Alton Sterling was the first to go. Early on July 5, outside the Triple S convenience store in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Sterling, 37, was shot to death when police responded to a report of a “black man with a red shirt selling music CDs,” who had reportedly threatened the caller with a gun, reported the New York Times. At least two cell-phone videos taken by bystanders depict two officers pinning Sterling to the ground, where he was shot six times — twice in the chest.

The next evening, 32-year-old Philando Castile was stopped for a broken taillight by two police officers in a suburb of St. Paul, Minnesota. His girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds, livestreamed his death to Facebook in a 10-minute video in which she says Castile informed police he was licensed to carry before they asked him for his ID card. When he reached for his ID, she said, he was shot four times.

The shootings in Louisiana and Minnesota brought the death toll of African Americans at the hands of law enforcement officials to 136 this year, according to a project by the Guardian. That number has since climbed to 144 as of press time.

Then, on Thursday, July 7, five Dallas police officers were killed when Micah Xavier Johnson, 25, fired on them with a rifle at the end of a peaceful demonstration to protest police killings of black men. In the ensuing exchange of fire, seven officers and two civilians were injured. Johnson, an African-American man and a United States military veteran who had reportedly been planning the attack for some time, was killed hours later with a bomb carried by a robot after a standoff with police in a downtown parking garage.

Santa Barbara’s interim Police Chief John Crombach, whose department’s flag flew at half-staff on July 8, as did government offices’ across the country on President Barack Obama’s orders, called the Dallas shootings “unprecedented” in his 37-year career. “This is actually an ambush and open civil warfare on law enforcement in a major U.S. city.” The cities of Dallas, Baton Rouge, and St. Paul, he said, “have a big hole to dig out of,” an effort he believes begins with officers — when they interact with civilians — “taking the time to explain to people what [they are] doing and why.”

In an email to The Santa Barbara Independent, Santa Barbara County Sheriff Bill Brown said, “Let’s not lose sight of the fact that every day there are, literally, millions of encounters between American law enforcement officers and members of the public. If the media, and we as a society, choose to focus disproportionately on the tiny fraction of times when things go bad, we lose sight of the overwhelming majority of times when the police get it right — and when lives, property, and our way of life are protected.”

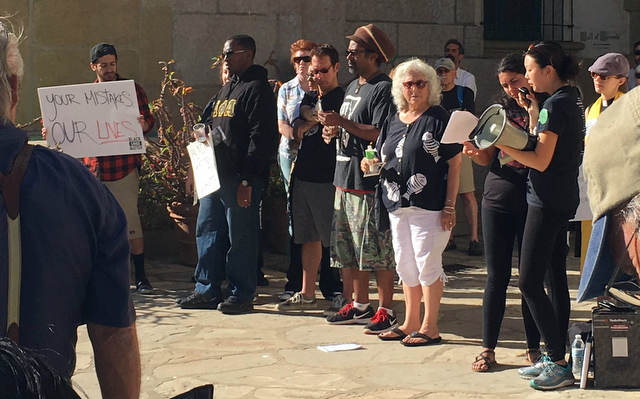

With the statement “standing up to police abuse does not mean you are anti-police,” the youth-oriented activist group PODER (People Organized for the Defense and Equal Rights of S.B. Youth) spread the word via Facebook for a Sunday vigil to “[d]emand that Santa Barbara Police commit to protecting Black and Brown lives.” (The group declined to comment on the incidents, citing insufficient time.) Organized by community leader Jordan Killebrew, SBCC’s Black Student Union President Chiany Dri, UCLA law student Dyne Suh, and UCSB sociology graduate student Zachary King, the peaceful gathering drew 150 people to a “holistic healing space” at the arch the Anacapa Street courthouse, said Killebrew.

Community members on Sunday held black-and-white pictures of black men, women, and children killed by law enforcement officials, which they placed — after each name was spoken — between paper-cup candles at the center of the group. The event, said Killebrew, in which attendees also spoke the names of the slain police officers, conveyed the following message: “We will stand up for justice, and we will protect our people.”

The day before, area activist Lizzie Rodriguez, Killebrew, and Dri had met with Santa Barbara City Mayor Helene Schneider, City Councilmember Cathy Murillo, city police Captain Bill Marazita, and Lieutenant Marylinda Arroyo to address racially biased policing in Santa Barbara County.

At a Tuesday City Council meeting, Rodriguez, Murillo, and Cheif Crombach said they are keeping open lines of communication, which incoming police chief Lori Luhnow reportedly intends to maintain. During public comment, a handful of community members — among them representatives of the Coalition Against Gun Violence (CAGV) and Just Communities — expressed support for “racial-ethnic disparity training” for city police officers.

Keith Terry, executive director of YStrive for Youth, Inc., said in an interview the “at-risk” young people he works with hate law enforcement officials because “they feel constantly like they’re being manipulated, abused, lied to, [and] embarrassed” by authorities. “They’ll approach them while they’re with their families and search them,” sometimes using excessive force, which, he said, is usually reported to no avail.

James McKarrell, Isla Vista’s Community Resource Sheriff’s deputy, has his own story of interacting with the police as a black child. When McKarrell was no more than 8 years old, he was playing cops and robbers around his Los Angeles home:

“I’m running around the corner and shooting at the bad guy — because I was always the good guy — and my mother comes running out of nowhere, and she’s screaming, and she’s waving her arms, and she pretty much tackles me. And she does that because LAPD, for whatever reason … they were on scene, and she saw me coming around the corner, and she saw those guys coming … Her fear was they wouldn’t recognize I was a kid, and they would shoot me … That was 30 years ago.”

Reverend Dr. David Moore, Jr., lead pastor at State Street’s New Covenant Worship Center, wrote on Facebook the night of the Dallas shootings:

“My heart is breaking. My 29-year-old son just texted me, ‘Is there a war between police and blacks?’ Then I remembered: when he was four years old he walked in to see me watching Rodney King being beaten. He asked, ‘Daddy, are they going to do that to you?’ I thought my kids would inherit a better world.”

Moore said in an interview, “Society needs the police as an institution, but we need them to be humane. We respect their badge; we want them to always respect their own badge.” He added, “Blue Lives Matter,” and that it’s important to keep in mind “it was the protesters who pointed out the location of the shooter.”