Mental Health Care Tops the List

Cottage, Neighborhood Clinics, Sanctuary Centers Focus on Filling Service Gaps

Barry Schoer got into the mental-health business about 40 years ago at one of America’s scariest psychiatric gulags, New York City’s infamous Bellevue psychiatric hospital. About 300 electroshock treatments were administered on a weekly basis, Schoer recalled; partial lobotomies were not uncommon. “And they used cattle prods to move difficult patients around,” he said. Bellevue took the patients who were floridly psychotic and gravely disabled. “It was really the worst of the worst.” As a technician, Schoer led group and individual therapy sessions; he also helped with the electroshock treatment. “We all got hit and slapped more than once.” Schoer lasted all of one year.

A sad-faced man incongruously graced with a salesman’s rat-a-tat ebullience, Schoer now runs Santa Barbara’s Sanctuary Centers. His harrowing journey down memory lane bubbled up during a grand opening tour last Thursday of the new Integrated Care Clinic located in a modest green cottage in Sanctuary Centers’ parking lot. The new facility will offer medical and dental services — provided courtesy of the Santa Barbara Neighborhood Clinics — targeting those with mental-health and addiction issues.

However unassuming, the Integrated Care Clinic will be the first of its kind in Santa Barbara and the only one between Los Angeles and San Francisco. As such, its opening was occasion for celebration. Amid balloons and proclamations from elected officials, Schoer described how a licensed therapist at the new facility would greet patients as they came in the door, gently quiz them on their mental-health circumstances, and offer to run interference with the doctors and dentists offering care. Over the years, Schoer recounted, too many of these patients had been told by medical professionals, “It’s all in your head; go see your psychiatrist.” Little wonder, he said, the mentally ill die 25 years younger than they otherwise would.

The small clinic fills a very large gap in services. And for Schoer and Dr. Charles Fenzi, chief medical officer for Neighborhood Clinics, it’s only a first step. Schoer has already applied for a special “population health” grant from Cottage Health not only to cover the cost of treatment but also to crunch the numbers to determine what works — and what doesn’t — in connecting the underserved with the mental-health care they need.

Although Cottage has yet to approve Schoer’s proposal, he’s already concocting plans to leverage those funds in applying for an even bigger grant from the federal government. This, he said, will enable him to triple the service capacity of the fledgling Care Clinic by building three dental and three medical offices. It’s possible that Schoer may have gotten out ahead of his skis on this, but given new revelations from Cottage Health on just how urgently additional psychiatric options are needed, probably not.

Cottage has chosen to focus its philanthropic punch on mental-health care like never before. This year, it actively solicited grant applications from 28 provider organizations in Santa Barbara County. As many as seven grantees will be selected, each receiving around $100,000. “This is the first year we are focusing almost exclusively on mental-health issues,” said Cottage CEO Ron Werft. “These grants will be the first real tangible thing to come out of the population health work we’ve been doing.”

Cottage took up the challenge of population health — exploring the social determinants of health-care access and outcomes — two years ago when the board changed its mission statement to include a commitment to what until then had been a hazy if trendy buzzword in health-care circles. “I got chills up and down my spine when the board approved that change,” Werft said.

Among public-health professionals, the concept of population health may be old hat. But for operations like Cottage and its three hospitals, it took on an immediate urgency with the passage of the Affordable Care Act and other lesser-known health-care reforms. That’s when the federal government put medical providers on notice they’d be paid not just for how many patients they treated, but for how well they treated them. Hospitals with high readmission rates, for example, would get paid less. High-sounding rhetoric about “prevention” and “continuity of care” all of a sudden had serious bottom-line ramifications.

Werft dove in headfirst. He brought national experts on the subject to Cottage for group brain dumps. Then he hired Elizabeth Majestic — who, with 24 years under her belt at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, qualified as a population-health rock star — to run Cottage’s own population-health initiative. For personal reasons, however, Majestic didn’t last long and was replaced by Cottage marketing czar Katy Bazylewicz — known more simply as “Katy B.”

With Katy B. running the show, Cottage hired a national polling firm to interview 2,500 county residents on personal behaviors that translate to health risk. It convened several stakeholder summits and conducted two dozen in-depth meetings with 230 community leaders and health-care professionals. Cottage was mindful of its reputation as the 800-pound gorilla in Santa Barbara’s health-care universe and knew that listening, rather than telling, was key. It also understood — given the area’s “ecosystem” of 1,800 nonprofit organizations — that the success of any population-health initiative depended heavily on successful collaboration.

“Cottage has the respect and the clout to get a lot of people sitting around the same table at the same time,” said emergency room physician Jason Prystowsky, also active with Doctors Without Walls, which offers care to people on the streets. Even more effusive is Dr. Charity Dean, a high-ranking medical professional with County Public Health: “It’s not every day all the leaders in Santa Barbara’s health community sit down together at the same table. Ron Werft’s leadership helped make that happen. His passion went beyond the issue of reimbursements.”

Werft said the preliminary polling and research highlighted striking differences in access to health care and outcomes based on race, ethnicity, income, and education. “We started to see some real discrepancies,” he said. “One of the biggest was whether you graduated from high school or not. That was huge.” Latino respondents were about twice as likely to report having diabetes as whites. They were three times more likely to report housing insecurity and twice as likely to report food insecurity. And they were 20 percent less likely than whites to have insurance and about 27 percent less likely to have a primary-care doctor.

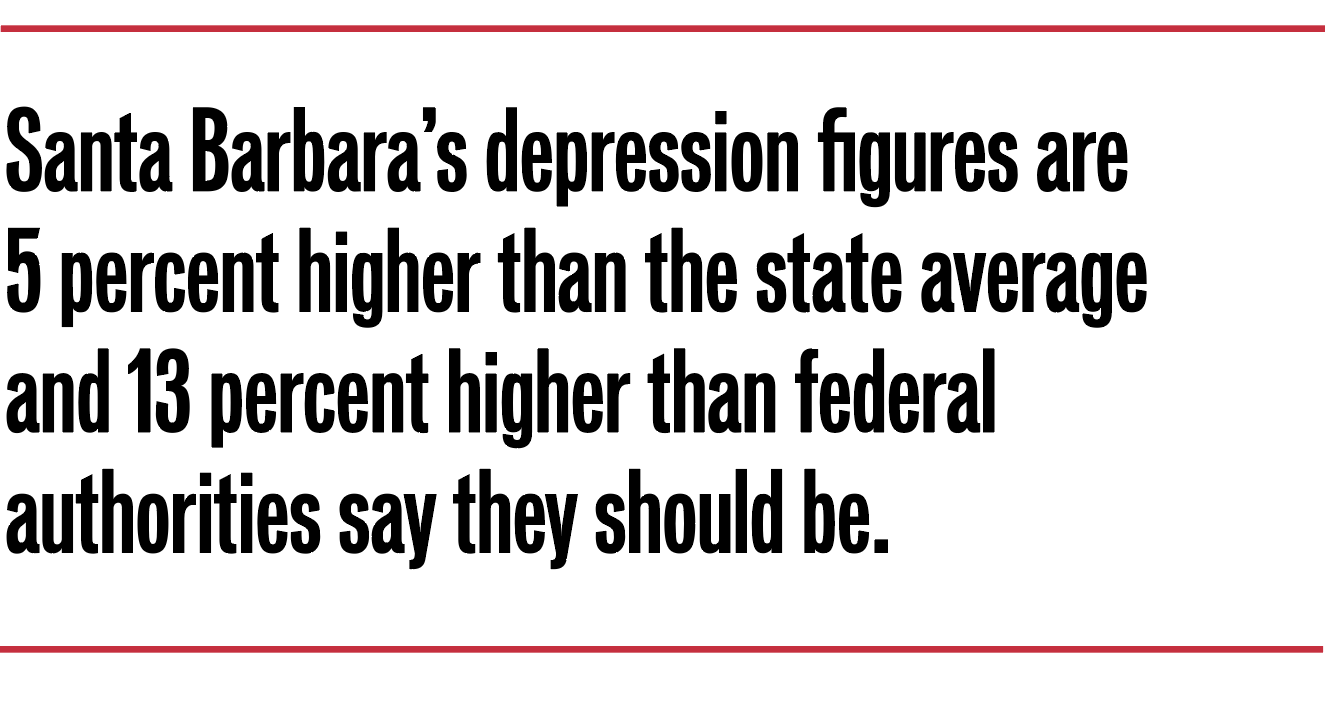

On the issue of mental health, however, that trend dramatically reversed itself. Thirteen percent of Latinos reported being diagnosed with depression, compared with 23 percent of whites. (Those numbers are highest among women, people between the ages 45 and 64, and those making between $35,000 and $75,000 a year.) Santa Barbara’s overall depression numbers were 5 percent higher than statewide averages and 13 percent higher than what federal health authorities say the numbers should be.

Making sense of those numbers, however, is another matter. According to Werft, “We’re unsure if there’s more depression here or [if] there have been more people diagnosed with depression.” Prystowsky calls depression the “silent plague of this generation,” adding that there are a “dizzying” number of possible explanations, from the degradation of community to increased prevalence of social media to the economic pressures of staying alive. “This is the stuff of a PhD thesis,” he said. As for the ethnic discrepancies, most health professionals believe Latinos are culturally less likely to admit to depression or to seek treatment.

Much more clear, however, was the sense of urgency expressed by the 230 community leaders who participated in the listening tour. Mental health ranked at the top of 12 categories of concern, 11 percentage points higher than the next on the list, “Housing insecurity.” Only 13 percent of participants thought there were adequate resources to deal with the community’s mental-health needs.

Cottage itself took criticism for not doing more. “Of note, Cottage’s perceived role in creating this shortage came up several times,” a summary document stated. In the midst of the listening tour, then–county supervisor DoreenFarr had publically called out Cottage for not making detox beds available to Medi-Cal recipients. Cottage had stopped providing acute-care psychiatric beds to county Medi-Cal recipients in 2007, citing annual losses of $800,000 a year. “The gap in what it cost to provide the service and what we got in reimbursement just got too large,” explained Werft. “And our psychiatrists no longer supported the program.”

As has frequently been reported, there are only 16 beds in all of Santa Barbara County available to those placed on involuntary holds. The cost to the county — and the downstream consequences caused by this shortage — have been the subject of intense concern among mental-health officials, who spend millions annually shipping patients to out-of-town facilities. “The number one reason for out-of-county patient migration is involuntary care,” Werft declared.

Werft said Cottage has felt the immediate impact of the mentally ill on its emergency rooms. In response, it opened up a separate emergency psychiatric wing three years ago. Since then, Cottage has seen a 65 percent reduction in its number of involuntary holds. Prystowsky lauded such moves, but added, “It’s kind of like building a bigger jail. We want to get to a place down the road where we’re sending fewer and fewer people to the emergency room. I’m an ER doc, but the day I’m out of work will be a good day.”

Werft stressed that collaboration will be vital to any broader response to Santa Barbara’s mental-health challenges. Cottage can’t do it alone. Partners like the Santa Barbara Neighborhood Clinics have already stepped up efforts to integrate mental-health treatment into primary care visits — hiring a bilingual, bicultural psychiatrist from Texas and assigning two licensed social workers to help. That’s enough hours to ensure that four of the neighborhood clinics have mental-health providers on hand at least two days a week.

In the meantime, Cottage is planning to expand the respite care provided to homeless people who are too sick to be released from the hospital but too well to stay. Some of these patients, Werft said, wind up in Cottage’s Emergency Room as many as 50 times a year. Many of them have long-standing mental-health challenges.

Cottage hopes to encourage collaboration with Santa Barbara’s legion of nonprofits by releasing much of the data its population-health team amassed through the free website cottagedata2go.org. On it, the county is broken down by 87 census tracts and 26 distinct geographical entities, with health, education, income, crime, and political data sets for each. Cottage is hoping the information will help community organizations submit more data-driven grant proposals in terms of their target populations and what they hope to achieve. Likewise, it’s hoping that subsequent grant evaluations will be similarly rigorous in detailing what was actually accomplished. “Inevitably there are going to be some swings and misses,” said Werft. “But now is the time do something. How we actually do, we’ll know better in about two years.”

For Barry Schoer of Sanctuary Centers, there’s no shortage of gaps to be filled. The county’s Department of Behavioral Wellness serves only those experiencing serious distress. For those experiencing mild to moderate challenges, the resources available are often baffling to nonexistent. Patients seeking a first-time appointment with Sansum psychiatrists, for example, are told to wait until 2019, and insurance coverage is spotty even for those with policies.

In the short term, Schoer remains thrilled with the grand opening of the new Integrated Care Clinic. It’s not reserved only for those with mental illness, he stressed, but it definitely targets that critically underserved population. It’s been a long and winding road from Bellevue Hospital to his Santa Barbara clinic. In that time, treatments available to the mentally ill have gotten infinitely better, if access remains at time perilously elusive. Likewise, it’s been a long time since Schoer has been socked or slapped by a patient. But based on the sign on the new clinic door, he’s not taking any chances. It reads, “No guns or weapons allowed on the premises.”

This article emerged out of a fellowship Nick Welsh has had with the USC Center for Health Journalism.