Restaurant Reopening Reality Check

Santa Barbara Restaurateurs and Officials Explore Creative Solutions to Pandemic Dining

By Matt Kettmann | Published on May 21, 2020

I’ve never known Mitchell Sjerven to be a dour man, even during past disasters and downturns. But today, clouded by the coronavirus pandemic’s relentless uncertainty, there’s an unquestionable level of angst in the veteran restaurateur’s voice when he talks about the future of bouchon, the West Victoria Street fine-dining establishment he opened in 1998, as well as the 400-plus other restaurants across Santa Barbara.

“We were geared up for what probably would have been our best Q1 ever — then we came to a screeching halt,” he explained of closing the restaurant on March 15 and sending his team of 23 home with care packages from his unsold supplies. His team investigated doing takeout and delivery, but that makes little sense, economically or qualitatively, for a white-tablecloth restaurant.

Instead, Sjerven — who’s also taught restaurant ownership for SBCC’s School of Culinary Arts since 2009 — is saving money on utilities, dipping into his bank account to pay rent, and trying to figure out how he can use his PPP loan, itself a confusing conundrum of short-sighted legislation for most restaurants. “The hospitality, restaurant, and leisure sectors are all hurting hard, and that’s people, not money,” he said of the shutdown’s human impacts, which are compounded in his neighborhood, where all of the nearby theaters shuttered as well. “We’ll drain our savings until the willpower disappears.”

Most critically, like business owners from Long Island to Long Beach, he’s preparing to reopen his restaurant. But despite state guidelines that were issued last week and federal and county guidelines that came out this week, no one really knows when that will be or what that will look like.

The state is allowing certain counties to open restaurants and other businesses if they meet thresholds for new COVID-19 cases and deaths. Until this week, Santa Barbara County’s tally was being hampered by the outbreak at the Lompoc penitentiary. But on Monday, after relentless lobbying by regional politicians, the state agreed to decouple those numbers from the county’s, meaning reopening could come soon.

When restaurants do open, diners can expect to see plenty of masks, gloves, and sanitizer bottles. Physical distancing rules may also mean plexiglass partitions and, almost certainly, greatly reduced capacity. Given that most restaurants already teeter on razor-thin margins, cutting sales in half just won’t work out.

“We want to be able to open in a manner that’s safe for both our guests and our staff,” said Sjerven, echoing every restaurant owner I’ve spoken to. But he hopes it comes soon. “We can’t keep our heads down forever,” he said. “It’s taxing, and I think the toll it’s taking on our society as a whole may end up being more costly than anyone is acknowledging right now.”

Somewhat paradoxically, the number-one fear hovering above Sjerven and the entire industry is that reopening will cause a surge in new COVID-19 cases, triggering a second wave of shutdowns. “That would be the death knell for tons of restaurants and other small businesses, too,” said Sjerven, who said reopening costs are similar to starting a new restaurant from scratch. “It’s one thing to fingernail it and get back up and running. But to close down two to four weeks later? Where do you get the money to try to reopen after that? That’s when reopening would cost more than remaining closed.”

High Stakes on Steaks

The stakes are incredibly high in Santa Barbara, where tourism traditionally picks up so many tabs. According to Visit Santa Barbara, dining at restaurants is the number-one thing that tourists do when they come to town, with 71 percent of visitors in a recent survey saying so — that even beat out our beaches, which only got 55 percent. Restaurants and bars are also one of the region’s largest employers, with about 5,000 jobs estimated to be in the sector in the city alone.

Unfortunately, the federal Paycheck Protection Program, or PPP, doesn’t work well for all restaurants. “PPP has been helpful to a lot of restaurants, but it’s also handcuffed a lot of them — it’s an eight-week fix for what is going to be an 18-month issue,” said Greg Ryan of Bell’s in Los Alamos, which was one of the 80 founding establishments behind the Independent Restaurant Coalition. “The IRC is working very hard to make people understand that there needs to be some carved-out money for restaurants of a certain size that will sustain them as they start to move into different models.”

Fortunately for restaurateurs, both the City and County of Santa Barbara reacted quickly to develop creative solutions. Both launched task forces with business owners and policy makers, who are meeting regularly and with extreme urgency. On Friday, May 15, after 27 meetings with more than 350 individuals, the county unveiled its 80-page RISE (Reopening in Safe Environment) Guide, designed as a supplement to the Resiliency Roadmap that California Governor Gavin Newsom unveiled earlier in the month.

The city is moving even more acutely. On Tuesday, the city council approved a plan to shut down vehicular traffic on the 500 and 1200 blocks of State Street. A forthcoming ordinance will allow restaurants to expand their seating onto the sidewalks, parking lots, and even the street, where appropriate.

It’s not a new idea, as shutting down State Street has been bandied about for years. But, as Nina Johnson, Santa Barbara’s senior assistant to the city administrator, explained, “The pandemic is giving us a compressed timeline to plan out and reenvision downtown.”

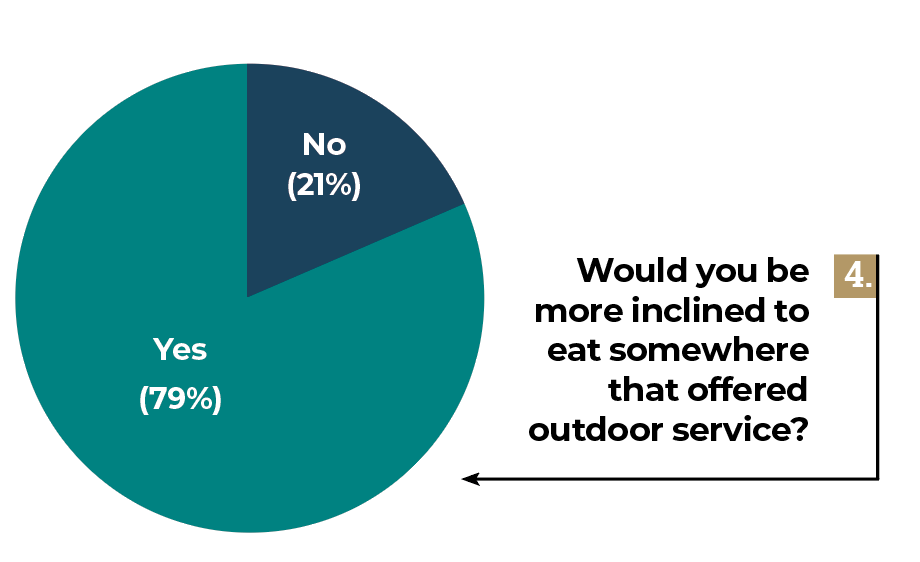

Her colleague Jason Harris, who started as the city’s first-ever economic development manager amid the pandemic on March 30, believes Santa Barbara is ideal for this solution. “We are a very fortunate community to have the climate to support outdoor dining, at least for the foreseeable future,” said Harris. “It would allow restaurants to augment the reduced capacity on the interior premises. And as we know with the virus, it’s much better to be in the open air from a public-health standpoint.”

Sherry Villanueva, the owner of Acme Hospitality, which runs The Lark, Loquita, and other restaurants, is encouraged by the city’s progress. “We’re not interested in jeopardizing public health and safety, so if that means taking 50 percent of my tables and putting them in the parking lot, then everybody is happy,” explained Villanueva. “Is it going to meet the needs of all 402 restaurants? No. There are going to be some that have nowhere to expand.”

For those who can, Villanueva believes that, with the city’s support, both the state alcohol regulators at the ABC (Alcoholic Beverage Control) and the county’s health watchdogs will allow these expansions very quickly. (In fact, on Monday, the ABC unveiled the Temporary Catering Authorization to allow for outdoor expansion of licenses.) “It should not be that hard,” she said. “This should be a piece of cake.”

This sort of relief couldn’t come soon enough, even for a successful restaurant group such as Acme. Villanueva’s establishments have started, stopped, and restarted takeout/delivery in the past two months, and her chefs are helping to feed homeless people, seniors, veterans, and others in need through partnerships with the Foodbank of Santa Barbara County and the Community Food Collaborative.

“I’m not exaggerating — I have been working 15 hours a day seven days a week going into my ninth week straight,” explained Villanueva, who’s on pandemic subcommittees for both the county and city. “I don’t say that with pride. It’s unsustainable, but you’re desperately trying to create a survival strategy for your business. You’re trying to be a banker and a CPA and a therapist while preparing food for 200 people every week.”

Grave New World

For those establishments that won’t be able to rely on the outdoors, the restaurant dining experience of 2020 to come won’t be anything like it was three months ago. Marge Cafarelli, the owner and developer of the Santa Barbara Public Market — where 500 people could congregate over noodles, tacos, pizza, beer, and bubbly in the past — is taking a firm stance when it comes to public health.

“My situation is a little different than other restaurants: You walk into a very large space with multiple restaurants,” she said. “I have to control that space. That could be fertile ground for the coronavirus for a whole host of reasons. It’s incumbent upon me, not only as a landlord but also as a business owner, to take the steps to protect against what I don’t even know might be out there.”

She’s always prided herself on keeping the food hall clean but is now upping that game considerably. Starting this week, she is mandating all of her tenants and employees to take each other’s temperature and check for COVID-19 symptoms before starting their shifts. She will expand those protocols to the general public when we are allowed back in.

She’s also drastically reducing the 350 seats and spacing everything out in line with the physical-distancing guidelines and is putting up plexiglass in strategic spots. The Chapala Street door will be for emergency exits only so as to better track occupancy coming in the main entrance, and she’s turning the air conditioning down and off in some spots, to ensure less coronavirus-spreading air flow.

“This is not going to be easy,” said Cafarelli. “It’s going to be fluid. It’s going to be a work in progress. Some things may work; other things may not. We have to be smart about how we reopen so that we don’t have this massive reinfection.”

How effective any of this will be toward that goal remains unclear. “The reality is that this is all theater,” said Cafarelli. “Our guests have to use common sense about how they do this.”

Optimistic Cherry on Top

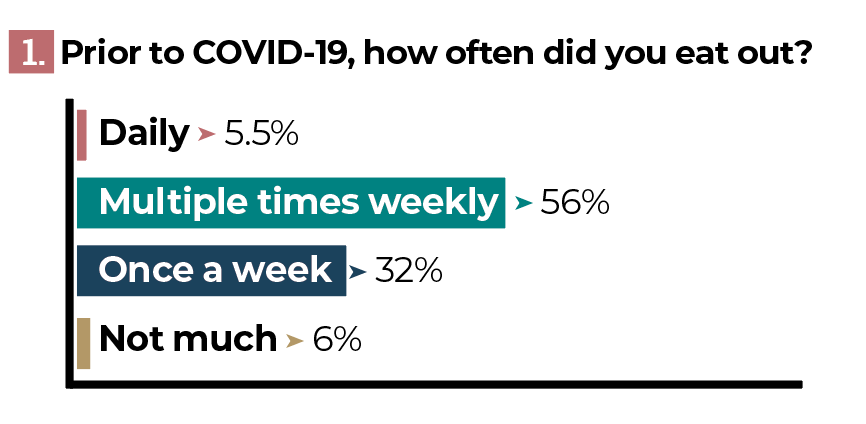

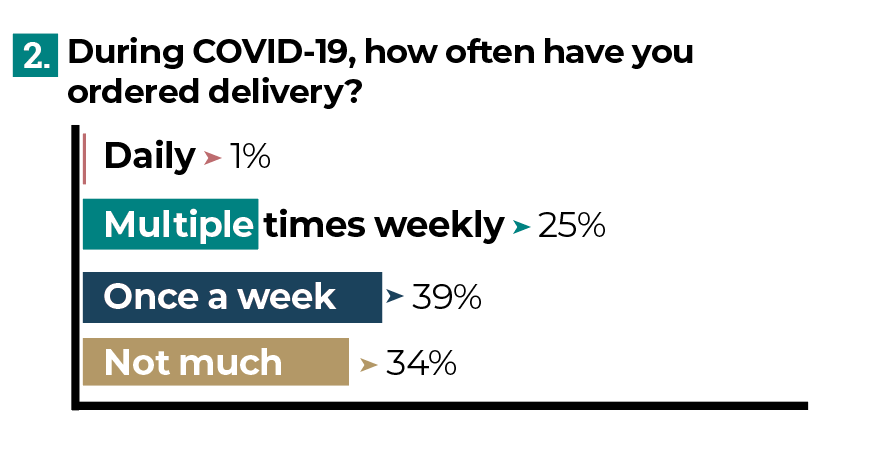

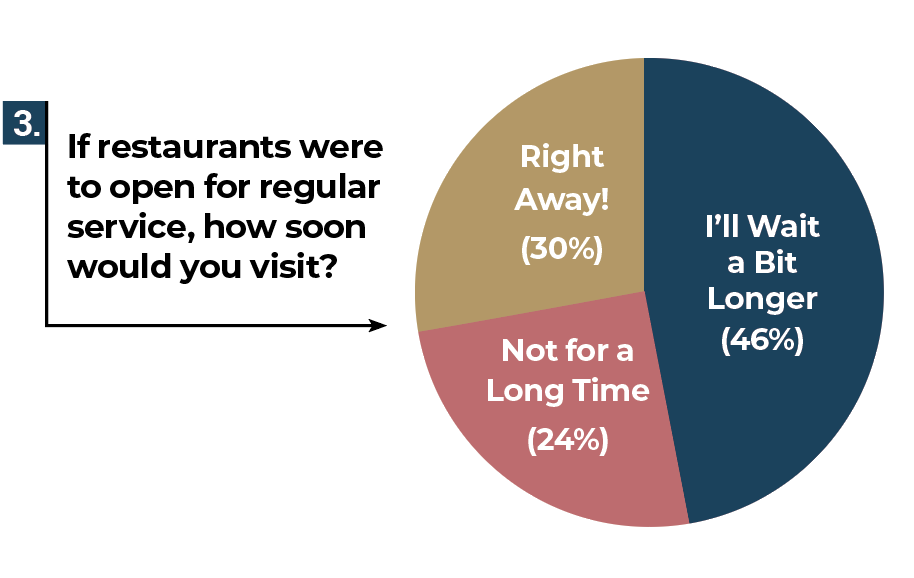

To gauge how ready our readers are to return to restaurants, whatever they look like, the Santa Barbara Independent ran a week-long survey via Independent.com.

Of the more than 1,200 responses, of which 95 percent ate at restaurants at least once a week prior to the pandemic, the primary takeaway is that 30 percent are ready to go back to restaurants right away, and that nearly 80 percent would be more inclined to sit outside. The survey also asked what diners will expect to see as the pandemic winds down: masks, sanitizer, contactless ordering and payment systems, and, most of all, reduced dining capacity scored highest.

“Do you really want to sit at bouchon for two hours under those circumstances? It doesn’t sound fun,” explained Sjerven. “We’re not selling food and wine. We’re selling an experience that people enjoy lingering over.”

He’s preparing nonetheless — his daughter, Caroline, whom he whisked from her college studies in Paris as the pandemic grew, is now sewing “designer bouchon face masks,” reported Sjerven, with a glint of hope. “We’re gonna make the best of it.” Even better news: “Someone made a reservation for Thanksgiving yesterday,” he said. “That made my day.”

While the immediate future remains hazy at best, there is a strong belief that restaurant life will one day return to some semblance of normal, even if that means waiting for a vaccine. “I believe in my heart that, since the beginning of time, humans have been gathering and celebrating around food,” said Villanueva. “It’s not just a trend. It’s something that is part of the culture and experience of being an interconnected human family. I just think that’s never going to go away.”

The Independent’s Restaurant Survey

What About Bars?

Unless they serve food, cocktail bars, breweries, and wine tasting rooms are not part of the state’s restaurant-reopening conversation right now.

“We’re concerned that bars, breweries, wineries, and such that don’t serve food are being separated from the restaurants for this phased reopening, and that makes us super nervous,” said Brandon Ristaino, who owns The Good Lion, Test Pilot, and Shaker Mill bars in Santa Barbara. “For me, there is no difference between the presence or absence of food when it comes to your risk of being infected.”

While Shaker Mill is connected to the food service at Cubaneo and has been doing takeout cocktails for two months now, he’s working on contingency plans for his other two bars: adding Sama Sama Kitchen menu items for The Good Lion and possibly Corazon Cocina from The Project for Test Pilot.

He has an “unshakable belief” that the culture of craft cocktails made carefully with real ingredients won’t be killed by COVID-19. “The cocktail bars and restaurants of the future will be the cocktail bars and restaurants from three months ago,” said Ristaino. “It might take a year, but I’m 100 percent certain we will get there.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.