Keeping the Game of

the Gods Alive

‘Pelota Mixteca,’ a Sport with Ancient Roots,

Thrives in Santa Barbara

By Ryan P. Cruz | Photos by Ingrid Bostrom | March 23, 2023

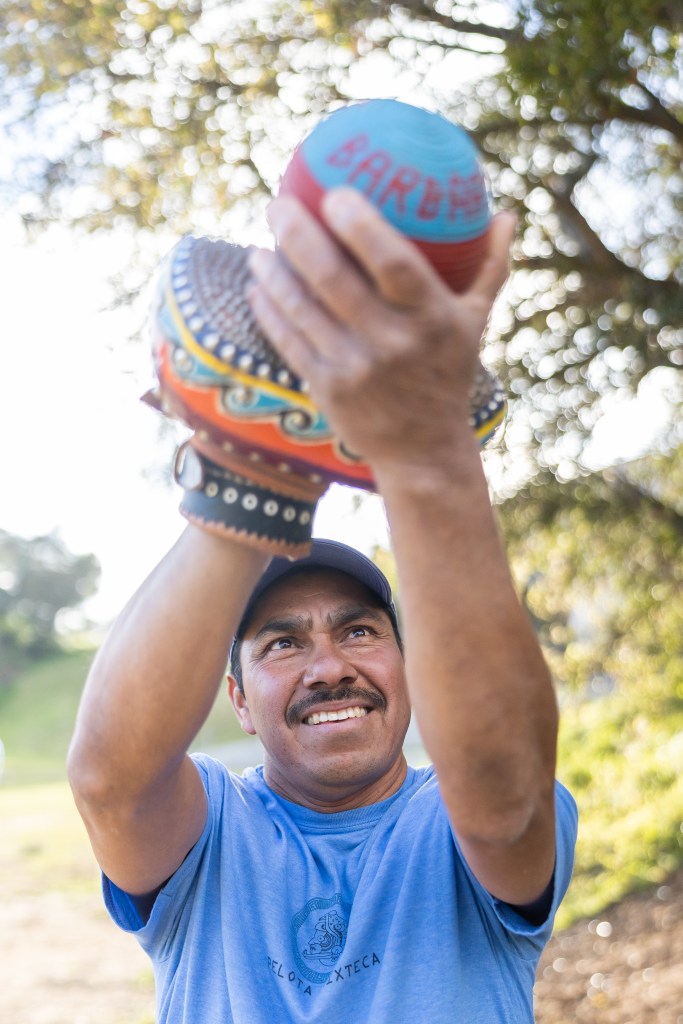

FLY BALL: Venancio López launches the ball to the opposing side. During matches, players will smack the ball hundreds of feet in the air across the field. | Credit: Ingrid Bostrom

Pelota mixteca, an ancient ball game with roots stretching back thousands of years and thousands of miles to pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica — a sport nearly snuffed out of existence when the Spanish took control of the region in the 16th century — is alive and thriving here on the Central Coast, thanks to a group of locals who brought the tradition with them to Santa Barbara from Oaxaca.

LOS AMIGOS PELOTEROS: Santa Barbara’s pelota mixteca team, from top left, Esteban Castillo, Venancio López, Genaro Cruz, Ramon Cruz, Ernesto Garcia, Julio López, Angel López, and Arturo Pacheco | Credit: Ingrid Bostrom

They call it El Juego de los Dioses, or The Game of the Gods, and it resembles a higher-flying five-on-five version of tennis, where instead of a racket, each player is outfitted with a 10-pound, metal-studded leather glove used to smack a three-pound rubber ball hundreds of feet in the air, back and forth in a dizzying spectacle of power and precision.

It’s a game full of legends and lore, where distinguished members of societies and warriors with names like Garro de Tigre (Tiger’s Claw) and Pata de Perro (slang for “barefoot,” because he played the game without any shoes) represented their territories in epic battles for power, and where modern Oaxacan pelota players are bigger than celebrities in their villages.

Here on the Central Coast, a team called the Santa Barbara Niños Triquis — a reference to the indigenous Triqui people from the mountainous region of Oaxaca — is keeping the pelota mixteca tradition alive, one week and one match at a time.

A New Generation

Santa Barbara resident Arturo Pacheco, who runs a gardening service in town, is passionate about pelota mixteca. Family and friends joke that he won’t shut up about it, but he just can’t help himself: It’s in his blood.

His father, Alberto “Don Beto” Pacheco Santos, and his uncle Augustín Pacheco Morga are the only two men in the world who make the sport’s iconic leather guantes; his grandfather Daniel Pacheco was among the early Oaxacan players to bring the sport back from the dead and into its current form.

When Pacheco was young, he remembers watching the men in his family play the game, and watching his father painstakingly craft and repair the gloves that came to define it.

After moving to Santa Barbara at the age of 15, Pacheco hoped to keep in touch with his roots by learning the game his father loved so much. A few other Santa Barbara residents with Oaxacan roots played the game as well, and soon the group was playing together every week and competing in tournaments with other teams from across California, Texas, and Mexico.

Now, the team has been playing together for more than 20 years, and they have built their own community, with brothers, cousins, and friends all learning the game and keeping the tradition going strong.

Out of the Ashes

Early depictions of the game — or at least the Mesoamerican predecessor of the game — can be found on the reliefs recovered at the Oaxacan archaeological sites Dainzú and Monte Albán, dating back nearly 3,000 years. There have been remains of more than 1,500 ball courts found throughout Mesoamerica.

KEEPING TRADITION: Arturo Pacheco keeps the family tradition with pelota mixteca. His father, Alberto, and uncle, Augustín, are the last remaining craftsmen of the sport’s unique leather guantes. | Credit: Ingrid Bostrom

Villagers played the game as a celebration of gratitude and as an offering to the gods for good rains and abundant harvests, according to descriptions written at the time. The game was also used in matters of social, political, and religious importance, where the outcome of matches could decide the fortunes of entire regions.

When the Spanish came to the region around 1520, their leaders considered the game evil, confused by the erratically bouncing rubber ball and confounded by the fact native peoples would spend hours playing the sport. They believed the players were practicing something “inhuman,” Pacheco said, and banned the sport along with many other traditional customs.

But the game survived, hidden away deep in the Oaxacan mountains where people had fled to escape Spanish rule. It was played in secret, with very few records of the game appearing until Mexico gained its independence in the mid-1800s.

“Once Mexico was free again, the game gradually began to be practiced freely,” Pacheco said. “It came out of the ashes.”

The game was soon restored in its place at the center of Oaxacan society, this time as the state’s favorite pastime, and as a way to celebrate a history that had nearly been erased under Spanish rule.

The Art of the Guante

El GUANTE: The handcrafted leather guante (glove) is iconic to the game. The gloves are made of layers of hardened rawhide and round-headed nails and can weigh between 7-12 pounds. | Credit: Ingrid Bostrom

As the sport regained popularity near the turn of the 20th century, it became more organized and more modernized. Quickly, the game spread into the valley and coastal regions, and then into La Mixteca Region, where it earned its modern name pelota mixteca.

Before that time, the game was commonly referred to as pelota a mano fría (cold-hand ball), and players would smack the ball with their bare hands. Then, according to legend, around 1910-1911, a player who sliced his hand working at a butcher shop wrapped a piece of leather around his wound to protect it during a match, thus spawning a whole new age of the guante.

Over the years, el guante de pelota mixteca, or the Mixteca ball glove, has transformed dramatically from that strip of leather into a handcrafted work of art, and the Pacheco family has played a pivotal role in its evolution.

The modern guante weighs anywhere from seven to 12 pounds — depending on the player’s position — and each glove is painstakingly crafted from layer upon layer of hardened rawhide stitched together and reinforced with hundreds of round-headed nails hammered into the face of the glove; with the finished product resembling a mix between a horse saddle, a studded leather belt, and a catcher’s mitt all rolled into one, then hand-painted with vibrant colors and patterns paying homage to traditional Mexican culture.

During the game, the glove becomes an extension of a pelota mixteca player’s body, Pacheco said. Their beauty lies in their function just as much as it does their form, and in the hand of an expert player, the heavy glove can be used to send the ball up as high and as far as a major-league fly ball.

Don Beto, Pacheco’s father, handcrafted each one of the gloves for the Santa Barbara team. Every glove is made specific to each player, taking into account their position, size, and their style of play. The colors and designs vary, some painted with pyramids, waves, or other animals (one player, nicknamed “El Chapulín,” has grasshoppers on his glove).

The process requires a skilled hand and enough strength to force a thick needle through inches of tanned leather. Don Beto and Augustín learned the trade from their father, Daniel Pacheco, who was part of the team in Oaxaca that helped revive and re-popularize the game in the 1930s. The two Pacheco brothers now live in Ejutla, Oaxaca, and are the only remaining glove craftsmen left. Neither has an apprentice, and with Pacheco thousands of miles away, there is fear that the craft may die with them, though their methods have been recorded in several books and videos.

Luckily, the gloves are extremely sturdy and can withstand years of abuse without much wear and tear. The hundreds of nails on each glove, hammered into the leather one by one, are extremely specialized and of limited quantity, and Pacheco’s uncle Augustín is noted to have the last remaining stock of nails left.

Throughout Oaxaca, the Pacheco family is well known for their craft, and the guantes themselves have earned a cult following for their unique aesthetic appearance.

How It’s Played

The game starts with five players on either side of the patio de pelota (ball court), a long stretch of dirt about 300 feet long and 30 feet wide. Each team has five positions, with each covering their own section of the playing field.

The server, el sace, begins each point by bouncing the ball off a stone near the center of the court and sending it to the other team’s side with a thwack of the glove. When the game starts, the players join together to yell their own version of “Play ball”: “¡Va de buena!” (“It’s going well!”)

Each team tries to return the ball to the other side with one clean hit, back and forth, higher and farther, until the ball either hits the ground more than once or leaves the playing field for a point.

Scoring is very similar to tennis: The first point is 15, then 30, then 45, then a “game” is won. Three games are a “set,” and the best out of five sets is the match winner. Matches can get extremely competitive, with teams competing for up to five hours to determine a winner.

After el sace, there’s el tage (second), el medio (middle), el resto (fourth), and el contrarresto (far back). Each position plays at a different depth, with many games becoming a display of long and soaring hits from one end of the court to the other.

Striking the ball is no easy task, but Pacheco said new players can learn how to adjust to the weight of the glove and the speed of the ball within a few months.

“A lot of people think you need to be strong,” Pacheco said. “You have to have power, but you have to be able to see how the ball is coming at you.”

Legends of the Game

In Oaxaca, pelota mixteca is king. Kids that grow up in the region look up to the ballplayers like role models, bigger than soccer or baseball stars. There’s El Garro de Tigre (Tiger’s Claw), El Pato de Parro (“Barefoot”), El Chapulín (Grasshopper), and El Chango (Monkey).

Every year in August, the Mexican national pelota mixteca championships are held in Bajos de Chila, Oaxaca, where all the best teams gather to face off in a countrywide tournament. The two top teams, Valles Centrales and Los Ahijados de Nochixtlán, Pacheco said, are “like the Dodgers and the Yankees.”

But as time passes, some of these legends of the game are getting older. Many of the stars of the ’80s and ’90s have retired, and in the past couple of years, Pacheco said, five close friends and former players have passed away, including Luis Ramirez Zarate last year.

The majority of active players today are in their thirties and forties, with a few guys left still playing well into their sixties, but there are a few newer players that are learning the ropes.

Team Without a Home

Each week on Thursday afternoon, the pelota mixteca team practices on a strip of dried-out grass tucked behind the baseball field at Santa Barbara High School. The section of field isn’t long enough to hold official games, and the uneven grass often sends the ball shooting in unpredictable directions, but it’s all they have for now.

When the group started playing in town more than 20 years ago, they gathered at the track at Carpinteria High School’s football stadium, which had a perfect strip of dirt, but when the stadium underwent a

renovation, the team was sent looking for another suitable option.

For a while, they played in Isla Vista, at Tucker’s Grove, near Los Carneros, or anywhere they could find a dry strip of land with enough space for them.

“We would like to have our own space,” Pacheco said. “It would be good if we had the space to play even just one game, just one tournament.”

Since the sport made its way to the U.S. over the past three decades, teams have popped up all across the state in Fresno, Gilroy, Oxnard, San Diego, San Bernardino, San Fernando, and Santa Cruz. These teams all compete together, along with other teams from Texas and Mexico.

But of all the cities with organized pelota mixteca teams, Santa Barbara is one of the few that does not have a designated field where they can play or host other teams.

Pacheco has been working to try and get a place in the city, but so far it has been an uphill battle to find a patch of open space in a city where every parcel is prime real estate.

After working with the folks at Casa de la Raza, Pacheco got in touch with City Councilmember Oscar Gutierrez, who has been helping with the search.

So far, Gutierrez said it seems that any space is hard to come by in the city — even if it’s just a 300-foot stretch of dirt. He’s asked the city’s Parks and Recreation Department: “They said they don’t really have a spot,” he said. He asked Santa Barbara Unified School District but was met with another “no.”

“It’s just hard trying to find a spot,” Gutierrez said. “I’ve been racking my brain, even just driving around town looking for spaces that might work. Trying to find a space with 300 feet of dirt is hard in Santa Barbara.”

He’s started exploring outside city limits, asking Santa Barbara County Supervisor Das Williams and Goleta City Councilmember James Kyriaco if they could try to find any space for the team to play.

“I think it’s really special to be able to have this sport here, since it’s so rare and ancient,” Gutierrez said.

¡Va de Buena!

From the ancient courtyards of Mesoamerica to the hidden mountains outside Oaxaca and then thousands of miles north to the California coast, the sport of pelota mixteca has proved its will to survive and adapt to new eras.

In the original days, dignitaries and warriors took to the court in battles for wealth and power. When the game was resurrected, it was played by Oaxacans proud to revive long-buried traditions. Its newest players are the working-class immigrants, surviving in a new country and keeping alive the customs of their ancestors, decompressing after a week’s worth of hard work by smashing a rubber ball with their friends.

This core group of ballplayers of Santa Barbara — Pacheco, Genaro Cruz, Ramon Cruz, Esteban Castillo, Venancio Lopez, Julio Lopez, and Angel Lopez — or as they call themselves, Los Amigos Peloteros, are committed to keeping the tradition alive here and passing it along to their children, just as their parents did before them.

“We thank you for the spaces where we have been able to practice this sport, and we will continue knocking on doors to be able to obtain more spaces that allow us to continue with this game,” Pacheco said. “We remain united so that our sport does not die.”

Or, as the pelota mixteca saying goes: “Que salta el hule … va de buena!” (“Let the rubber bounce … it’s going well!”)

You must be logged in to post a comment.