Santa Barbara’s

Elsa Granados

Stands with Spain

to End Sexual Assault

STESA’s Longtime Executive Director

Helps Spanish Government Establish

52 Rape Crisis Centers

By Callie Fausey | June 22, 2023

When the Spanish government first contacted Elsa Granados in 2018, she had no idea she’d become instrumental in establishing a network of 52 rape crisis centers around the country.

Granados, the executive director of the nonprofit formerly known as the Santa Barbara Rape Crisis Center, didn’t even realize she was speaking to a high-level government official when the caller initially sought her advice.

She quickly discovered that Spain was embarking on a worldwide quest to find crisis centers to emulate as they established their own. The woman Granados was speaking to was not a counterpart, as she originally thought, but the personal advisor to the country’s Minister of Equality.

“[She said,] ‘Tell me more about your work, because we want to set up rape crisis centers here in Spain, but we don’t have any money,’ ” Granados said at a recent fundraiser on May 20. “So I said, ‘All good. In our country, we started our movement with no money. It was all volunteers — and there are some amazing things that one can do with volunteers and no money.’ ”

Rape Crisis Center Rebrand

That fateful call from Spain was five years ago, around the same time the Rape Crisis Center became Standing Together to End Sexual Assault (STESA). Started in 1974 out of a garage equipped only with a handful of telephones and volunteers, the Rape Crisis Center was Santa Barbara’s first-ever crisis hotline for sexual assault survivors.

According to STESA’s site, the rebrand was in response to community feedback that not all sexual assault necessarily means rape, to reflect the full scope of their many different services, and to show that the organization is more than a crisis center; it’s an “agent of community change.” After helping thousands of survivors and their loved ones in a multiplicity of ways, it truly is.

But it was also because the local nonprofit had difficulty finding an office space to rent in town. It’s bad for business, some said, or it makes people uncomfortable. In other words, you can’t build a McDonald’s next door to a rape crisis center.

Santa Barbarans live in such a beautiful place, others have surmised, that surely such an ugly thing as rape can’t be happening in our backyards.

“So we say, ‘Yes, it does,’ ” Granados said. “There’s still a great number of people on the South Coast that are not aware of our services, and they’re not aware of us.”

It may be an uncomfortable thought to fathom, but it’s true — sexual assault happens in this small community just as it happens everywhere else in the world.

Model of Empowerment

When contacted by Spain, Granados eagerly offered her assistance. The Spaniards had been searching for crisis centers in regions that shared their progressive values and found STESA’s intersectional empowerment model — which guides clients to heal on their own terms — appealing. After learning about STESA online, the minister’s advisor was impressed by the way they presented their support services. The Ministry of Equality sought to implement a similar empowerment model in its own centers nationwide.

In an interview with the Indy, Granados explained that STESA’s empowerment model differs greatly from the “medical model,” which treats survivors as if they have an illness. “As in, something is wrong with someone in the aftermath of an assault, so they need medication; they might be depressed,” she said.

“Given the status that doctors are given in our country, I think there’s this sense that the doctor knows best,” she continued. “In the empowerment model that we use, we don’t feel as though we know best.”

Granados gave the example of exploring reporting options with survivors. She said that often their staff is asked what they would do if they were in the survivor’s place.

“We always respond with, ‘We’re not in your place,’ ” she said. “Only you can make this decision. Only you know how it will impact your life.

“So it’s not for us to weigh in on — we can give you information, we can help you process, we can help you with support, but ultimately, the decision is yours.”

Sexual assault can often take away a person’s sense that they are in charge of their own life, so STESA works to “remind them that they have an internal strength and control,” Granados said.

‘We have to give attention to prevention. Otherwise, we’re going to be running hotlines for the

rest of our lives.’

—Elsa Granados, STESA’s executive director

Crisis in Spain

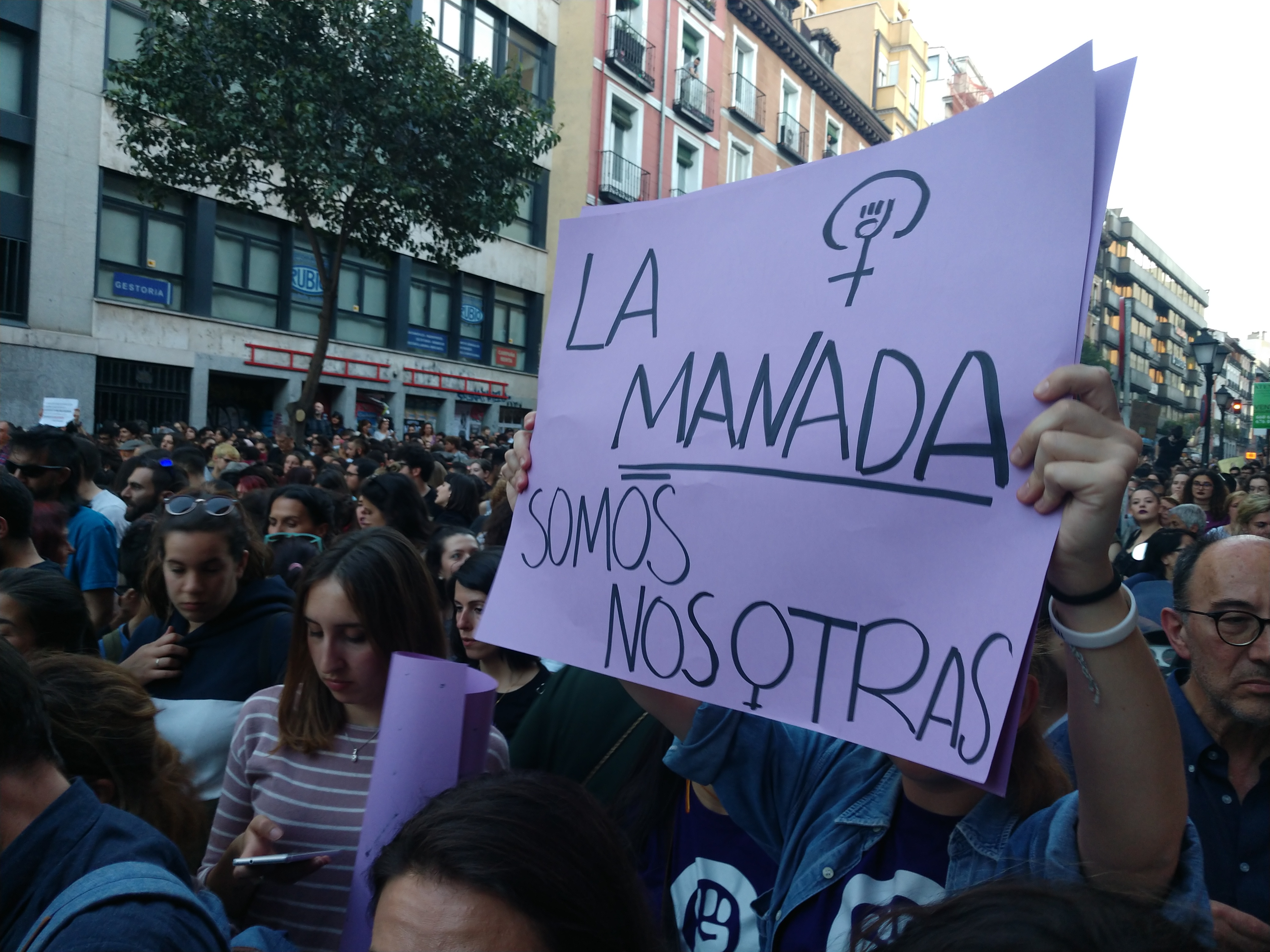

What helped catalyze Spain’s efforts was the notorious 2016 “La Manada,” or “wolf pack,” case, in which an 18-year-old woman was gang-raped on video by five men during that year’s bull-running festival in Pamplona. The courts initially acquitted the men of rape — instead sentencing them to only nine years for “sexual abuse” — but later increased their sentences to 15 years in 2019 following public outrage. It was one of the first cases to ignite a nationwide outcry for sexual violence legislation reform in Spain, and, a couple of years later, led to a new law making explicit consent the determining factor in sexual assault cases and providing funding and support for the country’s creation of crisis centers nationwide.

In September 2019, Spain established its first rape crisis center in Madrid. It was equipped to provide 24-hour, multilingual assistance to anyone who dialed the helpline from anywhere in the country — where one in every two women has experienced some form of sexual violence, according to a 2019 government survey.

In the United States, by comparison, one in four women (and more than two in five women of color) and one in six men have experienced sexual assault in their lifetime. In Santa Barbara County, there were 37 reported rape cases in 2022, but that is likely just a fraction of the actual number due to underreporting.

“The fact that the majority of women do not ask for help from any type of service or do not report should challenge us as a society and as institutions,” said Irene Montero, Spain’s Minister of Equality, in the summary of the 2019 survey.

A few years after Spain first reached out to Granados, on April 6, 2021, Spain’s Council of Ministers agreed to distribute $66 million euros from the European Union to set up 52 “24-hour Comprehensive Care Centers” for victims of sexual violence, with at least one in each of the country’s provinces and autonomous cities. They set a goal for the nationwide network of centers to be operational by 2023.

Victoria Rosell, Spain’s government delegate against gender violence, expressed in April 2021 that she was confident in the participation of all 17 autonomous governments in the specialized program, “despite the multiple

ideological discrepancies that may exist” between them.

When the Minister of Equality’s advisor once again contacted Granados that year, Granados told her that it was wonderful news.

“She says, ‘No, it’s not good. The way the money came in means we only have two years to spend it to set up 52 rape crisis centers,’ ” Granados shared at the STESA fundraiser.

But Granados, who has been the executive director of STESA for more than 25 years, told her, “Okay, roll up your sleeves. We’re not giving that money back. I’ve never given any money back — we’re not going to do it this time.”

Better Together

During that time, at the height of the pandemic, STESA had actually seen a decline in requests for their services as clients prioritized job security, childcare, and just daily survival in the new normal. “So our clients called us, but they didn’t want to talk about their sexual assault,” Granados told the Indy.

Instead, clients sought assistance with other pressing needs such as employment, education, food, and housing, and STESA adapted by providing them any information they needed. Only after addressing these concerns did clients feel ready to talk about their assault.

Virtual meetings became crucial for STESA, including educational programs for high school and junior high students. Through Zoom’s direct-messaging feature, students reached out to STESA educators, sharing similar experiences and seeking guidance on how to end their ordeal.

In that way, the virtual world opened a window for STESA’s educators to connect vulnerable students with the resources they needed. Similarly, virtual meetings facilitated communication between Granados and Spanish officials at a time when travel was restricted.

Granados, along with other panelists from Scotland and Canada, delivered Zoom presentations to offer support and guidance on center development. Emphasizing the importance of prevention alongside intervention, Granados highlighted STESA’s model and services, sharing insights on the nuts and bolts of establishing a crisis center.

“We have to give attention to prevention,” she told the Indy. “Otherwise, we’re going to be running hotlines for the rest of our lives.”

The Ministry of Equality then embarked on establishing the network, providing guidance and funding to autonomous communities like the Basque Country, which received $3.5 million euros between 2021 and 2022 to open centers in each of its provincial councils.

Fast-forward to the final months of 2022, and Granados was invited by the Ministry to present at an in-person international conference in Spain.

“You know, initially, I thought it was going to be only activists in Spain,” Granados said. “But it turned out that it was women from all over the world — India, Africa, Latin America, Europe.”

At the conference attended by more than 3,000 women from around the globe, Granados shared STESA’s experiences. She stressed the importance of adapting approaches to each culture and society while emphasizing universal elements such as believing survivors, validating their feelings, and providing comprehensive support.

“Ending sexual assault is highly dependent on changing cultural norms, societal norms,” she said. “Something that works in Santa Barbara may not work in Spain. … But the empowerment model, I feel, is universal.”

Although all 52 proposed centers have yet to be completed, this March the country reaffirmed its commitment to the project by approving the territorial distribution of $17 million euros among the communities still in need of a center. Granados said she’s continued to keep up with them and answer any inquiries that arise along the way.

“We’re having an impact beyond Santa Barbara,” she said. “And this isn’t Elsa; this is STESA.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.