Woman, Uninterrupted

It felt utterly right and good to kick off the celebrity tribute portion of this year’s SBIFF program to Angelina Jolie, who graced the Arlington with intelligence, minimalist poise, and grace last night. No, she is not among the Oscar nominated of the tribute subjects headed to the Arlington during the festival — Timothée Chalamet, Ralph Fiennes, Colman Domingo, Adrian Brody, Mikey Madison (and late-breaking addition to the festival Q&A list Demi Moore). But Oscar can be fickle and a shameless snubber, as we know. Jolie’s heroic performance as mega-diva Maria Callas in Maria was clearly award-worthy.

Jolie has passed this way before, appearing in a Q&A after a screening of her wonderful film (as director) First They Killed My Father, about the Cambodian atrocities under Pol Pot, at the Riviera Theatre in 2017. On Wednesday night, she settled in with veteran critic Leonard Maltin for the Modern Master Award proceedings, touching on her brilliant life as an actress, director, an ever-active activist, mother to many, and enduring subject of the slings and arrows of outrageous tabloid harassment.

She spoke of her turbulent youth, as the daughter of Jon Voight raised in lean circumstances by her single mother (who she gave her first Oscar and repeatedly paid homage to from the stage). “I was really dark,” she said, “and I think a lot of people related to my work because of that. The darkest moment was when I became famous … celebrity is a silly thing.”

She talked about the uncertainty of accepting the invitation of Maria director Pablo Larraín, but realizing, “I wanted to honor her life. I wanted to defend her.”

But the most powerful statement made on this night came at the very tail end, in her acceptance speech. After expressing compassion for Los Angeles wildfire victims and appreciation for first responders, she cast a broader light on the unfolding nightmare in American politics, articulating that “we can’t seek to impose systems at the expense of humanity.” In a sentence, she spoke eloquent truth to power gone mad.

We are the Worldlier

As SBIFF head and friendly spokesperson Roger Durling exclaimed in his opening night introduction at the Arlington Theatre, one of his goals has been to lean into the international aspect of the film festival. Programming director Claudia Puig is very much on the same page, and this year’s invitingly global and generally anti-xenophobic slate of films bears out the mandate.

International cinema is alive and well at the film center and Riviera for the next 10 days. And the fest-going crowds approve, as evidenced by an almost full house for the first screening of the festival — at 8 a.m., no less — the Sámi film My Father’s Daughter. Egil Pedersen’s inventive twist on the coming-of-age genre is a thoroughly ripe and entertaining treat, made all the more intriguing to us “southerners,” granted a glimpse of village life in the extreme north of Norway.

But this is no rustic/rural saga. Our identity-seeking 15-year-old protagonist, Elvira (the excellent young actress Sarah Olaussen Eira), is caught in a swirl of social media petty wars, provincial squabbles, and a domestic netherworld between her late-arriving father and lesbian mother. Early in the film, Elvira plays into imagined Danish roots, claiming, “I identify as a Dane.” Later, before the dust has settled, she tells her father “it turns out I’m genetically a half idiot.”

Humor is tucked into the folds of adolescent angst, including playful jabs at stereotyping, gibes about “Arctic thinking” and a reporter’s patronizing declaration that “Sámi people are always pleasant and gentle.” Thumbs up for this Arctic thinking person’s coming-of-ager.

A small pack of us “Breakfast Club” viewers raced over to try to catch the Peruvian film Mistura next, but were greeted by a firm but gentle “all sold out” warning by a kindly volunteer. The news was sad on one front, but a vital sign of festival health in the larger scheme.

Meanwhile, up at the Riviera Theatre (which has been thankfully anointed as one of the festival screening sites for the first time), the globetrot factor continued with the captivating film The Wolves Come Out at Night, a docufiction saga about an actual agrarian Mongolian family forced to go urban due to climate change conditions. This basic synopsis, however true and valid, doesn’t begin to convey the cinematic experience of being there, in the slow, unhurried pace and place.

Rustic rurality is in the bones of this sweet goat herder family in the spotlight here, forced by intensifying windstorms and “desertification” in the Gobi region of Mongolia to move to the outskirts of the city of Ulaanbaatar. There, waves of displacement anxieties and longing dreams of horses cloud the family bond. It’s a visually beautiful and bittersweet simple story with larger real-world ramifications.

Apparently, Wednesday was herding-based cinema day in town. But in the radically different and slicker film Shepherd, a Quebecois film shot in the mountainous regions of Provence and the French Alps, the harsh but also sometimes lyrical realities of the shepherd’s life mixes with a tail of idealistic youth in romantic philosophy. Mathyas (Félix-Antoine Duval) is an escapee from his modern life as a Montreal ad agency sloganeer, who opts to pursue the life of a sheepherder, to which skeptical herders reply “oh, you’re a back-to-nature pothead?”

Writer-director Sophie Deraspe’s warm and fuzzy but also gritty film, based on a semi-autobiographical book by Mathyas Lefebure, deals with the varied approaches to animal care — some violent, some nurturing, and the allure of finding romance and a true sense of “being” while tending sheep in a high alpine pasture. Who would have thought that shepherding Cinema could be so engaging?

A Cat’s Life, a Planet’s Life

And speaking of simple stories of global import, one of last year’s most surprising and captivating films was the now Oscar nominated animated film Flow, whose Latvian director Gints Zibalodis showed up as part of a star-studded animation panel at the Arlington yesterday afternoon. Also on the panel were Nick (Wallace and Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl) Park, Kelsey (Inside Out 2) Mann and Chris (The Wild Robot) Sanders, all Oscar-nominated artists. Flow garnered Oscar nods in both the Best Animation and International Film categories, as well it should.

The tale from a cat’s eye-view of a mysterious flood scenario forcing tolerance and cooperation between species —a clear metaphor for the current human condition — is a masterful and uniquely creative example of contemporary animation. Zilbalodis drew on a synthesis of visual stylization, his own co-written music and a seamless narrative “flow” with an accent on liquidity (as he explained, getting the cat’s signature kinetics correct was challenging, given the feline’s slinky and “almost liquid” body motions).

The unusual degree of filmic invention woven into this “family friendly” piece has partly to do with the director’s will to explore and improvise. “I’m not rigidly following the script,” he said. “It was very intuitive and organic. Every shot is unique.” He also integrated musical elements during the creative process, versus in a post-production manner. “Without dialogue,” he commented, “there is a gap that has to be filled with other elements — including the camera and the music.”

Closing out the panel discussion, Zilbalodis addressed moderator Durling’s question regarding the state of the art of animation and its future state. He noted “now that you can render reality so easily — I made Flow with free software (Blender) and on PCs — where else can you go? It is similar to the arrival of photography, which helped inspire painters to explore abstraction. It’s easier to sell a story based on realism, but when it’s more stylized and abstract, things get more interesting.”

Premier Events

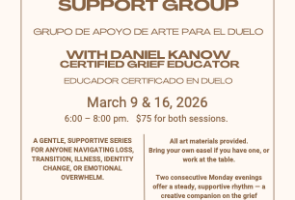

Mon, Mar 09

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

ART 4 GRIEF Support Group

Sat, Mar 14

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Red, White, & Blues II: The American Songbook

Sun, Mar 15

3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Red, White, & Blues II: The American Songbook

Thu, Mar 12

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Poetry, Typewriters, and Collage Workshop

Thu, Mar 12

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening of Wild Hope: PBS Film Screenings

Thu, Mar 12

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Lights Up! Presents: “The Addams Family”

Thu, Mar 12

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

UCSB Music of India Winter Concert

Fri, Mar 13

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

GLOW X: A High-Definition Neon Experience

Fri, Mar 13

7:00 PM

Goleta

Folk Orchestra of Santa Barbara Celtic Concert

Fri, Mar 13

7:00 PM

Goleta

Peace Event

Sat, Mar 14

1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

St. Patrick’s Day Irish Firedance

Sat, Mar 14

1:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

SBCC’s Science Discovery Day

Sat, Mar 14

3:00 PM

435 State St, Santa Barbara, CA 93101

☘️ Santa Barbara St Patrick’s Day Bar Crawl & Block Party

Mon, Mar 09 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

ART 4 GRIEF Support Group

Sat, Mar 14 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Red, White, & Blues II: The American Songbook

Sun, Mar 15 3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Red, White, & Blues II: The American Songbook

Thu, Mar 12 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Poetry, Typewriters, and Collage Workshop

Thu, Mar 12 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening of Wild Hope: PBS Film Screenings

Thu, Mar 12 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Lights Up! Presents: “The Addams Family”

Thu, Mar 12 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

UCSB Music of India Winter Concert

Fri, Mar 13 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

GLOW X: A High-Definition Neon Experience

Fri, Mar 13 7:00 PM

Goleta

Folk Orchestra of Santa Barbara Celtic Concert

Fri, Mar 13 7:00 PM

Goleta

Peace Event

Sat, Mar 14 1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

St. Patrick’s Day Irish Firedance

Sat, Mar 14 1:00 PM

SANTA BARBARA

SBCC’s Science Discovery Day

Sat, Mar 14 3:00 PM

435 State St, Santa Barbara, CA 93101

You must be logged in to post a comment.