Carpinteria’s longstanding urban-rural boundary has remained mostly untouched for four decades, creating a clear sense of where the city sprawl ended and the many acres of farmland just outside the city limits began. But over those four decades, the growing need for housing has slowly started to stretch the limits of these long-held boundaries.

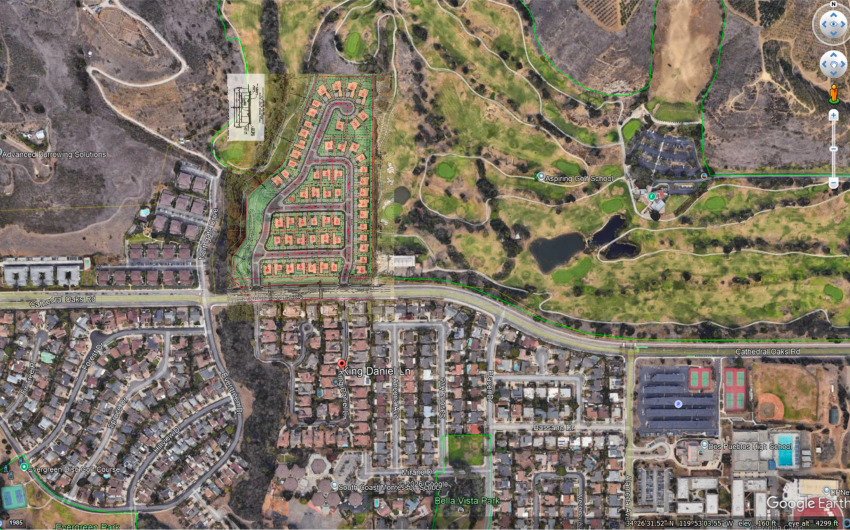

This battle was at the center of the California Coastal Commission’s recent decision regarding three parcels of land just outside of Carpinteria city limits — technically in Santa Barbara County territory — which the commission unanimously approved to be rezoned for high-density housing, despite a wave of opposition from Carpinteria city officials and residents at the November 6 hearing in Sacramento.

The Coastal Commission was considering the rezones of the three parcels following a request from the Santa Barbara County Planning and Development Department, as part of the county’s attempts to account for the state’s mandated quota of 5,664 units of housing in the unincorporated areas in the county over the next six years.

Santa Barbara County Planning and Development Director Lisa Plowman spoke at the hearing in Sacramento, saying that the county did not take the decision to rezone parcels lightly. She recounted the challenges the county faced with the state asking for a much higher number of units to address the growing housing shortage, and said the county “hasn’t built any meaningful housing in about 40 years.”

During the Housing Element planning cycle, the county looked at more than 1,000 potential rezone sites, in a lengthy process that included 11 public hearings and months of community outreach. At least 200 sites in the Carpinteria Valley were considered. Planners spoke to property owners to gauge interest, then narrowed down the sites, crossing out parcels that didn’t meet the criteria due to location, available utilities and services, construction feasibility, or one of more than a dozen layers of environmental constraints.

After all were screened, the county rezoned 18 privately owned sites, the bulk of which ended up being in the eastern Goleta Valley, where thousands of units are potentially in the pipeline.

When it became clear that the county would still need to rezone additional sites to meet the state’s target on the South Coast, the county considered nine county-owned sites, and started looking elsewhere for property owners who might consider housing developments. Only four privately owned sites met the criteria in the Coastal Zone: a vacant lot in Isla Vista owned by the Friendship Manor retirement community; two agricultural parcels outside Carpinteria owned by the Van Wingerden family; and a small farm on Bailard Avenue that was formerly owned by the school district.

The county’s decision to request a rezone of the three sites in the Carpinteria Valley, which all lie on the northern edge of city limits, sparked a strong response from city officials and slow-growth advocates who worried that the three developments — with a potential for 686 units of housing — would bring too much of an impact on the city’s resources.

The commission received more than a hundred letters prior to the meeting, and a petition to “Save the Bailard Farm” garnered nearly 2,500 signatures from concerned residents. Neighbors worried about traffic impacts, the loss of traditional agricultural land, and the infringement on the long-held buffer between farmland and high-density housing.

Among the vocal opposition was City Councilmember and third-generation Carpinteria resident Julia Mayer, who said she has watched the town’s “focused growth” over the years, guided by local government leaders who looked to protect “one of the last truly small beach towns on the California coast.”

Mayer and Carpinteria City Manager Michael Ramirez both traveled to Sacramento to plead with commissioners to refuse the rezones and preserve the city’s character. They worried that the decision could set an alarming precedent and open the door for speculation on neighboring properties, which developers have already been eying for housing development. “Once farmland is gone, it’s gone forever,” Mayer said.

Alex Van Wingerden, whose family has farmed in the Carpinteria Valley for half a century, said that the family’s agricultural business would always remain their “legacy and livelihood.” The decision to use two of the properties for housing was intended to address the dire need for farmworker housing, he said. Currently, 80 percent of the company’s employees commute to work daily from Ventura because there’s no affordable housing in Carpinteria.

Coastal Commission staff, county planners, and the property owners of the three parcels all worked together to craft two modifications that would ensure the developments would serve low-income workers. All three properties will need to have a minimum of 32 percent affordable housing — 12 percent higher than the state-mandated requirement — and all affordable units will remain deed-restricted for “the lifespan of the development,” instead of the usual 90-year term.

Coastal Commissioner Meagan Harmon was forced to recuse herself from the decision due to a possibility that she was involved in one of the early stages of negotiations in her capacity as an attorney. All remaining commissioners unanimously voted to go forward with the rezones, adding the two conditions calling for a higher percentage of affordable units and an indefinite term for affordability.

Councilmember Ray Jackson said he appreciated the input from the Carpinteria officials and residents, and that he “felt their pain” regarding the pressure from the state to build more housing. “I understand the passion of your residents,” Jackson said. “It’s hard — particularly when you’re a small beach community— and all of a sudden you’re being told by folks up in Sacramento that you need to be denser, that you need more housing.”

The Santa Barbara County Board of Supervisors will need to approve the amendment increasing the percentage of affordable housing to 32 percent for these three parcels. There is currently a proposal in the works for the Bailard site, with the County Housing Authority working with Red Tail LLC toward a 170-unit mixed income complex. There are no applications currently submitted for the Van Wingerden parcels, though the two sites are now zoned for up to 416 units.

Premier Events

Wed, Mar 04

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

IWC Study Circle and Discussion – March 2026

Mon, Mar 09

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

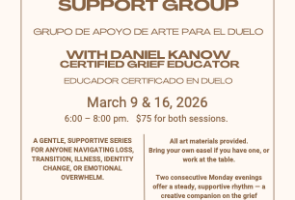

ART 4 GRIEF Support Group

Sat, Mar 14

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Red, White, & Blues II: The American Songbook

Sun, Mar 15

3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Red, White, & Blues II: The American Songbook

Thu, Mar 12

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Poetry, Typewriters, and Collage Workshop

Thu, Mar 12

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening of Wild Hope: PBS Film Screenings

Thu, Mar 12

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Lights Up! Presents: “The Addams Family”

Fri, Mar 13

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

GLOW X: A High-Definition Neon Experience

Fri, Mar 13

7:00 PM

Goleta

Peace Event

Sat, Mar 14

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

The Vada Draw

Sat, Mar 14

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Lights Up! Presents: “The Addams Family”

Sat, Mar 28

All day

Santa Barbara

Coffee Culture Fest

Wed, Mar 04 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

IWC Study Circle and Discussion – March 2026

Mon, Mar 09 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

ART 4 GRIEF Support Group

Sat, Mar 14 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Red, White, & Blues II: The American Songbook

Sun, Mar 15 3:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Red, White, & Blues II: The American Songbook

Thu, Mar 12 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Poetry, Typewriters, and Collage Workshop

Thu, Mar 12 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening of Wild Hope: PBS Film Screenings

Thu, Mar 12 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Lights Up! Presents: “The Addams Family”

Fri, Mar 13 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

GLOW X: A High-Definition Neon Experience

Fri, Mar 13 7:00 PM

Goleta

Peace Event

Sat, Mar 14 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

The Vada Draw

Sat, Mar 14 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Lights Up! Presents: “The Addams Family”

Sat, Mar 28 All day

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.