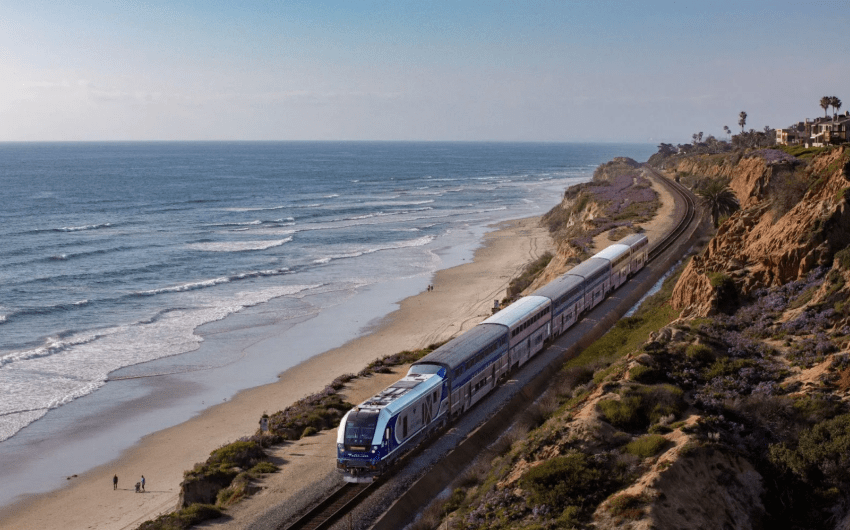

Stay up-to-date with all things film fest by subscribing to our Dispatches from SBIFF newsletter featuring

daily reports of what happened last night, and previews of what’s next at the

Santa Barbara International Film Festival. Subscribe here.

Santa Barbara Independent is a proud sponsor of SBIFF’s Audience Choice Award.

Don’t forget to vote for your favorite films.

Julian Schnabel has made several fine and innovative films in his time. In the Hand of Dante is not one of them. The film, which had its North American premiere at the festival, is an overlong and pretentious pastiche of mob-land-style violence and references to Dante’s The Divine Comedy, with sprinklings of Da Vinci Code tropes as a side dish.

The film is based on the book by Nick Tosches, who went to Italy and dove into Dante’s world to create a phantasmagorical head trip of a story, leaping from the 21st to the 14th century and back and between the historical Dante and a fictionalized version of Tosches himself. Oscar Isaac takes on the challenge of playing both writer roles. Schnabel’s time-tripping scheme is to set the more modern scenes in black and white and the Dante-era sections in living color.

With its surfeit of ultraviolence — beaucoup bullets to the forehead — it seems that Schnabel is trying to out-Scorsese Scorsese, who, ironically, appears as the sagacious Isaiah, spouting wisdom through his jumbo beard.

In a way, the film’s eclectic excesses circle back to the neo-expressionistic paintings that made Schnabel famous in the 1980s, in which a lot of ideas and objects were thrown at the canvas, with the hope that some of it would stick. And some of it does stick here, with select scenes, contrapuntal concepts and literary flights grabbing our attention, only to be diffused in the sensory deluge. We are reminded of some of the later, lesser Terrence Malick films, rambling affairs which have also graced SBIFF screens in the past. File under “nice tries.”

In a post-screening Q&A, Schnabel was in-house late Wednesday afternoon, fielding some questions from the audience. On the subject of the decision to film 2001 scenes in vintage-y black and white, with color going to the medieval scenery, Schnabel quipped, “Most people would have done the opposite way — good reason not to do it that way. When Dante was alive, the world was in color. If you look at what’s happening right now, it’s like a purgatory in black and white, what’s going on in this country and around the world.

“But what happens to art, sometimes it just becomes a commodity, and it has a value, monetary value. But that’s not what the substance of art is about. That’s not why Dante wrote, that’s why Nick went back there. He kind of went on that trip because it was his work.”

Asked if he went through a transformation in making this ambitious film, akin to the transformation of its two main characters, Schnabel answered in the affirmative. “Yes,” he said, “I went crazy. I went crazy because with the people that got involved in this, I don’t know if they’d ever seen my work before or knew what I was going to do. If they read the script, they would have known that it would be like this. There were definitely some people who said, ‘Can we make this? Can’t we chew people’s food for them a little bit and make this a bit more accessible?’

“No, people got it,” Schnabel continued. “Take the journey, go through it. And why would we want to chew somebody’s food for them? I mean, isn’t that your pleasure to do that? I like to make a movie where people can actually dig into it. It’s that kind of movie.”

Life on the Fringes, Justice Served

Whether by design or by programmatic calculation, two U.S. films this year deal charmingly with stories in which characters on the societal fringes battle forces of oppression and actually triumph through legal wins. The triumphant scuffler heroes are an unhoused woman’s long fight to regain her towed ’91 Camry in Stephanie Laing’s Tow — starring the irrepressibly fine actress Rose Byrne — and the gruff but loveable misfit in the Hamptons played by the great Tim Blake Nelson, in the aptly named On the End. Both are well worth a slot in the fest-goer’s itinerary.

I’m not an Academy votin’ man, but if I were, I would vote — and vote often — for Byrne as Best Actress for her superlative turn in If I Had Legs I Would Kick You. She is the prime attraction in Tow, bringing a true-life saga of a hapless Seattle woman’s fight for justice and for her Camry (her temporary vehicular abode). Her opening soliloquy, applying for a veterinary job, is worth the price of admission. Her tale of struggles strategically entails themes of the injustice of the class system and the plight of the homeless: A woman from her homeless shelter tells her, “You’re homeless, and that’s as bad as being Black or brown in this country.”

With this comic-dramatic performance, Byrne is up for the unofficial award for Best Actress of SBIFF 2026.

With On the End, writer-director Ari Selinger had us at Tim Blake Nelson — star of O Brother, Where Art Thou? and other Coen Brothers films, and director of Eye of God and other tasty indie films. Here, he shines, roughly, as a gruff frump decamped in the less toney end of the Hamptons, in Montauk, based loosely on a true story. He is also in love with a fellow diabetic nicknamed “Freckles” (Mereille Enos, creating an unpretentiously magnetic, ceremony-shucking personality in the role).

His ramshackle house and auto repair yard are being threatened by the rapacious law of the gentrification monster (something Santa Barbara knows about). But his pride and Freckles’s savvy combine to fight the development villains, right up the court system. It adds up to a funky love story on the outskirts, with justice in the offing.

Poor Napoleon, on the Farm

In the excellent and wickedly satirical Mexican film Versailles, a lost election leads a self-delusionary presidential candidate to extreme and unethical behavior. No, the film is not a Trump biopic in disguise, or not exactly. Director Andrés Clariond, a popular political columnist in Mexico, has created a baroque satire with echoes of Luis Buñuel and Paolo Sorrentino in its recipe.

Starring Cuauhtli Jiménez and Maggie Civantos as a conniving hacienda-owning couple, the film follows the handsome villain/protagonist’s response to his larger political loss by treating his plantation and population of workers as a fiefdom to be subjugated and exploited. The narrative goes over the top, as Napoleonic manners slip into the picture and a lavish faux-rococo party where workers are costumed and told to “be more European.” No, this is not based on a true story — at least not directly.

Last Wording

Schnabel: “If you see a Caravaggio painting, he painted it 700 years ago, something like that. But you walk up to the painting, and it brings you into its present. And that’s what happens. And that’s what art is. You can transgress death, you can have the same experience that somebody had 700 years ago. Looking at that painting, I think it works in the reverse. Also, maybe as you do that, you bring these people back to life.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.