Two miles off the coast of Goleta, Platform Holly rises from the Pacific. A 100-foot-tall steel industrial spire against the horizon, lit up like a modern constellation. Installed in 1966, Holly pumped oil for nearly five decades. Since closing in 2015 after the Refugio Oil Spill, the rig has stood idle — a relic of California’s petroleum past.

But beneath the water, the view changes entirely.

Divers descending along Holly’s legs encounter dense colonies of mussels, anemones, barnacles, and sea stars. Rockfish hover in the shadows. Lingcod patrol the lower crossbeams. The rig’s submerged jacket structure functions, in ecological terms, as a vertical reef.

“Platforms act as nursery grounds for some species of fish,” said Dr. Milton Love, a research biologist at UC Santa Barbara who has studied offshore platforms for more than 40 years. “Where are most of these baby fish? They’re not in the top part of the platform. They’re further down. They’re 80, 90, 120, 150 feet down.”

Now California must decide whether that reef remains.

On January 26, 2026, the California State Lands Commission released a Notice of Preparation for an Environmental Impact Report on the Platform Holly Decommissioning Project. Public scoping meetings are scheduled for February 19 at Goleta City Hall. Written comments are due February 23.

The proposed project identifies full removal of the structure as the primary course of action. Partial removal — cutting the platform at least 85 feet below the surface and leaving the lower portion in place — remains under consideration.

The distinction is not cosmetic. It goes to the heart of a long-running debate over what decommissioning should mean: restoration to pre-industrial conditions or preservation of an ecosystem that formed around industrial infrastructure.

Love’s research has documented unusually high densities of certain species on offshore platforms. In a 2000 study, he and colleagues reported that Platform Gail harbored adult bocaccio at densities an order of magnitude greater than those observed on dozens of comparable natural reefs.

But Love draws a careful line between local abundance and regional impact.

The University of California’s Select Scientific Advisory Committee on Decommissioning, in a 2000 report to the UC Marine Council, concluded there was “not any sound scientific evidence” that offshore platforms enhance or reduce regional stocks of marine species. The 27 platforms off California represent a small fraction of available hard substrate in the Southern California Bight, the report noted, and their contribution to overall reef habitat is limited.

Regional population effects, the committee found, cannot be predicted with reasonable scientific certainty.

While the committee cautioned against overstating regional benefits, its findings did not suggest the platforms are biologically inert. Removal would eliminate the dense sea-life assemblages now attached to the steel even if the broader population consequences remain uncertain.

For scientists like Love, that distinction matters.

From a fisheries standpoint, Love’s team examined what would happen if the top 80 feet were removed — the depth generally required by the Coast Guard for navigation safety. Using comparable reefs and shipwrecks as surrogates, they found that nursery function for most species persisted below that threshold.

“Cutting 80 feet below the surface,” he said, “most of the ecological services, as far as fish are concerned, remain intact.”

But the debate does not hinge solely on fish.

Linda Krop, chief counsel for the Santa Barbara–based Environmental Defense Center, argues that full removal is essential.

“We support the proposed project,” Krop said of the State Lands Commission’s identification of complete removal as the preferred option. “Because that involves not only removing the platform structure, but cleaning up the debris.”

Krop points to the removal of four Chevron platforms off Summerland in the 1990s. There, large “shell mounds” — accumulations of mussel shells, drilling muds, and cuttings — were left on the seafloor.

A 2000 environmental review by the California State Lands Commission found elevated concentrations of heavy metals and petroleum-derived compounds, including polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons, which are known to persist in sediments and can be toxic to marine life.

“People don’t realize what’s left behind,” Krop said. “It’s not just the platform structure. It’s drilling muds and cuttings: highly toxic.”

That same review found the biological value of the shell mound habitat to be “relatively low” and concluded removal would not eliminate significant or unique biological resources. However, dredging and removal risks stirring up contaminated material into the water column, which degrades water quality in the short term.

A 2023 Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement prepared for the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement evaluated offshore decommissioning across Southern California. It concluded that complete removal would cause greater seafloor disturbance and permanent loss of rig-based habitat than partial removal alternatives, though most impacts could be mitigated to negligible or minor levels.

The federal review did not assume platforms confer regional ecological benefits.

Platform Holly sits in state waters, a distinction that matters. After operator Venoco declared bankruptcy in 2017, the State Lands Commission seized the site under its police powers. ExxonMobil, which previously held the lease, remains financially responsible for most of the decommissioning costs.

California’s 2010 Marine Resources Legacy Act allows partial removal of offshore platforms under a “rigs-to-reefs” framework. No platform in state waters has been converted under that program.

The law was designed to be initiated by oil companies. In Holly’s case, the state owns the structure outright, placing regulators in the unusual position of determining its fate directly.

The question is not whether Holly comes down. It is whether restoration means returning the seafloor to mud — its pre-1966 condition — or preserving a 60-year-old artificial reef that has become embedded in the marine ecosystem.

Late in separate interviews, both Love and Krop were asked the same question: If you walked along the bluffs tomorrow and looked out at the horizon — and Platform Holly was gone — how would you feel?

Love paused before answering.

“As a citizen,” he said, “I view the wholesale slaughter of any group of animals — I just don’t believe in that. And basically, you’re saying, we’re gonna kill all these mussels and sea stars and anemones because of a bad career move on their part. They landed on a piece of steel instead of a rock.”

He emphasized that his personal views do not guide his scientific work.

“But that’s me speaking as a citizen,” he added. “My own philosophy doesn’t color my research.”

Krop’s answer was assured.

“Grateful,” she said. “And at peace.”

For her, removal is not destruction but restoration — the fulfillment of a long-standing legal and environmental obligation.

“When these platforms were installed,” she said earlier in the interview, “they were installed with the condition that, when operations were done, everything could be removed and the marine environment would be restored to its natural condition.”

Between those two reactions lies the philosophical divide now before state regulators.

The Environmental Impact Report process will extend through public scoping, draft analysis, public comment and final certification. State regulators must weigh ecological uncertainty, contamination risks, navigational safety, cost, and public sentiment.

The public will have its say on February 19.

Premier Events

Fri, Mar 06

2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Music & Meditation SB – Concert March 6, 2026

Sat, Mar 07

9:00 AM

Carpinteria

El Carro Park Cannabis Career Fair – Carpinteria

Sat, Mar 07

2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Autobiography of a Yogi, the Legacy of Yogananda

Sun, Mar 08

6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

6th Eco Hero Award Brock Dolman & Kate Lundquist

Mon, Mar 09

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

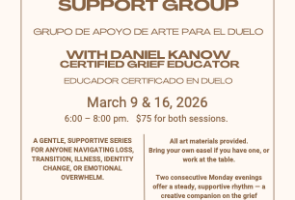

ART 4 GRIEF Support Group

Fri, Mar 06

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening with Steep Canyon Rangers

Fri, Mar 06

8:00 PM

Santa Ynez

Funk Band Kool & The Gang at Chumash

Sat, Mar 07

12:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Spring 2026 Healing Arts Faire

Sat, Mar 07

7:00 PM

Carpinteria

The Magic’s In the Music

Sat, Mar 07

7:30 PM

Goleta

UCSB Arts & Lectures Presents Arturo Sandoval Legacy Quintet

Sat, Mar 07

7:30 PM

Goleta

Jazz Concert with Wayne Bergeron

Sun, Mar 08

10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Fairytale Weekend at the Zoo

Sun, Mar 08

1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SB Craftivists “Resist with Love KNOT Hate Knit-In

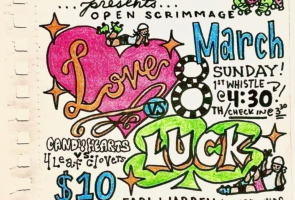

Sun, Mar 08

4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Brawlin’ Betties: Love v. Luck Scrimmage

Sun, Mar 08

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

SBAcoustic Presents Natalie Gelman & Mark Legget

Fri, Mar 06 2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Music & Meditation SB – Concert March 6, 2026

Sat, Mar 07 9:00 AM

Carpinteria

El Carro Park Cannabis Career Fair – Carpinteria

Sat, Mar 07 2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Autobiography of a Yogi, the Legacy of Yogananda

Sun, Mar 08 6:30 PM

Santa Barbara

6th Eco Hero Award Brock Dolman & Kate Lundquist

Mon, Mar 09 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

ART 4 GRIEF Support Group

Fri, Mar 06 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

An Evening with Steep Canyon Rangers

Fri, Mar 06 8:00 PM

Santa Ynez

Funk Band Kool & The Gang at Chumash

Sat, Mar 07 12:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Spring 2026 Healing Arts Faire

Sat, Mar 07 7:00 PM

Carpinteria

The Magic’s In the Music

Sat, Mar 07 7:30 PM

Goleta

UCSB Arts & Lectures Presents Arturo Sandoval Legacy Quintet

Sat, Mar 07 7:30 PM

Goleta

Jazz Concert with Wayne Bergeron

Sun, Mar 08 10:00 AM

Santa Barbara

Fairytale Weekend at the Zoo

Sun, Mar 08 1:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SB Craftivists “Resist with Love KNOT Hate Knit-In

Sun, Mar 08 4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Brawlin’ Betties: Love v. Luck Scrimmage

Sun, Mar 08 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

You must be logged in to post a comment.