The ocean shapes Santa Barbara. She shapes the land, the lifestyle, the people. Some have learned to harness her power— to sync with a band of energy that started thousands of miles away.

And this small stretch of coastline between the channel and the mountains, with some of the best waves in the world, has produced names that have shaped surfing globally. Not just riders, but also innovators, for a surfer is nothing without their board.

This is the town where Greenough pushed the envelope. Where Yater glassed at night and surfed at dawn. Where Merrick built boards for an elite team that shaped a generation.

“Santa Barbara is very unique,” said Marc Andreini, a lifelong shaper and surfer. “The coastline faces southeast and the waves come from the northwest, so they wrap all the way into the Channel and around the point — like cracking a whip.”

Here in Santa Barbara, our pipeline is Rincon. Queen of the Coast. “The waves may look small and clean, but they take a lot of skill and trim speed,” said Andreini. “That’s why our boards ride high and fast. All the energy’s at the top of the wave.”

Waves like the ones at Rincon, Leadbetter, Hammonds, and El Capitán created a need for boards that could move with the wave’s long, drawn-out lines. Boards that could hold speed through a continuous wall of falling water.

In the late ’50s, a man named Reynolds Yater, better known as “Renny,” came to Santa Barbara to catch lobster. In the off-season, he was shaping boards. After the movie Gidget premiered, surfing became all the rage, and Renny began to flood the Central Coast market with surfboards.

Yater boards were (and are to this day) typically longboards, with his iconic “Spoon” nose, meaning the top third of the board is a down-step to increase maneuverability. But these boards would not be the only iconic and innovative slabs of wood to come out of S.B. Enter Greenough.

In the 1960s, Santa Barbara native George Greenough was riding something totally different — a flexible-finned kneeboard that moved in ways no longboard could. He wasn’t just trimming across waves — he was snapping off the lip, going vertical, carving lines that were almost futuristic. So, what did surfers do? Start cutting their longboards in half. Overnight.

“Yater is one of the original shapers of California. George Greenough grew up here and is credited for sparking the shortboard revolution, which has changed surfing globally,” Grayson Nance, co-owner of Surf N’ Wear’s Beach House, told me. “They have had such a big influence on surfing in general, and for both of them to have lived in this same small town is amazing.”

Yater and Greenough weren’t just surfers — they were builders. Lobstermen, fishermen, guys who worked with their hands. Both obsessed with function. Both obsessed with what a board could do. They were influenced by the sea and the boats on it. Hull shapes, flow, resistance, glide — all of that translated from the docks to the shaping bay.

“You had this mix of people who worked on boats and surfed,” said Cooper Boneck of Mesa Surfboards. “You can really see where those two worlds blended. People figuring out what they wanted the bottoms of boards to do — that came from boat design.”

These early Santa Barbara shapers weren’t thinking about the “surf industry.” They weren’t trying to scale. They were experimenting. Figuring out how to ride the best waves and have the most fun. And it wasn’t just Yater and Greenough. There was a crew of pioneers: Bob McTavish, Tom Roland, Brian Bradley, Tom Hale, John Thurston, John “Ike” Eichert, Rich Reed, and many more.

“In a way,” said Wayne Lynch, Australian surfer/shaper in the documentary Spoons: A Santa Barbara Story, “we were like astronauts building our own little spaceships and going off out into space, and discovering all these new places and planets and coming back down and meeting up and talking about it.”

This was no solo effort. It was a scene. A tribe. A tight-knit group of shapers, tinkerers, and seamen building off each other’s ideas in garages and backyards. The effect: A quiet surf town had helped start a global movement.

Before the logos, before the pro tour — there were guys like Marc Andreini, Jeff White, and Renny Yater, shaping out of garages, working-class sheds, and backyards.

Marc Andreini moved to Santa Barbara in 1957, at age 6. He and his brother were raised by a single mom who learned how to surf with the Beach Boys in Hawai‘i. Embedding that passion in her sons, the boys grew up surfing Ledbetter, Miramar, and Hammonds, on boards that were heavier than they were.

Soon the time came, as it always does, when a board needs a patch job. Andreini was scrappy — in his teens, he started repairing boards with house paint and spackle. Soon, he got to level up his craft, as he was one of the original “shop groms” at White Owl Surfboards, which opened in 1961 in Summerland.

The owner, Jeff White, didn’t shape himself — he glassed the boards, ran the business, and made something more valuable than a product. He made a place. “He took in the wayward kids — the ones without dads,” Andreini said. “He didn’t just put us on boards. He gave us something to belong to.”

That sense of local mentorship defined the era to the point that Andreini has been the shaper for White Owl boards for decades.

White soon moved the shop to 209 West Carrillo Street in 1965 and renamed it Surf N’ Wear. It became the first true retail surf shop in Santa Barbara — they sold boards, sandals, and tees. White formed a small surf team of the kids who worked and hung out there, and a community was built.

In the’ 60s, Yater and a tight group of surfers formed the Santa Barbara Surf Club — not just for camaraderie, but for access. Specifically: Hollister Ranch.

If you’re from around here, you know the deal. Hollister Ranch is still, to this day, a gated stretch of pristine coastline. Beautiful rolling sets, empty points. And completely off-limits to the public.

But back then, if you were in the club and you played by the rules, you could surf it.

“The surfers were basically bodyguards,” Nance explained. “You had to live in Santa Barbara County to even be considered. No guests, no outsiders. The club gave you access, but you had to protect that access.”

The original bylaws of the Santa Barbara Surf Club spelled it out: “The purpose of this organization is to provide a special restricted surfing area within Santa Barbara County for its members … devoted to the enjoyment of surfing….”

Membership was capped at 80. No guests, unless it was your girlfriend (and she couldn’t surf). If you were lucky enough to get in, you surfed one of the best coastlines in California — in total secrecy.

Now enter the ’70s. If you grew up surfing in Santa Barbara — especially if you were a kid in the ’80s or ’90s — you probably rode a Channel Islands board.

Founded by Al Merrick, Channel Islands Surfboards started in a small shop on Anacapa Street. Merrick wasn’t just a good shaper; he was a team builder, making boards designed for youth. He worked with the next generation of Santa Barbarans on waves, including world champions such as Tom Curren and Kim Mearig. Eventually, most of the world tour was riding CI shapes.

Outside of trophies and championships, the Santa Barbara surf soul is more about having fun on the waves and doing it with your buddies. “I just want to go surfing. I love making boards, but I’d be happy just making them for myself.” Andreini told me, looking up at his 10′8″ Glider.

And this love is passed down; not only in the way Gayle DeFresne did for her son Marc Andreini, but also shapers passing down the craft.

Grayson Nance grew up with all of it. His dad, Roger, started collecting boards back in 1975 — long before “vintage” meant anything. He just saw something worth saving.

“My dad came down to go to UCSB in the ’70s,” Nance said. “I was born and raised here. Grew up surfing. I’ve always been in the surf shop since I was a kid.”

What surf shop, you may ask? White’s Surf N’ Wear shop. When Rodger Nance came in in the ’70s, he partnered with White and joined the White Owl family. There, boards hang from the ceiling like stained glass. Renny Yater stops by frequently. Stories spilled out constantly.

Nance represents a kind of modern collector — not just of boards, but of history. Of names, lineage, ritual. The idea that surfing is cultural stewardship is what links him to others in his generation. Like Cooper Boneck.

Boneck grew up on the Mesa. Learned to surf at Leadbetter. His tenth birthday was at Rincon. His first glimpse into board design came from the shaping bay of a neighborhood dad, John Tustin, of Tustin Surfboards.

“He would glass boards at the house,” Boneck said. “We’d just smell the resin — we thought he was the coolest guy alive.”

Fast-forward a decade. Boneck is now shaping Mesa Surfboards, pulling from Santa Barbara’s high-performance roots (CI boards) with a retro flair. He is also slowly stepping into a more formal lineage — that of White Owl under Andreini. “I told Cooper, ‘You’re in,’” Nance said. “‘You’re part of the 20-, 30-year plan.’”

Boneck’s now working alongside Andreini — authentically hand-shaping boards. A difficult task to learn.

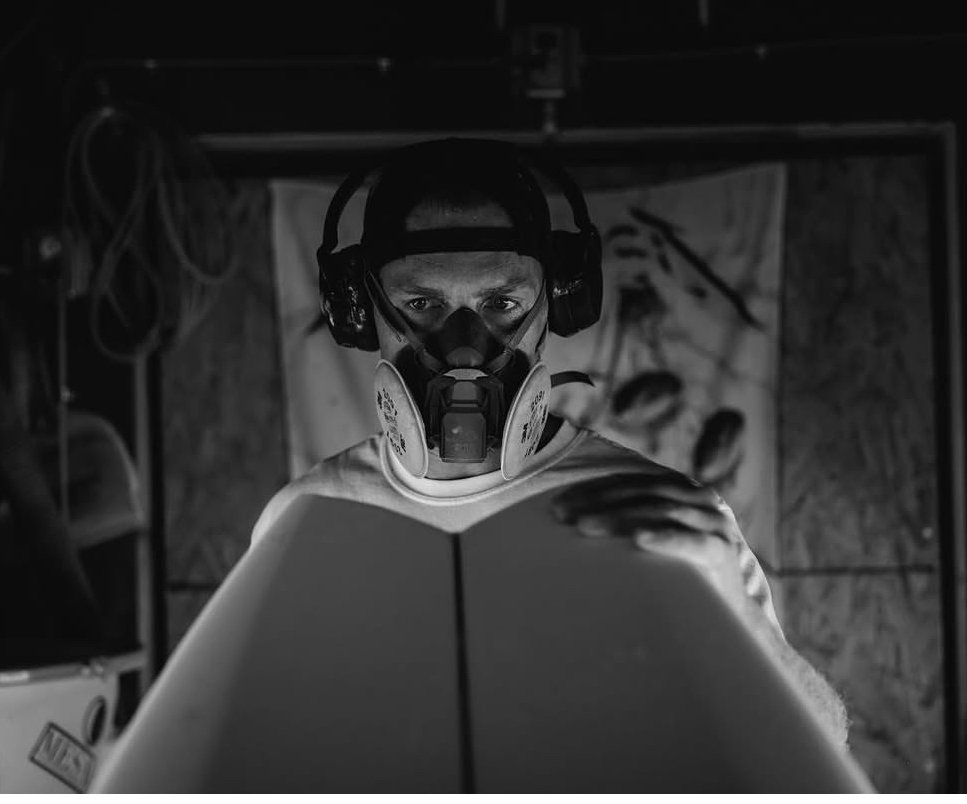

Cooper Boneck in the shaping bay, hand shaping his handmade Mesa boards | Credit: Courtesy of Cooper Boneck.

“What’s hard is knowing why you’re shaping a board a certain way; that is a complete unknown. You have to understand exactly every single angle of the design, what it’s doing, and how to blend it with all the other ingredients of that design,” Andreini said. “It’s a lifetime endeavor to accomplish.”

“I’m just trying to make good boards,” Boneck echoed. “And be part of the story.”

The story of the ocean and her riders. Generations of Santa Barbarans are out there to have fun — on tools they’ve shaped over decades to best become part of the waves.

“We’re lucky,” Boneck told me. “We’re part of a living surf culture. The originals are still alive. That’s rare.”

He paused for a second.

“I just hope I’m still doing this when I’m Renny’s age.”

Premier Events

Sat, Dec 06

11:00 AM

Goleta

Maker House Holiday Market

Sat, Dec 06

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Selah Dance Collective Presents “Winter Suite”

Fri, Dec 12

5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mosaic Makers Night Market

Fri, Dec 12

7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SB Master Chorale presents “The Light So Shines”

Fri, Dec 05

10:00 AM

SANTA BARBARA

7th Annual ELKS Holiday Bazaar & Bake Sale

Fri, Dec 05

2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Chocolate & Art Workshop (Holiday Themed)

Fri, Dec 05

6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Downtown Holiday Tree Lighting & Block Party

Fri, Dec 05

7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Two Cosmic Talks: Sights & Sounds of Space

Sat, Dec 06

2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Chocolate & Art Workshop (Holiday Themed)

Sun, Dec 07

12:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Chocolate & Art Workshop (Holiday Themed)

Sun, Dec 07

4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Paws For A Cause

Fri, Dec 12

2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Chocolate & Art Workshop (Holiday Themed)

Sat, Dec 13

2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Chocolate & Art Workshop (Holiday Themed)

Sun, Dec 14

12:30 PM

Solvang

CalNAM (California Nature Art Museum) Art Workshop – Block Print Holiday Cards

Sat, Dec 06 11:00 AM

Goleta

Maker House Holiday Market

Sat, Dec 06 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Selah Dance Collective Presents “Winter Suite”

Fri, Dec 12 5:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Mosaic Makers Night Market

Fri, Dec 12 7:00 PM

Santa Barbara

SB Master Chorale presents “The Light So Shines”

Fri, Dec 05 10:00 AM

SANTA BARBARA

7th Annual ELKS Holiday Bazaar & Bake Sale

Fri, Dec 05 2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Chocolate & Art Workshop (Holiday Themed)

Fri, Dec 05 6:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Downtown Holiday Tree Lighting & Block Party

Fri, Dec 05 7:30 PM

Santa Barbara

Two Cosmic Talks: Sights & Sounds of Space

Sat, Dec 06 2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Chocolate & Art Workshop (Holiday Themed)

Sun, Dec 07 12:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Chocolate & Art Workshop (Holiday Themed)

Sun, Dec 07 4:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Paws For A Cause

Fri, Dec 12 2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Chocolate & Art Workshop (Holiday Themed)

Sat, Dec 13 2:00 PM

Santa Barbara

Chocolate & Art Workshop (Holiday Themed)

Sun, Dec 14 12:30 PM

Solvang

You must be logged in to post a comment.