Victor Quijada Keeps Stretching Dance’s Boundaries

Elastic Blast-Off

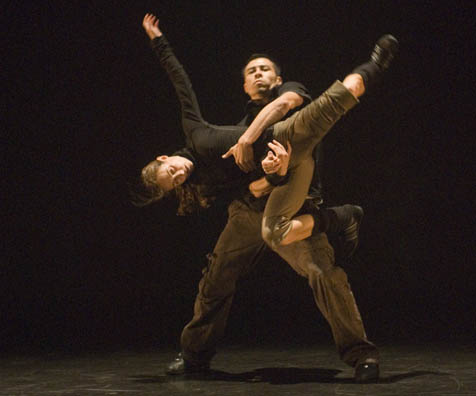

Formed by life in the underground hip-hop culture of Los Angeles, shaped by his work with postmodern dance pioneers, and polished by his time with one of the world’s most respected ballet companies, Victor Quijada fits nobody’s mold. After years of living a double life as a ballet dancer by day and b-boy by night, Quijada finally snapped. Determined to stretch the confines of traditional dance genres, he formed his own company, Rubberbandance Group, in 2002. On Tuesday, February 5, the company brings its high-energy, hybrid dance form to UCSB’s Campbell Hall. I spoke with Quijada by telephone last week.

The show is called Elastic Perspective Redux, and it’s composed of seven pieces, right? Yes, and out of those seven, five are smaller, shorter works that kind of encapsulate the different experiments I was conducting with the group in the early days. This program I feel is really important because it’s milestones in the work we were doing-in this whole blending of styles and asking questions like, “What would happen if we took this energy and put it to that music?”-questions that had been building up in me for a while.

Where did those questions come from? From the time I was seven or eight years old, I was involved in street dances that are a part of hip-hop culture. That’s been a life force I’ve had in me since I was very, very young. When I was 16 or 17, I got introduced to this other world of formal training, of taking classes instead of making up your own stuff. For a long time I kept those worlds very separate. Of course they influenced each other, but even when I was at Les Grands Ballets Canadiens, I was a ballet dancer from 9 a.m. ’til 6 p.m., and then I was in the hip-hop clubs from 10 p.m. ’til 3 a.m. So I kept those worlds very separate, and it was kind of killing me.

So at some point you gave in and started examining the overlap? I started thinking: I hear this classical music, and there’s something in it that I can identify with-this passion, this raw energy blasting at me. If I heard that in my world, this is what I would do to it. But who knows if that would work. How do I re-create the spontaneous energy that happens all over the place in all the hip-hop disciplines-eruptions of creativity-how do I take that phenomenon and represent it onstage, share it with a larger audience? I actually went back to the same underground hip-hop spot in L.A. where I danced when I was younger-it’s really underground; there are amazing, beautiful things going on there that no one else would ever see. I wanted to find a way to bring that to a larger audience.

You started out here in California, but you’ve done a lot of your work in Canada and the U.K. What are some of the differences between working there and working here? Well, it was only a very short time that I was trying to create work in New York. I had finished a three-year contract with [Twyla] Tharp, I had done a contract with Eliot Feld. These are big names in dance. So I was doing the freelance thing, and beginning to show work. But it’s very difficult. Leaving an arts high school in L.A. and going to New York to try to change the world through art-five years later you realize you’re just surviving; there’s no time to change the world. You’re just trying to get part of that crumb that everyone else is trying to get: funding, space, help. In Canada it’s very different. There is a real importance placed on making sure artists are creating, people are seeing and being challenged; it’s part of life. It’s not this weirdo thing on the side. No, this is it; this is what life is about.

You’re how old now-31? How would you say your work has developed since you formed the company in your twenties? I was pretty oblivious. I wasn’t thinking about writing a grant, getting a board of directors. It sounds kind of cheesy, but it’s the hip-hop in me, the passion and energy of that culture where you make something out of nothing. No studio-are you kidding?-it’s right here, right now, in the garage. I wasn’t thinking about anything except that I needed to create work; it came out of necessity.

When I started Rubberbandance Group, I didn’t know anyone who had gone so far into the world of underground hip-hop, and then gone as far as I had into the world of contemporary ballet, and even classical ballet. I had really gone to the depth of those experiences, until they were a part of me. That’s what the group was going to be: a testing ground for whether you could bring dancers from both sides-not just teach them vocabulary and steps, because it’s not about vocabulary and steps-but have them understand the energies.

Did the experiment work? The answer was just enough “yes” not to give up, but all those things I didn’t think about-all of the structure, the funding-those were saying “no.” I wasn’t thinking in that way. There are still those moments of insecurity. We’re still trying to find those dancers who are brave enough just to jump off. Dancers who are classically trained, I’m asking them to do something completely outside their toolbox. B-boys, people who come from this aspect, they don’t have the rigor from the studio, the hours and hours of training, developing your body awareness, your body intelligence. I think that’s it: There’s so much rigor in the work we do, combined with the freedom of the energetic impulse of what I know from the other dances, the other world.

What aspects of your choreography still come directly from that other world of hip-hop culture? It’s hard for me to say. That culture for me is in me. It’s not in the way I wear my hat to the side-it’s not one of my accessories. I am Mexican American, you know? We don’t cross our arms and grab our crotch and say “yo.” What remains, I think, is the way we’re using our bodies. It’s from the cipher.

How would you define the cipher? It’s a group of people formed organically in a circle, who are one by one or two by two entering it and sharing a streaming consciousness of creativity, and pumping and sending energy into the circle. What that does in turn is to create this energetically thick space that you break into and you smash through and rip through and carve and sculpt-this space that is filled with this thick, tactile energy that everyone has been pumping and sending into the space. It’s very visceral, very raw.

The name Rubberband was a nickname given to you by other breakdancers, is that right? Yeah, but I think as I grew out of that it became a metaphor for all these boundaries I was trying to stretch and overlap, all these categories. Everyone wants to categorize things: What is this-is it b-boying, is it ballet? Rubberbandance is about expanding ideas of how to judge things-bundling together different genres, stretching the limits of what we think of one thing or another, stretching the possibilities a little bit.

I thought it was pretty funny that the New York Times called you “post hip-hop,” for lack of a better label. Are you a “post hip-hop” choreographer? I don’t know what I should call it. One of my biggest mentors is Rudy Perez, a Judson Church original member, a big player in the postmodern movement. It makes me think of that. I don’t want to stay stuck or captive to what one definition was. I don’t know if I’m interested in the academic part of it. I know sometimes we need to go there, but I don’t think that’s what I need to do; I need to keep creating, challenging myself not to get stuck, to get too comfortable.

So yes, those experiments worked. They were amazing. When we found these recipes that gave that flavor we said, “Yeah-this does work. Holy moly. Okay, now what’s next?” The works I’ve done since 2002 have been light-years away. The next work I’m doing, I hope to go even further. Every time I finish a work, I’m trying to blast off into another world.

4•1•1 Rubberbandance Group performs Elastic Perspective Redux at UCSB’s Campbell Hall on Tuesday, February 5, at 8 p.m. Call 893-3535 or visit artsandlectures.ucsb.edu. The company will also teach two masterclasses on Sunday, February 3, at Santa Barbara Dance Arts (1 N. Calle Cesar Ch¡vez, Ste. 100). A teen class will be held at 5:30 p.m., and an adult class at 7:30 p.m. To reserve a spot, call 966-6950 or visit sbdancealliance.org.