Father Virgil: A Love Story

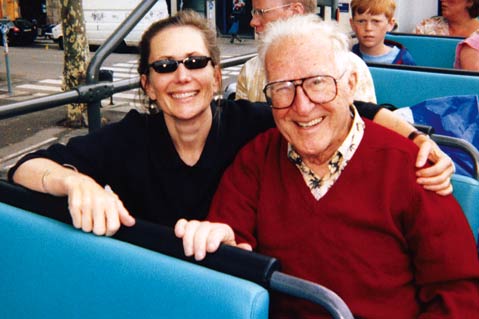

After studying with Father Virgil for years, I came home from the Mission one day and told my husband that I was falling in love with him. I looked forward to seeing Virgil every week. I adored his mind and his heart. I missed him when we were apart. David looked at me and said, “If you are ever going to fall in love with another man, I think an 85-year-old celibate Catholic priest is the perfect choice.”

My story with Father Virgil began in 2001. I had a mystical experience that rocked my world. For a person who did not believe in an intervening God or in miracles, the experience left me reeling and in need of someone to talk to. Through the serendipity of fate, I ended up in the Porters office at the Old Mission. Father Virgil sat with me for an hour as I poured out 25 years of mysticism and the recent experiences that I was grappling with. After a series of questions that included, “Is there mental illness in your family?” and “Are you taking any medication?” he paused, looked at me, and said, “I will be here for you any time of day or night.”

And he was. For seven years. Fr. Virgil met with me once a week. He educated me in mysticism and theology. He helped me understand the essence of monastic vows: to listen, to trust, and to love. He prepared me to take those vows. I was an interfaith celebrant and he was a Catholic priest, but we both delighted in the same God.

When Fr. Virgil died last week, I called The Independent about writing a story. No one had been more of a mentor for me, a father, and a friend. I wanted to honor a remarkable man whom I loved deeply.

In preparing to write this, I talked to many people who knew Fr. Virgil. I discovered I was not the only one with a life-transforming tale about him. What’s really exceptional about my story is that it is not exceptional. Person after person recounted how he had changed their lives. The real love story was not between Fr. Virgil and me. It was between Fr. Virgil and an entire town.

That story started in 1934, when a young boy named George Cordano came to the Santa Barbara Mission. He felt called to become a priest. At 14 years old, against the wishes of his family and the mother he adored, he chose a new life and was given a new name: Virgil.

At first, Virgil struggled through depression and loneliness. His superiors were strict. He missed his family. He longed for the day he would be ordained and someday have a parish of his own. However, instead of being sent into ministry, he was chosen to go on for higher education. His superiors were wise enough to recognize an exceptional mind and they wanted to invest in it. He was devastated, although in the long-run, that education turned out to be a godsend.

Virgil left Santa Barbara for five years of study, the only five years he would spend away from the Mission for the rest of his life. He came back and began a career that is well documented in his biography Padre, which reveals much of the story between Fr. Virgil and the town he adored. It included becoming a professor and a superior at the seminary, being the pastor at the Mission, being an active part of Fiesta, offering Mass for the Poor Clares and the Immaculate Heart Center for Spiritual Renewal, hearing children’s confessions at Marymount, blessing the Harley-Davidson riders, working for Hospice and La Casa de Maria, supporting the Anti-Defamation League, baptizing countless babies and adults, witnessing numerous marriages, and doing what he could to encourage the faith of every single person he met Fr. Virgil became what Harriet Miller called “the heart and soul of Santa Barbara,” meeting all sorts of people, from the Queen of England to the Dalai Lama.

Virgil began each day by reviewing the commitments for that day and dedicating it all to God. He loved to say that God was not only in church, but also at the baseball field, in the bar, and in and through every human interaction and endeavor. He enjoyed talking about politics, sports (he loved baseball), and the Vatican (“If only I could be Pope for five minutes :” he would say). He wrestled with difficult topics. He was deeply upset about the abuse perpetrated by clergy. He advocated dialogue and lamented actions that did not foster healing and reconciliation. He wanted to help those who had been hurt.

Virgil’s love of humanity and divinity led him into a progressive theology. He thought heaven was a state of being, a oneness with love, and it was open to anyone, to an atheist as well as a Catholic, a Muslim, a Hindu, a Buddhist, or a Jew. “If you have an exclusive God,” he would say, “you have a false God.”

“Perhaps it is more important to Jesus that all people be saved than that all people be saved through him.” That theology excited Virgil. He valued love and inclusion over all other ethical considerations. He believed there should be married clergy and female clergy. He believed in accountability, and also in acceptance and forgiveness. “If you think God is a judgmental God, you are not allowing God to be God,” he would say. “God is love. Love doesn’t judge.”

Rabbi Arthur Gross-Schaefer called him “A Man for All Religions.” He said, “Fr. Virgil had a sensitivity that reached out to all religious groups. He radiated compassion, respect, and safety for everyone. He could have a strong opinion, but he also created the space for others to disagree.”

“All of life comes down to dealing with our differences,” Fr. Virgil would say. “We cannot just tolerate our differences. We need to celebrate them. We have to empower the other to be other.” Those thoughts are echoed by the rabbi, who said, “Fr. Virgil championed the idea of the big tent, a place where everyone could worship, where there was room for all.”

Fr. Virgil was remarkable in countless ways, but he was also quite human. He struggled with being judgmental, especially of people he considered spiritually undereducated. He could be stubborn and intolerant, especially of intolerance. The people he most admired were simple, kind, and generous, people who were “heart-centered.” He found it difficult at times to be emotionally open. He came into his heart through the side door of his mind.

The evolution of both Virgil’s mind and heart during his 89 years is inspirational. He was an extremely methodical thinker. He would often say “wait a minute, wait a minute :” as he took the time to process what someone said. He didn’t rush to make a decision. He thought through the steps logically and carefully, and was deeply circumspect. During the course of his life, he became a radical, but he was always a cautious radical.

Steve Jacobsen, a Presbyterian minister, recalled how wonderful it was to have Fr. Virgil offer the Eucharist with him at his church. Jacobsen said that one of the many things he admired about Virgil was that he didn’t believe that our differences should get in the way of loving each other. Lois Capps remembered when her husband Walter would bring his religious studies students to the Mission to meet Virgil. “The students were taken by his openness,” she said. “Father Virgil was Santa Barbara’s padre. People flocked to him. He reminded them of what was important in life.”

Athena Roebuck remembered when she lost her three-year-old child, Renee, to leukemia. Virgil was there when her daughter took her last breath. Athena and her family remain deeply grateful for everything he did. Alice MacDonald went back to study theology because Virgil encouraged her. He thought a rigorous education would support her deepening faith. He was there with the rest of her family at her graduation from Loyola Marymount, cheering her on. The children at Marymount delighted in Fr. Virgil’s kindness and humor. They came to him to confess sins like “I was mean to my brother last week,” to which Virgil might reply, “Sometimes I was, too.”

Lois Capps summed it up beautifully when she said, “You didn’t have to take a test to be Fr. Virgil’s friend. He was just so open to people.”

On April 24, 2007, the night before my 50th birthday, Virgil was rushed to the emergency room. I had invited him to my party, but since I knew he hadn’t been feeling well, I wasn’t surprised when he didn’t show up. I was, however, profoundly surprised by the four phone messages I listened to after everyone had left. “I’m so sorry I’m not there,” he said, calling from the ER, “but I almost died last night.”

He had arrived at the hospital with a 107-degree temperature. The doctors were amazed that he was coherent. They told him he was dying, unless he wanted “heroic measures,” which they weren’t necessarily recommending. Virgil went into prayer. He saw Fr. Junipero Serra. Fr. Serra had been willing to do a lot of work. Virgil felt God needed him to work hard as well. He opened his eyes. “Do whatever it takes,” he told the doctors. Fr. Virgil later woke up to the words: “It’s a miracle.”

In the year of life that that recovery bought him, Fr. Virgil did many things. He fought through his ill health like the best of warriors. Because the Mission no longer has an infirmary, he was moved to Vista del Monte. He mentioned that he deeply missed morning prayers and his life at the Mission. I offered to take him to prayers, but he replied without hesitation: “Wherever I am is my Mission.” He began to offer mass and classes on spirituality at Vista del Monte. But then his health took a turn for the worse. He was diagnosed with esophageal cancer. Once he realized he did not have the strength to fight it, he quickly shifted into preparing to surrender his life.

I asked him if he had any fears about death. He looked at me with tears in his eyes. “I only hope I can surrender fully,” he said.

We talked about his funeral. He wanted to be sure it was said that he received more than he gave. He cried many tears of gratitude for the life he lived, for his faith, for his Franciscan brothers, for his family, and for his friends in Santa Barbara. (His “5,000 best friends,” as one friend commented.)

Fr. Richard bent over Virgil as he lay dying. “You have spent your life in service of a very large God,” he said. “Now you are going into the arms of that God.”

Fr. Virgil Cordano died on Thursday evening, surrounded by people who loved him. Fr. Richard said a prayer and, when Virgil took his last breath, the people there burst into spontaneous applause. He had lived his life well, and, in the moment of his last breath, he became one with “the Love that is eternity.”

I am deeply sad that he is gone, that I cannot call him, that he will not argue theology with me any more or delight in our shared faith. But far more than I am sad, I am grateful. He taught me to have a “spirituality for all of reality.” He taught me to meet people where they are, not where I would like them to be. He taught me that it was possible to be passionately connected to a religion and at the same time to be able to transcend it. “Theology can divide us,” he said. “Spirituality unites us.” The unifying spirituality of love is where he and I met. It is where he sought to meet every person, and it is the legacy he leaves to Santa Barbara.

Fr. Virgil’s funeral will be held outside at the Mission. He once mused, “Maybe God is happier seeing people gather outside the church than in it.” Maybe Virgil said that because we can all fit there, out in the open, where there are no walls.

This year at I Madonnari, the featured artists did a piece with seven angels. When Fr. Virgil died, they added a depiction of his face with that wide, inviting smile. Seeing that smile takes me back to a time many years ago when he and I were leaving the Mission. He saw the chalk painters, threw up his hands, and beamed. With the purest joy he exclaimed, “Oh, look! Just look!” I imagine him saying that now.