Clouds Gathering Over Police Chief

Budget Showdown, Mayoral Face-Off Confront Cam Sanchez

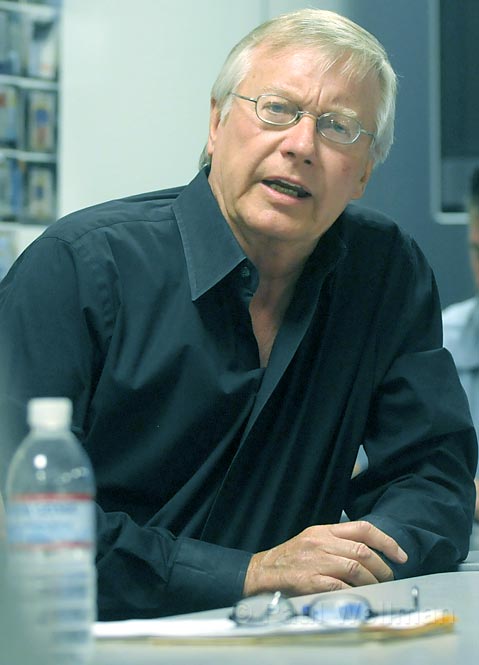

It’s a little premature to declare that the proverbial perfect storm is brewing over the head of Santa Barbara Police Chief Cam Sanchez, now entering his eighth year at the helm of the city police department. But the clouds definitely are gathering, and they show only few signs of blowing away.

Two months ago, for example, a Santa Barbara jury concluded it simply did not believe the chief of police when Sanchez accused Wayne Scoles, a burly, hot-tempered Mesa activist, of calling him “a Mexican motherfucker” last June before Scoles allegedly threatened to “kick his [Sanchez’s] ass.” Scoles, who was arrested and prosecuted on misdemeanor charges, denied threatening the chief or making racist remarks; Sanchez was the key witness against him. As courtroom melodramas go, the Scoles hearing was inconsequential in the extreme. But for the chief, it clearly was an embarrassment.

More recently, Chief Sanchez found himself forced to apologize to a prominent Latina anti-gang activist, who had been dragged out of her car at gunpoint by law enforcement officials during the erroneous execution of a search warrant on suspected drug dealers. Even though county Sheriff’s deputies were to blame-they had the wrong house on the wrong street-Sanchez was brought in to limit the fallout. If city police are to find success against gangs, they need active help from low-income and Latino residents, many of whom regard law enforcement with considerable fear and suspicion. The public takedown of a well-known activist did little to allay such concerns.

In between, Sanchez found himself the target of an orchestrated mini-insurrection conducted by the Fire and Police Commission, usually one of the quietest and most quiescent of all the city boards and commissions. Typically, Fire and Police Commission meetings last 30 minutes; this one in March went two hours. Anyone with a gripe against the chief was invited to show up. Scoles was the first to speak, demanding the chief’s resignation. He was followed by Jim Worthen, a former Republican Party operative and public access talk-show host, who likewise wanted Sanchez deep-sixed, for allegedly failing to return any of numerous phone calls placed by Worthen.

If that weren’t enough, a homeless advocate denounced the department’s decision to close the murder investigation on Ross Stiles, a homeless man who died under suspicious circumstances. The department’s investigation was trashed as half-hearted at best. “Homelessness is not a capital offense,” the activist said in a written statement.

Sanchez was not present at the commission meeting, instead attending funeral services for the four Oakland police officers who were killed in the line of duty last month. He was also attending the funeral for a close personal friend in Hollister. Upon his return, Sanchez would comment of Worthen’s attack, “I never even heard of the man.” At the same hearing, downtown hotel owners decried the noise and public debauchery taking place in the city’s “Entertainment District.” One commissioner, Thomas Parker-a former FBI agent and now a private security consultant helping corporations deal with white-collar crime-said he was shocked at how low the police profile was in the drunk-and-disorderly zone. During one 90-minute Saturday-night tour, Parker said one bar he visited “looked like gang central,” he entered another where a male strip show was unfolding, and, in all that time, he saw only one police car cruise by.

In years past, the commission busied itself primarily with dance permits and city towing contracts. But with the recent appointment of Parker, new to Santa Barbara this year, a majority of the commissioners are now inclined to take a more robust interpretation of their duties and functions. The commissioners now want to comment meaningfully on a wide array of issues, like gangs and proposed budget cuts. To this end, they regard Sanchez as an obstacle and an impediment. If there’s a confrontation brewing, they show little signs of backing down.

Typically, big-city police chiefs wear out their welcome professionally after about three years. For smaller-market law enforcement executives, the life expectancy is closer to five. By this measure, Sanchez has been a screaming success. And in a field where no news is good news, he has succeeded in maintaining a notably low profile throughout most of his tenure in Santa Barbara. Perhaps that’s why the recent eruption of controversy seems so striking. But then, money woes have a nasty habit of highlighting controversies that would otherwise lay dormant. Though there’s definitely more static on the chief’s line than the public is accustomed to, it’s hardly enough to threaten his job. Even so, with 30 years of law enforcement under his belt, and 16 as a chief, Sanchez will soon be able to walk away from the post and enjoy the enviable retirement benefits reserved for those in law enforcement. For the time being, however, Sanchez is staying put, doing his best to adopt a philosophical attitude to the slings and arrows coming his way.

Money, Honey

It appeared the real push would come to shove this week with the much-anticipated release of the city’s new budget plan. No department was to be spared the fiscal ax, and City Administrator Jim Armstrong had ordered the police department to identify at least $1.3 million in “adjustments.” That’s roughly 4 percent of the department’s budget. By contrast, non-public safety departments -like Parks & Recreation-were told to cut closer to 10 percent.

“There are no sacred cows,” Sanchez said in a recent interview. “We all have to share the pain.” Initially, it appeared that pain would involve the elimination of five positions of sworn officers-currently now vacant-and the positions of eight non-sworn officers, currently now filled.

And to the politically influential Police Officers Association (POA), that was both wrong-headed and dangerous. The union’s members were geared up for a showdown of epic proportions to fight off budget cuts. As they told it, the police department has been bleeding for the past nine years, losing positions and funding at the expense of officer safety and public safety. At its height, the department was authorized for 150 sworn officers, but that was thanks to federal grants bestowed during the largesse of the Clinton administration. Four years ago, it was down to 126. Now it’s authorized for 140. But in the flesh, the real number is closer to 134, with three police-academy graduates on the way and several others on injured reserves.

The POA’s initial reaction to the proposed budget cuts was to launch a lobbying blitz, quietly educating the City Council what would happen to public safety if five sworn officers and eight non-sworn were to be sliced or diced. Sergeant Charles McChesney, the POA’s president, said he could identify only $30,000 in cuts that would not impact public safety. Rather than inflict such cuts, McChesney said City Hall should liquidate some of its $175 million investment portfolio. To date, no city employees’ union has ever targeted the investment portfolio before. This was a first. City finance czar Robert Peirson insisted that such a move would be impossible and illegal, arguing that the bulk of the city’s investments are controlled by what are known as “enterprise funds,” such as the municipal golf course, water district, airport, or waterfront.

Of all the major unions representing city employees, the POA remains the only one to have officially declined to discuss contract “give-backs” in the face of looming budget shortfalls. The Service Employees International Union Local 620 currently is negotiating a host of major concessions-raise freezes, work furloughs, and no vacation-time cash-outs-in exchange for a no-layoff commitment. The firefighters’ union has not formally entered into such negotiations, but has met informally with city negotiators and expressed openness to discussing such measures.

What promised to become a bare-knuckled budget brawl has been either postponed or solved-time will tell which it is-by a combination of wishful thinking, creative bookkeeping, and/or shrewd grant writing. That’s because City Administrator Armstrong decided to assume that City Hall will be awarded a major grant-part of the federal government’s economic stimulus program-that would fund as many as five officers’ positions for the next three years. City Hall has only just submitted the grant application and won’t know its fate until the middle of the summer. Armstrong said City Hall’s chances are “very competitive,” and noted that in years past, the city has done well with such grants. In addition, he said City Hall recently won a $230,000 grant that will help fund positions in the police department for the next year and a half.

If City Hall wins those grants, the problem is solved. But if it falls short, the road ahead promises to be bumpy indeed. If the excruciatingly bitter contract negotiations that took place three years ago between City Hall and the POA provide any illumination-after which City Hall agreed to a 26.5 percent increase in pay and benefits during three-and-a-half years-such a budget battle could prove especially disruptive, painful, and publicly contentious.

Among city employee unions, the POA has always carried the biggest stick. Its endorsement alone imbues a candidate with a law-and-order respectability. But that’s just the beginning. The union donates generously to the candidates themselves and runs its own separate campaigns on behalf of its candidates. In addition, POA members walk precincts on behalf of their endorsees.

This year, the union has a lot at stake. Most immediately, there are the budget cuts. But this December, the POA contract expires; negotiations for a new contract are slated to begin sometime this summer. The starting wage for an entry-level cop is $65,000 per year without overtime. But with overtime and seniority, 55 of the 101 sworn officers are earning $100,000 or more. That puts them on par with officers in comparable departments from Santa Monica to Santa Barbara.

Between now and November, Santa Barbara voters will select a new mayor and three new councilmembers-in other words, a whole new council majority. Already, the union has endorsed Councilmember Iya Falcone in her bid to become the city’s next mayor. Falcone is so highly regarded by the POA that the union didn’t extend to Falcone’s chief rival-Councilmember Helene Schneider-the customary courtesy of an endorsement interview. Although the mayoral campaign remains in its early stages, the looming budget cuts have already emerged as a divisive issue. Falcone initially voiced strong support for maintaining the status quo of troop strength at 140, but at a gathering of West Beach merchants and residents on Monday evening, pledged her support to increasing patrol strength to 150. Schneider, who in the past has been supported by the Service Employees International Union Local 620, has suggested the department could save $550,000 with no loss of service if the POA agreed to waive a scheduled pay increase and forgo vacation cash-outs.

Crossfire

Giving dangerous urgency to this sprawling debate is the growing public impatience with the persistence of gang violence. While the number of gang-related incidents is holding roughly steady, the brazenness of the participants has been increasing. And so too has the amount of front-page news space devoted to mug shots of intimidating gang members, whether real or merely alleged.

Barring the miraculous intervention of these federal funds, Chief Sanchez will find himself caught in a furious crossfire between his officers’ union and his immediate boss, City Administrator Armstrong, the one man in City Hall the POA most virulently distrusts. (Privately, some union leaders believe Armstrong would like to reduce the number of sworn officers on the payroll to 130, while they contend a city of Santa Barbara’s size and complexity should ideally have as many as 150. Armstrong denies ever voicing any opinion at all regarding the proper size of the police department.)

In fact, the union has already alerted Sanchez that it is contemplating a campaign to amend the city charter to make the police chief directly answerable to the City Council, not the city administrator. Sanchez, for the record, opposes such a change, arguing that that would politicize the post, that Armstrong is “a great boss,” and that he already enjoys unfettered access to all councilmembers and they with him. “At the end of the day, most people don’t care who I answer to,” he said. “All they want to know is that a uniform shows up at their door when they call for service.”

For his part, Sanchez takes pains to project abiding optimism in the face of multiple grim realities. He shrugged off the Scoles verdict, saying, “We have a jury system in this country, and the jury has spoken. The whole thing was unfortunate.” He praised members of the Fire and Police Commission, but disputed assertions by some that he’s tried to keep them in the dark about the budget’s impacts on the department. “That’s absolutely untrue,” he declared. If the commissioners wanted to expand their inquiry into gangs beyond what the department already provides, he said it would be up to them to take the initiative. “If they want to go out into the community, they can,” he said. “But it would be silly for us to go get people.” And he emphatically denied allegations by some commissioners that he refused to appear at any commission meetings attended by members of the POA. “I would never insult my association by saying I wouldn’t be there,” he stated. “The more the merrier.”

As for the coming city elections, Sanchez commented, “Two things I don’t worry about: I don’t worry about any mayor’s race or any City Council elections. I get along with all the candidates and they all have the city’s best interest at heart.”

Sanchez’s relationship with his union has always been a dicey mix of cordiality and friction, regard and suspicion. He was the union’s first choice of candidates, but he was hired from outside the department. Almost immediately upon taking the post, Sanchez inherited a messy sex-discrimination lawsuit filed by two female officers who contended they would have been promoted to sergeant-a post that at that time no woman officer had ever achieved-were it not for the department’s good-old-boy system. The POA, they charged, was part and parcel of that club. The jury awarded the two women $1.8 million.

The grumble on Sanchez always has been that he’s not enough of a cop’s cop, that he’s distracted by functions outside the department, and that he’s not hands-on enough. Much of the day-to-day responsibility of running the department was delegated largely to Rich Glaus, former assistant chief. And the POA has always been quick to complain Sanchez doesn’t stick out his neck enough for his officers.

However, Sanchez has no shortage of champions. His support for community-oriented policing jibed well with the City Council’s liberal-leaning, Democratic-dominated majority. On gang issues, Sanchez’s Latino heritage helped diffuse concerns about racial profiling. “Do I ethnically profile? You bet I do. One hundred percent of the victims of these gangs are Latino,” he said. “100 percent.”

In action, Sanchez and his department have provided a mix of an iron fist and a velvet glove. Last week, for example, the department was commended by a statewide law enforcement agency for Operation Gator Roll, in which more than 200 suspected Eastside gang members were arrested by a force of 400 federal, state, and local law enforcement officials directed by city police last October.

But Sanchez considers “the best day” of his 30-year law enforcement career the time he spent last summer engaged in heart-to-heart discussions with gang bangers then serving time at Los Prietos Boys Camp. Two of those gang members have since enrolled in City College, found jobs, and appear to be on their way out of gang life. Sanchez challenged members of UCSB’s Latino Business Association to mentor at-risk teens. The group responded by providing about 35 mentors for Santa Barbara High School students, meeting once a week for at least an hour. The hope is to show there are alternatives to the bloody turf battles between Eastsiders and Westsiders.

Getting Along

More recently, Sanchez has taken back some of the ministerial functions he’d delegated, such as promotions. Not only was the first female officer promoted to sergeant under his watch, but two more have also been promoted since then. Many Latinos have moved up the promotional ladder as well, infusing the department with greater diversity at all levels. Due to a wave of retirements, Sanchez appointed a whole new command staff this January, replacing Deputy Chief Glaus with Frank Mannix. His three new captains are Alex Altavilla, Armando Martel, and Gilbert Torres.

Where the union is concerned, Sanchez has said his door is always open. Likewise, he feels free to speak his mind to McChesney or former POA president Mike McGrew, if need be. How often that actually occurs, however, is unclear. McChesney, who was elected in October 2007, said he’s sat down over coffee with the chief just once.

McChesney said he understands Sanchez answers to City Administrator Armstrong. But he would prefer if Sanchez had voiced more concerns regarding some of the proposed cuts. Outgoing Fire Chief Ron Prince held his nose a little when discussing the $750,000 his department was slated to endure. Prince made it emphatically clear he was not personally recommending these cuts, merely identifying them, as ordered by Armstrong.

Much to the union’s chagrin, that’s not how Sanchez played it during negotiations three years ago. And it’s not how Sanchez is playing it now.

When it appeared the positions of five sworn officers would be stripped from his department, Sanchez argued it could be done safely. Those positions would be filled by cops working the Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) patrol, staffing the Police Activities League (PAL) program, and two of the beat coordinators. By reassigning, he said, the department’s essential patrol strength would be maintained at about 50. “In terms of calls for service, that won’t suffer,” he said. “Other things will suffer, but my number-one goal is to keep police officers in police cars. Some programs will have to be suspended to keep cops in cars, and that’s unfortunate. But when people pick up the phone and they want a cop, they’re getting a cop.”

Whether or not the department secures major new grant funding, the public will be paying more for its services. By increasing the price of a parking ticket by $4, the department estimates it can raise $300,000. People who have their cars towed will see tow-release tickets soar by 250 percent.

POA President McChesney expressed satisfaction that the department appears to have dodged a budget bullet. But some of the cuts, he said, will still sting. He said burglaries have increased by 25 percent compared to the same time period last year. But with one less crime-scene technician out of a two-person team, it will take that much longer to get fingerprints processed. Animal control officers, he said, don’t just respond to wildlife incursions or dangerous dogs on the prowl. “They’re an integral part of our anti-gang unit,” he said, noting that many gang members have pit bulls. “This will have a very real impact on public safety.”

Ultimately, it will be up to the City Council, not the POA, not Jim Armstrong, and not Cam Sanchez, to hash out a workable budget. That will play out in the weeks and months to come. Given the impending election and the stakes involved, all of the proceedings will be intensely politicized. In the meantime, Sanchez denied rumors that he’s angling for a new job as chief of Oakland or San Francisco. He has not applied, he said, nor has he been invited to do so.

The friend whose funeral Sanchez recently attended in Hollister -where Sanchez used to be chief-died of cancer before turning 60. “You know, I’ve been a cop for nearly 30 years and a chief for 16. I know we’re going through hard times economically, and it’s nobody’s fault at the city or the county. It is what it is and we’re all going to have to make some sacrifices,” he said. “But let me tell you something, I don’t have any problems. I’ve got nothing to complain about. Nothing at all.”