An Idiot’s Guide to the Common Core

California Schools Adopt New Standards

This school year, teachers will begin to implement the most significant changes to classroom instruction since California first adopted standards in 1998. Along with 45 other states, three territories, and Washington, D.C., the Golden State is betting its kids’ futures on new guidelines called the Common Core State Standards. This new touchstone is largely the result of pressure from the federal government, which told states they would be ineligible for Race to the Top funds if they did not adopt internationally vetted standards. (Ironically, California will not be eligible in the near future anyway because both the governor and the California Teachers Association refuse to adopt statewide teacher evaluations based on standardized test scores.)

Common Core does not dictate curricula, but it sets goals for K-12 classrooms that emphasize depth over breadth. The new standards are supposed to be fully implemented by 2015, but that means teachers have to start adapting now, by running pilot programs and experimenting with new lesson plans throughout this school year. Leading the charge are people like longtime La Cumbre Junior High math teacher Janet Hollister, who is now a “teacher on special assignment,” responsible for preparing her colleagues for the changes to come. The Santa Barbara Independent interviewed her and other South Coast educators in a quest to figure out what Common Core means in the most concrete terms.

to solve a problem and think about somebody else’s point of view.’ — Janet Hollister (pictured), teacher on special assignment

How It Works

Common Core is the culmination of work done by two nationwide groups, the National Governors Association and the Council of Chief State School Officers, which were tasked with evaluating why American schoolkids were falling behind on global education benchmarks as well as college- and career-readiness. They found that teachers were racing through textbooks and checking off boxes without pausing to gauge the intellectual growth of their students, so Common Core aims to correct that by requiring fewer topics but allowing students to think more deeply. It also makes the teacher less of an authority figure in the classroom, forcing students to spend more time figuring things out themselves.

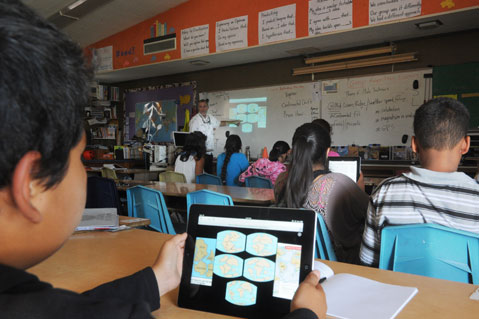

To an outsider, that may make a Common Core classroom look “chaotic,” admitted Natalie Ireland, another teacher on special assignment who, until now, worked at Franklin Elementary. With the new standards, kids will be leading the inquiry and working collaboratively on projects — not sitting quietly at their desks listening to a teacher lecture at the front of the room. But Ireland is excited about it, explaining, “I think school will be fun again.”

At first, Common Core will affect math and English, but new science standards are in the pipeline, as well. In English, students can expect to see a greater ratio of nonfiction to literary texts, said former San Marcos High School teacher and current UCSB professor Tim Dewar, but that doesn’t mean literature will go by the wayside. Literary texts may be read in conjunction with historical documents, for instance, and there will be more emphasis on students reading and writing in other subjects. “If the only place students are reading and writing is in English,” said Dewar, “then we are screwed.”

In high school math, traditional subjects like algebra, geometry, and trigonometry will be more integrated to emphasize their connections, and more statistics will be required as it is deemed more useful in the working world. Santa Barbara district teachers even favor abolishing the traditional ordering and naming of math courses to replace them simply with Math 1, 2, and 3, a change that will be voted on soon.

Altogether, Common Core proponents hope to foster real-world problem-solving skills. “How many people in their forties are still factoring polynomials?” asked Chris Ograin, a math and education professor at UCSB. “We want to have people who, when they encounter a problem in the workplace or wherever, can engage with that problem.” So in the classroom, students will be asked to struggle more to find solutions, a process that requires a healthy dose of metacognition.

Why It Works

A fancy way of saying “thinking about thinking,” metacognition is what happens when students are asked not just for the right answers but how they got to those answers. Vieja Valley teacher Allison Heiduk, also a Common Core fan, explained that currently, when instructors teach texts, they focus on comprehension. Previously, while teaching a book called Frindle, she might have asked her kids, “What did Nick do to transform the classroom into a tropical setting?” Under the new standards, she might instead ask, “What do you think Nick’s motives are? To cause trouble? Is there an educational reason? What is your evidence?” The goal is to always drive students back to the text and encourage them to formulate evidence-based reasoning — in short, a bit more “why” instead of just “what.”

The hope is for better communication skills in all subjects. “Students are going to have to think about multiple ways to solve a problem,” said Hollister of La Cumbre, “and think about how to explain how to solve a problem and think about somebody else’s point of view.” The process of finding an answer and defending that answer should be just as important as the answer itself.

Students who excel under the current system may be most frustrated with the Common Core, said several teachers, explaining that those who are good at following directions, finishing work quickly, and finding right answers will be forced to consider other answers and to articulate their thought process. But Common Core will encourage critical thinking, which is important to teachers like Ireland because currently, she said, “We are graduating kids who aren’t good problem solvers.”

Promise of Perserverance

A key trait of good problem-solving is perseverance. As it is, teachers, especially in math, focus on process. They often show students the steps — via a blackboard or projector — to solving a particular type of problem. Common Core lesson plans will ask students to formulate the steps themselves.

Here’s an example of a lesson plan from Carla Abatie, a math specialist who works for UCSB’s education program: Students are told that they receive a cardboard crate of oranges stacked in two layers of 12 like this: 2 × 2 × 6. They are asked if they can arrange the oranges in a configuration that will use less material, which forces them to explore concepts like volume, surface area, and factoring. What they should figure out is that the closer to a cube they get, the more efficient the shipment. That’s the answer, but it’s something the teacher never tells them.

Along with struggle and perseverance, Common Core adds rigor. For years, Ireland has taught a book called Yellow Star, about the Holocaust, to her 4th graders, reading the book out loud and leading her students through the plot. After being trained in an instructional method called Lemaster (after its inventor), she assigned her students articles about the Holocaust for context and asked them to take their own two-column notes. Now, to meet the Common Core expectations, she might have them choose their own research topics, find secondary research materials on their own, and then create PowerPoint slideshows to present to the class. Yes, for 4th graders.

Minding the Gap

Decried as a federal takeover of education by detractors who complain the standards weren’t fully vetted and worry that the transition is happening too quickly, Common Core is not heavily criticized on its merits. But there are some real concerns, one having to do specifically with the rigor of the new standards and who will struggle most with them.

Right now, poor minority children fare far worse in school than kids from white middle- and upper-class backgrounds. Class-based achievement gaps exist in most countries, but the U.S. is the most stratified. In fact, a recent Stanford study that analyzed the oft-cited international ranking of industrialized nations in which the U.S. came in 14th in reading and 25th in math found that the U.S. reported a higher percentage of poor and ill-educated children than its peer nations. Adjusted accordingly, the study showed, the U.S. would actually rank fifth in reading and 10th in math.

Some worry that Common Core may actually increase this gap, reinforcing the advantages of the haves while exacerbating the challenges to the have-nots. Santa Barbara teachers are sensitive to the issue, especially for putting more reading and writing tasks upon English-language learners, but they remain bullish on the new standards. Hollister thinks Common Core may actually help shrink the gap. “When we start racing through texts, that’s when parents hire tutors,” she said. “Then you have a socioeconomic gap opening up.”

Testing to Come

While teachers relish standards that let them dive deep into their subjects, Common Core also demands concrete results via enhanced standardized testing. With testing comes stakes — for school reputations, for funding, maybe even one day for teacher evaluations — and if the early-adopter examples of New York and Kentucky are to be heeded, we can expect a precipitous drop in proficiency rates early on.

Parents have been asked to be patient during the transition, and California won’t institute new “Smarter Balanced Assessment” tests — which will be given to grades 3 to 8 and 11 — until the 2014-2015 school year. (This school year, students are expected to take the same old STAR exams, but the state applied for a waiver from the federal government, arguing that they are now pointless.) The new tests will be given on computers, which will use “adaptive technology” to increase or decrease the complexity of questions based on a student’s previous answer. The theory, also employed in the modern GRE taken by hopeful grad students, is that this method better tests what students know rather than what they don’t. (Try them for yourself at www.smarterbalanced.org/pilot-test — they’re quite demanding!) But the new testing protocols also mean that schools will need to figure out how to get an electronic device in the hands of every single student.

Clearly, there is no shortage of challenges to be faced by California classrooms in the years to come. At a recent back-to-school meeting with the media, Santa Barbara schools superintendent David Cash admitted that teachers have an “uneven knowledge” of the new standards and explained that they will be cramming for the next couple of years. With the year’s first school bell about to ring, it looks like the learning curve of Common Core may be just as steep for teachers as it will be for students.